Thursday, August 31, 2006

Bar Sheets and Metronomes

Because the marriage of picture and sound was one of the main selling points of cartoons in the early '30's, directors had to deal with musical beats in order to make the films work. Anyone who wants to try and puzzle out the approach finally has enough examples available to work with.

Actions and cuts were all placed on the beat in order to make the cartoon flow. Even if the music was not chosen before the animation, the director would still determine the beat so that when music was composed it would fit.

I know at Warner Bros. they had exposure sheets printed up that were marked for 8, 10 and 12 frame beats.

Which brings me to my metronome. People generally know that animators use stopwatches to figure out timing, but I never found them particularly useful. I needed something with smaller increments. I defy anybody with a stop watch to figure out the difference between 12 and 14 frames.

With a metronome, it's easy. And while you're listening to the metronome click away, you can be moving your finger or pencil over the page to simulate the action and get a feel for how long something takes.

At 24 frames per second, here's the relationship between frames per beat and beats per minute:

24 beat = 60 beats per minute

22 beat = 65 bpm

20 beat = 72 bpm

18 beat = 80 bpm

16 beat = 90 bpm

14 beat = 103 bpm

12 beat = 120 bpm

10 beat = 144 bpm

8 beat = 180 bpm

6 beat = 240 bpm

The formula is 60 divided by (frames-per-beat divided by 24) equals beats per minute.

When I was directing, I left the sheets blank during dialogue, since the length was predetermined and I wanted to give the animators some freedom. But whenever we got into action, I timed out everything. If a character was walking or running, I established the beat based on the metronome. I would determine how long an anticipation would last and how long an action would take. It was the only way to set a pace for a series of shots. As I could not guarantee that I would give a whole sequence to one animator, I had to establish the timing so if several animators did a sequence the pace would be consistent overall.

I don't think that I could animate or direct without a metronome. It was great if I could establish a musical beat that a composer would follow, but even if music was going to be slapped on, I was controlling the pacing of the action before any animation got done. It saved me time and gave me a predictable result.

Directors and animators who worked on cartoons timed on bar sheets came to know how things would look before they saw anything on screen. With computers, there's a tendency to do a bunch of board panels or poses and start sliding them around on a timeline to determine pacing. I don't know if people who do that develop a sense of timing, as they have to see the result before they know if it works.

Tuesday, August 29, 2006

More Freleng

The letter I printed from Freleng predated my attempt to work at his studio. I responded to it with a question about his crew and got a quick follow-up from him:

"The story men working for me at MGM were Joe Barbera, Allen Freleng (my brother), Hector Allen and Dan Gordon. The animators were Bill Littlejohn, Jack Zander, Emery Hawkins, Irv Spence, Richard Bickenbach and George Gordon."

Monday, August 28, 2006

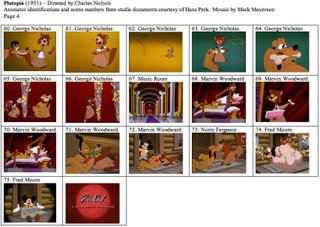

Jack Kirby's Birthday

August 28 is Jack Kirby's birthday. He would have been 89. His major contribution was to the comic book field, but he worked in animation in the 1930's, inbetweening for the Fleischer studio, and returned to animation in the 1970's and '80's, doing storyboards and design work for TV series. He's continued to be an influence in animation, particularly in the Bruce Timm versions of the DC comic book heroes.

August 28 is Jack Kirby's birthday. He would have been 89. His major contribution was to the comic book field, but he worked in animation in the 1930's, inbetweening for the Fleischer studio, and returned to animation in the 1970's and '80's, doing storyboards and design work for TV series. He's continued to be an influence in animation, particularly in the Bruce Timm versions of the DC comic book heroes. The above drawing is one of two Kirby pieces I own and the only one that's in pencil. I love it because it's pure Kirby, not Kirby worked over by an inker.

Those of us of a certain age were highly influenced by Kirby. There's a vividness to his characters and the way he told stories that hooked us and made us want to do it too. Before I ever thought of becoming an animator, I wanted to be a comic book artist like him. He's the reason that I learned how to draw.

