I'm making a presentation about my masters thesis this week at a graduate symposium at York University. Below is the basis for what my thesis will be when I finish my research and start writing it in December. I've already written a bit about this subject, but this is the longest and most organized piece I've done about it to date. I know that the things I'm writing about vary based on time period, studio, director, etc. but fundamentally, there's far more collaboration in an animated performance than in a live action one. Whether you agree or disagree, feel free to leave comments.My name is Mark Mayerson. I’m in the studies stream and I’m doing a thesis on the collaborative nature of animated acting. My professional experience has been as an animator, as well as writing and directing for animation. I’m currently teaching animation at Sheridan College.

Within animation, there’s a cliché that an animator is an actor with a pencil. That makes it sound like a there’s one to one correlation. Animators are just like actors; they just use different tools. My experience is that animators are significantly different from actors in terms of how animated film production is structured, and my thesis is an examination of how and why this is the case.

In live action, we think of the actor as being central to a role. Marlon Brando is Vito Corleone in

The Godfather. We understand that the script, direction, lighting, costuming, etc. all contribute to the performance, but while we can’t quantify how much Brando contributes, we have a gut feeling that he is responsible for the majority of the performance. Replace him with another actor and the role is different. It’s Brando’s body, voice and movement whenever the character of Vito Corleone is on screen and most of all it’s Brando’s brain driving it all.

In other cases, such as the James Bond films, we can easily see how changing the actor affects the role. Sean Connery is different than Roger Moore, Pierce Brosnan, etc. If you use the TV series

Bewitched as an example, two different actors, Dick York and Dick Sargent, both played the role of Darren Stephens yet nobody confused them. They were different in same the part.

Imagine watching a dubbed film. The on-screen actor has acted the role in the usual way. The voice actor, adding his or her voice after the visuals have been created, is constrained in several ways. The timing and the emotions are dictated by what’s on the screen. The voice actor has to work within the limitations of the visuals if the dubbing is going to be successful.

If the dubbed version is the only version available to you, how do you judge the success of the performance? If the voice work is poor, is it due to the voice actor or the constraints placed on him or her? If the acting is successful, how much is due to the on-screen actor and how much is due to the voice actor? Who is responsible for the performance?

Animators are in this situation but in reverse. Where dubbing takes place after live action has been filmed, in animation the creation of the motion takes place after the voice tracks have been recorded. A performance is split between two collaborators who may never meet. Where the voice actor gets to interpret the script, the animator is forced to interpret the voice actor. Failing to do so results in a disjointed result on the screen.

This is only the tip of the iceberg for the ways that animated performances are fragmented. I’ve got to go into some history here.

Initially, animated films were the work of single artists. Winsor McCay, J. Stuart Blackton and Emile Cohl were among the earliest animators and they did all the important work themselves. Of the three, McCay was the one most interested in acting. In his

Gertie the Dinosaur of 1913, he animated the dinosaur by himself. We can say that McCay is Gertie the same way that Brando is Vito Corleone.

Beginning around 1913, animation studios sprang up to produce series of films based on continuing characters such as Mutt and Jeff. This is where fragmentation entered the process. An animator who worked on the Mutt and Jeff cartoons recalled that they would pick a setting, like the beach, and then each animator would grab a section. By verbal agreement, one animator would deal with gags about a shark and another animator would deal with gags about mermaids. Each animator was responsible for writing his own section, drawing the background art and designing any characters he introduced in the segment.

At this point in animation history, cartoons were mostly about gags and acting wasn’t even on the radar. In a single cartoon, four or five animators would each take turns playing the roles of Mutt and Jeff. They wouldn’t see each other’s work until it was shot and cut together, so creating a coherent performance was not going to happen.

Animated acting came into its own in the 1930’s at Disney. The paradox is that Disney accomplished this by increasing the amount of collaboration rather than reducing it. The difference was that the control was centralized in Disney’s own hands. He used separate artists to design characters, to draw storyboards, to animate the characters and to re-draw the characters “on model” for the final frames of the film. Directors and musicians would plan out the tempo of every scene and voice actors would perform the dialogue prior to animation.

Every step of this process contributs to the performance. Character designers create the look of a character specifically to evoke a particular response from the audience, so animators, unlike actors, are forced to come to terms with an unfamiliar appearance that they don’t control.

(Powerpoint slide of early and final Queen designs from

Snow White here. In live action terms, it’s the difference between Rosanne Barr and Angelina Jolie. Or in historical terms relative to Snow White, Margaret Dumont and Gale Sondergaard.)