For me, Kirby is like Chuck Jones, Bob Clampett or John Ford in that his personality and his work are inseparable. I value creators whose works are so personal that they couldn't be done by anyone else. Even their lesser works are interesting, as a chance to reflect on their strengths and weaknesses. And regardless of the quality, you always have the pleasure of their company.

Happy Birthday, Jack.

Sunday, August 27, 2006

I'm Late on Friz

August 21 was Friz Freleng's birthday and many blogs celebrated with material relating to Friz. Unfortunately, I was too busy to participate. However, I do have some letters from Friz regarding his time at MGM for the article I once wrote on that studio's cartoon history. Here's one of them:

February 24, 1976

Dear Mark:

My apologies for the long delay in answering your letter of the 3rd. I have been so involved in development for the new season, I have been unable to give your letter its deserving time.

I will have to admit that your information of me is more accurate than my own. I did not recall the picture titles of the M-G-M series until you mentioned them. (I am sorry that my memory does not serve me better.) Ther were a few other cartoons that I directed at M-G-M that I can recall, such as "The Mad Maestro" and "The Bookworm." (These were in color and under the Hugh Harman banner.)

I went to M-G-M after I was tempted by Fred Quimby through flattery of my work at Warners', and an increase to almost double of what I was earning at Warner Bros. Of course, afer I had committed myself to M-G-M, Leon Schlesinger offered me more to stay at Warners', but he was too late with his offer. I was committed to M-G-M in August, but my contract with Schlesinger expired in October 1939. [Mayerson here. I believe that Freleng got the year wrong and it should be 1937.]

During the period from August to October, M-G-M's top brass bought the rights to "Captain And The Kids." I balked at making these characters into an animated series and expressed myself thusly, but to no avail. M-G-M said they were dedicated to making good cartoons, and they thought that this being printed in so many papers would make it a popular cartoon. I was forced to prove them wrong.

Even though the M-G-M budgets were twice as much as Schlesingers, the creative freedom was lacking, and I knew I had made a mistake in leaving Warners'. When my contract expired, Schlesinger sent his manager over to see me and asked me to return. (Secretly I was more than happy to.) Quimby then went after Leon's second director, Tex Avery, who stayed with M-G-M until the studio closed. [Mayerson here. Avery definitely was gone to the Lantz studio before M-G-M shut down.]

I never regret the experience at M-G-M, but the politics under Quimby was unbelievable. I did not have the ability to cope with it.

After my return to the Schlesinger stable, I earned five Oscars for the studio. I supposed the experience away from Schlesinger gave me a new perspective, looking back now.

I stayed with Warners' until it closed, then David DePatie and I formed a partnership and took over the cartoon studio in 1963. We produced cartoons for United Artists, and when Warners' wanted more cartoons, we produced "Road Runner" cartoons and "Pink Panthers" at the same time.

When Warners' decided they wanted us exclusively, we balked at the idea, and they gave us a choice - Warner cartoons or the Pink Panthers. We chose Pink Panther. The result was, we were forced off of the Warner lot and had to build our own studio. Warners' then threw in the sponge and gaveup the cartoons permanently.

Enclosed is a photo that I hope will fill your requirements.

Best to you.

Sincerely,

Friz Freleng.

Le Deluge

I've finished my review of Amid Amidi's Cartoon Modern for fps. I'm not sure if it will appear in the next issue or in the fps blog, but the short review is that the book is excellent both as an art and history book. If you have any interest in '50's design or animation history, the book is worth owning.

Jim Hill has an interesting article about the flood of cgi animated features this year and how they're doing at the box office. It's generally not a pretty picture. There's going to be an avalanche of titles on DVD for Christmas, and what we currently see happening at the box office may be duplicated at the cash register. People's wallets hold finite amounts of cash and many of these DVDs will be passed over.

What's happened is an example of what's called emergent behavior. Lots of individuals make decisions for themselves that add up to a larger trend. In this case, producers saw how much money Pixar and DreamWorks were making and decided to go after some of it themselves. It's a kind of gold rush mentality. Somebody strikes gold and everybody converges on the area looking for their share.