Where a live actor can take his or her body for granted and is confident about how it moves, an animator never knows what age, size, shape or species will need to be animated in the next scene. In live action terms, it’s as if actors had their brains transplanted into different bodies. John Wayne becomes Don Knotts and Don Knotts becomes Marilyn Monroe.

In animation, it’s more severe. Several animators get their brains transplanted into a single body, and they have to grapple with how that body is going to move and how they’re going to create a consistent performance.

In live action, storyboards are mainly used for shot composition and continuity. In animation, because of the low shooting ratio, storyboards concern themselves with acting. On a feature film, an animator may produce as little as 5 seconds a week. In TV, the animator will probably produce between thirty seconds and a minute a week. At that rate, revisions take far longer than doing another take on a live action set. A production has to clearly communicate the emotional progression of each scene to the animators to enable them to get it right (or close to right) on the first attempt. But that means that the conception of the performance (both audio and visual) exists before the animator starts work.

(Story reel/Animation comparison from

Mulan here).

In many ways, the job of the animator is more a synthesizer than a creator. All the work done prior to animation must be woven together into a coherent whole. This is different than an actor being free to create an interpretation with the approval of the director.

When an animator’s work is finished, there are still hands that shape it before it reaches the screen. At Disney, animators were encouraged to concentrate on performance more than drawing. Their assistants took their rough drawings and polished them into what finally appeared on screen. Assistants also often took care of secondary bits of animation on the character, such as hair, drapery, or costume details. (Slide of

Sleeping Beauty rough and clean-up here.) Their contributions aim to be invisible, but there is the potential for introducing problems. In the 1939 animated feature

Gulliver’s Travels, there are scenes of the Princess Glory character where the assistant work detracts from the animation. The character’s hair shifts around on her head, giving the impression of a loose wig. (Princess Glory clip here.)

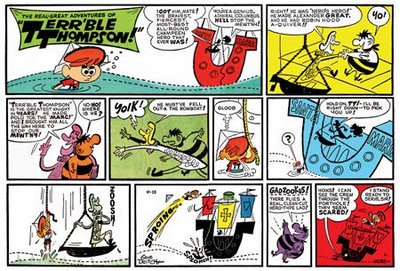

The problem I’m dealing with is determining where an animated performance is centered. In the case of a character like Bugs Bunny, he had at least three character designers, nine directors, eight writers, one voice actor and more than two dozen animators in a fifteen year period. Is there anybody whose influence is as large as Brando’s on Don Corleone?

In feature films, animators are sometimes cast by character, but the amount of screen time a character has often requires that the animator supervise other animators in order to hit the deadline. On Disney’s

Beauty and the Beast, Glen Keane was the animator in charge of the Beast character, but he supervised seven other animators, in addition to assistant animators, breakdown artists and inbetweeners who all had to draw the character consistently as well as merging their work into a coherent performance. There’s a scene of the Beast learning to eat with a spoon that was animated by Tom Sito and based on actions he observed when his cat tried to eat from a spoon. Sito pitched the idea to Keane who accepted it, but the scene would have been done differently had another animator handled it.

This thesis will also examine live action reference, whether rotoscoped (which is tracing live action to turn it into drawings for cel animation) or motion captured (which uses hardware and software to capture a live performance and convert it into a computer animated character). Both these approaches are another layer of collaboration.

Not a lot has been written specifically on this topic; because people who write about animation are rarely animation professionals, they don’t understand the process or the repercussions of it. I’ve collected studio documentation from Disney, Warner Bros, Lantz and MGM that lists who animated specific scenes in a film. This has given me insight into the styles of individual animators as well as directors, who have very different approaches to assigning animators to characters or scenes. In addition, there is a large body of interviews with animation professionals that reveal the behind-the-scenes working methods.

With the exception of writings by Michael Barrier, who argues that casting by character results in better performances than casting by sequence, and Ed Hooks, who never deals with the issue of fragmentation, there really isn’t any critical writing on the nature of animated acting. In part, this thesis is an argument against Barrier’s position, as I don’t think he understands the degree of fragmentation that exists. Even when casting by character, I don’t know if animators ever have the same level of control that a live actor takes for granted.

I am familiar with an animator’s thought processes from personal experience. I am not familiar with an actor’s thought processes. I’m curious to know how similar they are and if differences are due to how theirjobs are organized or due to their nature of their crafts. I need to read more about acting, though I’m not sure that the material will turn out to be relevant to this thesis.

In writing this thesis, I have to be sensitive to how I use jargon and how much explanation is needed. If I was writing about what a film editor does or what a steadicam is, I know the readers would understand what I was talking about. However, I don’t think that the readers are going to understand what a inbetweener does or what an exposure sheet is, so I’ve got to make sure that I explain things so that readers can follow my argument.