The problem is that entertainment isn't like gold. There's a definite, measurable amount of gold in a given location, difficult as it may be to determine, but there isn't a definite, measurable amount of box office for any kind of movie. If the public gets tired, it's as if the gold in the ground turns to lead. Individual producers make decisions that add up to trends and so do consumers. Producers guess what the audience wants but the audience doesn't always cooperate.

When you're dealing with films that take years to create, it's easy to be late to the party. Sure, a good movie should always draw an audience, but the reality is that audience members have choices and don't always go where they're expected.

And it's also true that the time it takes to make these films may be enough for the audience to forget their boredom and be ready for more. I'm sure that Fox and Blue Sky are hoping exactly that when they announced yet another film starring cgi insects called The Leaf Men and the Brave Good Bugs. That's a title that I'm betting gets changed and we'll see if the bug reference makes it to the final title.

Tuesday, August 22, 2006

Posting Slowdown

Sunday, August 20, 2006

DVD Revenue for Live Action and Animation Writers

Steve Hulett, the business rep of The Animation Guild, is quoted in the article and has further comments on the TAG blog.

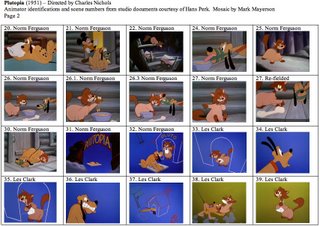

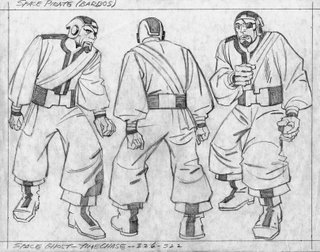

Plutopia Part 3

This led to a real difference in the quality of the Disney shorts. This cartoon is better animated than Mickey's Delayed Date due to the skills of the crew. Director Nichols takes advantage of this. He clearly casts Plutopia by sequence, with the exception of giving Moore the lion's share of Mickey scenes.

It's interesting to see how Moore's style changed from a cartoon like The Nifty Nineties. Mickey's snout is larger than in the earlier cartoon and his head is smaller in relation to his body. Moore's poses are still highly personal, but I don't think that his timing is quite as sharp as in earlier cartoons. There's sometimes a tendency for his characters to float between poses and they occasionally do here.

Scene 21 is credited to Ferguson, but it looks to me like Moore did Mickey in that shot and Ferguson only handled the dog.

One excellent piece of Ferguson's animation is Pluto lying down on the mat in scene 30, where he goes down in stages, each part of his body timed separately. It's a very funny piece of motion.

I wonder what Ferguson's drawings looked like in the '50's? There are published examples of his Pluto from the 1930's, but I don't think I've seen later examples. The thing that strikes me about Ferguson's version of Pluto in this cartoon is that it doesn't have a strong sense of design. I think that George Nicholas's version of Pluto is far more attractive looking. Ferguson's drawing also handicaps scene 31, where Pluto floats away in his dream. It's a tough scene due to the changes in size and perspective, but Ferguson (or his assistant) wasn't up to it. There is also some bumpy timing in that shot.

Ferguson was a supervising animator on Cinderella, Alice in Wonderland and Peter Pan. Does anybody know what he did on those films? I'm curious if Ferguson's drawing is noticeable on those features.

I've yet to see anything Les Clark animated that doesn't impress me. Clark gets the initial part of the dream sequence, where the characters' relationships are nailed down. Pluto is initially in revenge mode, taking sadistic pleasure from tripping the cat. The cat is remorseful and begs to be punished. This is all personality animation and Clark does a great job of putting the emotions across and establishing the dream's version of the cat.

George Nicholas draws a beautiful Pluto and has a real talent for strong, cartoony poses. Take a look at these:

His shapes are very flexible and he uses a lot of drag on the fleshy parts of the cat, which results in a beautiful looseness. Until the 1950's, Nicholas was mainly a shorts animator but he did get his chance to animate on features like Cinderella and Lady and the Tramp. I hope that we can identify more Nicholas work on the shorts, as I think that he's deserving of more attention.

Marvin Woodward brings up the rear, taking care of the transition from the end of the dream back to reality. By the time Woodward's scenes appear, all the heavy lifting has been done and Woodward's scenes have no surprises to deliver. Ferguson gets the final fight scenes and Moore finishes up the cartoon with Mickey.

Note the changes in background colors, keyed to the cat's emotional shifts. This is the kind of thing that Clampett did in the later Warner cartoons and it's interesting to see Disney picking up on it. The dream background sets and props are also very much in a UPA vein. Disney had no problem going with a graphic approach in a dream sequence here as they had done in the Pink Elephants dream in Dumbo.

Once again, I'm at a loss to know why this cartoon doesn't get more attention. Besides the outrageous content, there's excellent animation here and some bold, attractive graphic backgrounds. I think that this cartoon is an under-rated gem and if you haven't seen it, I hope that you'll seek it out.

Thursday, August 17, 2006

History and Business Links

Michael Sporn has been publishing pictures from a 1940 book called Film Guide Handbook: Cartoon Production. The stills are all taken at Disney, and many of them haven't been published elsewhere. Here's part 1, part 2, part 3 and part 4. Make sure to read the comments, as many of the people in the photos are identified there.

The Animation Guild blog is putting up drawings by animation artists from the 1940's including work by Virgil Partch (satirizing Ollie Johnston and another entry satirizing the aging of the inbetween crew), George Gordon (satirizing a 1940 MGM cartoon dept. golf tournament), and a 1929 caricature by Jack King of the Disney staff.

Over at the ASIFA-Hollywood blog, they've put up a lot of model sheets from UPA that I've never seen before. There's work from the Gerald McBoing Boing and Magoo films, but there's also artwork from lesser known UPA cartoons like Georgie and the Dragon, directed by Bobe Cannon, and The Popcorn Story, directed by Art Babbitt.

Amid Amidi has posted photos of artists of the 1950's who are the subject of his new book Cartoon Modern. I'll be reviewing this book for fps and just got my copy today. I haven't read a word of it yet, but the art is fantastic. If you're interested in 1950's design, one flip through this book and you'll know that you have to own it. And I'm confident, based on Amid's Animation Blast magazine, that the text will be highly informative.

UPDATE: The comic book history magazine Alter Ego is a place you wouldn't ordinarily look for for animation history. However, the current issue (#61) has a history of the American Comics Group, which published funny animal comics that were drawn by many animation personnel. The history includes interview material with Jim Davis (not the Garfield Jim Davis; the animator who worked for everyone from Harman-Ising to Filmation) and there's information on and artwork by the likes of Ken Hultgren, Jack Bradbury, Dan Gordon, Bob Wickersham, Hubie Karp and Cal Howard.

On the business side, here's an article about how documentary film makers are dealing with problems caused by copyright and how Kirby Dick, whose movie This Film is Not Yet Rated will be released without copyright clearances and defend itself based on the "fair use" section of the U.S. copyright law. I'm waiting for some kind of tipping point where copyright is either going to completely break down or undergo a radical change. I think that pressure for this is building on multiple fronts.

I don't play video games. However, there's no question that they represent a very large part of the current animation industry. Peter Moore was the former head of Sega U.S. and is now in charge of the Microsoft Xbox. He talks about 7 ways that the game industry can make itself more open to both audiences and talent. Most of what he says can be applied to animation studios doing entertainment as well.

Tuesday, August 15, 2006

Plutopia Part 2

Once the Hays Code kicked in around 1934, all Hollywood movies including cartoons got tamer. Sex was particularly taboo. While there were performers with gay personas like Franklin Pangborn, their gayness was portrayed as fussiness and affectation. It was out of the question that they could interact with other men on a romantic or sexual basis.

Under the Hays Code, animated lust turned into exhuberance. Avery's wolf is the best example of this. The gags were built on visual variations of arousal, but consummation was out of the question. It's doubtful that Avery could have gotten away with even this except that there was a war on and the Hays office loosened up for the sake of national morale.

After the war, things got even tamer than before. Racial caricatures pretty much disappeared except for Speedy Gonzales. Bugs Bunny cross dressed, but that was done to showcase his antagonist's stupidity or neediness. Avery moved from sex to other topics.

The Disney studio's position was probably tamer than most. While there were some sexy girls in Disney films in the 1940's (Sluefoot Sue in Pecos Bill; the girl in Duck Pimples; Donald chasing live girls in The Three Caballeros), by the '50's it was back to classic stories and talking animals.

So where did Plutopia come from? And how did it escape without anybody seeming to notice? If you're not familiar with this cartoon (and I hate to spoil it for you), in Pluto's dream the cat is portrayed as a gay masochist who gets off when Pluto bites his tail. Pluto is happy to oblige as he's rewarded with bones (the phallic imagery is inescapable). Pluto and the cat are both receiving the oral gratification they crave.

Was the Hays office asleep at the switch? They never would have let a live actor portray masochism in anything other than a film set in an asylum. Did Walt Disney understand what this cartoon was really about? And where did the idea come from? It's completely atypical in Charles Nichols' directing career. It doesn't appear that there was anybody new on the crew who might be responsible.

Was it the result of somebody's repressed life surfacing or did somebody decide to see how much they could get away with? How much did Jim Backus, the voice of the cat, add to the characterization? And was the crew laughing hysterically while they made this cartoon or did they just not get it?

What about animation fans? While they search out pre-code cartoons from Fleischer, Iwerks, Harman-Ising and Van Beuren for their outrageousness, pine for the WB censored 11, and dream of John K. cartoons created without censorship, do they realize what's in Plutopia and that it's available in a pristine copy?

Maybe it's because nobody pays attention to Pluto. That's the only answer I can offer for how this cartoon got out in the first place and for how little attention it gets. But I sure wish I knew who dreamed this one up and how they got it into production.

Monday, August 14, 2006

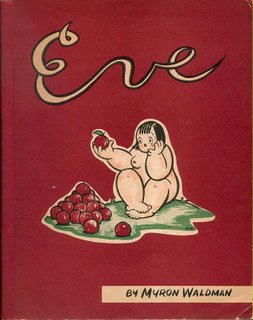

Myron Waldman's Eve

I was aware of this book but had never seen a copy before Josh Kaell showed me his. It's a 1943 paperback graphic novel, told without words, by Fleischer head animator Myron Waldman. You can see the Fleischer influence in the Boop-ish design of Eve's face. The book was published by Stephen Daye, a New York publisher I've never heard of.

I was aware of this book but had never seen a copy before Josh Kaell showed me his. It's a 1943 paperback graphic novel, told without words, by Fleischer head animator Myron Waldman. You can see the Fleischer influence in the Boop-ish design of Eve's face. The book was published by Stephen Daye, a New York publisher I've never heard of. The story is about a N.Y. secretary who pines for romance and finds it in Miami, another Fleischer connection as the studio had spent several years there before Paramount brought it back to New York.

The interior drawings are completely black and white, drawn with a brush.

Waldman was the most sentimental and gentle of the Fleischer head animators. That was apparent in his creation of Betty Boop's dog Pudgy and his direction of the Fleischer two-reel version of Raggedy Ann and Andy. This story is reflects the same sensibility in print form.

There are three copies listed at AbeBooks.com. They're not cheap, but Josh found his copy for less than those listed, so keep your eyes open at used book stores and flea markets.

Plutopia Part 1

Sunday, August 13, 2006

Mickey's Delayed Date Part 3

After the war, Jack Hannah was promoted to directing Donald Duck. He re-invigorated those cartoons with sharper timing, stronger conflict and introduced new characters into Donald's world. Jack Kinney was still directing Goofy and while Goofy was increasingly put in suburban situations, at least they were satirical. As a director, Charles Nichols was not particularly daring in terms of staging, timing, gags or graphics. Mickey, in Nichols hands, became a fall-guy, someone who had to struggle to deal with life's little setbacks. Ho-hum.

Apparently there wasn't a lot of enthusiasm for Mickey during this period, as there were no Mickey cartoons made at all in 1949 and '50 and never more than two in any other post-war year. By contrast, there were 5 Donalds and 5 Goofys in 1953, the year of Mickey's last cartoon.

The animation is this cartoon is not remarkable, and it's telling that the best animation is probably on Pluto and not Mickey.

Bob Youngquist draws the Mickey and Minnie well but he's not given anything particularly interesting to do with the characters. Minnie comes off as a little shrewish, probably due to the social mores of the time rather than anything having to do with Youngquist.

Harry Holt handles just a couple of Mickey acting scenes in the beginning. His work is very pose oriented and Mickey's face is a bit mushy. Holt is much stronger on the action scenes he animates when Mickey's running on the street.

George Kreisl might do the best animation in this cartoon with his work on Pluto. He's excellent at making Pluto's face expressive. He's not afraid to go off model as his design sense makes for pleasing drawings. Kreisl gets the last shot of the cartoon, and an animator didn't get the fade-out unless he had the full confidence of the director.

George Nicholas is almost as good. He gets the typical sequence where Pluto gets frustrated interacting with something, which dates back to Norm Ferguson's animation of Pluto and the flypaper in 1934. He also gets some strong action scenes of Mickey chasing his top hat. He also brings a strong sense of design to both characters and isn't afraid to distort them as a result.

Jerry Hathcock seems versatile, handling both Mickey and Pluto well. Hathcock gets some good acting and action out of Pluto. By coincidence, Jenny Lerew recently posted a drawing Fred Moore did of Hathcock's son, Bob.

Marvin Woodward brings up the rear, handling the Mickey-Minnie relationship scenes the same way he did in Mickey's Birthday Party. He's given the strongest Mickey acting scenes in the cartoon and does them justice before Kreisl gets the fade-out.

At the time this cartoon was made, only Woodward had extensive feature experience, though Youngquist worked on Fantasia. The rest were strictly shorts animators, though Kreisl, Hathcock, and Nicholas would get their licks in on features during the '50's. Later Mickey cartoons benefited from stronger animators like Moore and Ferguson, though that was an indication of their falling status at the studio.

Thursday, August 10, 2006

Mickey's Delayed Date Part 2

Mickey's voice was probably provided by James MacDonald, who took over the voice halfway into "Mickey and the Beanstalk" in Fun and Fancy Free. I don't know who was providing Minnie's voice at this point. Beyond voice people, there are no credits for assistants, inbetweeners, inkers, painters or camera operators. Even with the studio documentation, we can't tell which effects animation was done by Engman or by Jack Boyd. They're listed as effects directors, but did they have a staff or did they just split up the work themselves? Did Boyd get the credit based on footage, which is how animator credits were determined, or did they just alternate?

This cartoon was released in 1947 and by then, Disney was no longer willing to lavish large budgets on the shorts. Charles Nichols later directed at Hanna-Barbera for years doing TV cartoons and the seeds of a TV directing style can be seen here. Most shots feature just a single character, which saves animation. More often then not, a cut is not on a single character's action (which would require planning a hook-up drawing), but from one character to another. Even if a character is in two consecutive shots, the character is often off-screen at the end of the first shot or the start of the second. All this makes it easier to assign shots to animators without them worrying about what's happening in the surrounding shots. It also means that shots can be animated in any order without creating continuity problems.

Another economical aspect of the directing is the heavy re-use of layouts and backgrounds. The first six shots of Minnie use identical set-ups. Scene 2 gets an overlay, but the rest are completely the same. Many of the other backgrounds are used at least twice.

This is quite a change from a cartoon like Mr. Duck Steps Out, made just 7 years earlier. It is full of multi-character shots and often cuts on action. Nichols' approach is far more stripped down than Jack King's. It ain't as pretty, but it's more cost-effective. In the post-war period, with falling movie attendance and rising costs, the short cartoons from all the studios felt the financial pinch and even Disney was not immune.

Financial Advice

Wednesday, August 09, 2006

Traffic Jam

Tuesday, August 08, 2006

The Perils of Public Animation Companies

I wrote an article for fps (you’ll have to pay to read it) stating that with the exception of the games industry, there really wasn’t an animation industry. Animation was a division of larger media industries. The exceptions at the time of the article were Pixar and DreamWorks. Of course, Pixar recently sold itself to Disney, leaving only DreamWorks as an independent animation-only company.

I don’t envy their position. Animation companies do not have good track records for surviving with animation as their only product. Disney was forced to go public to raise money in April, 1940. Prior to that, the company had been family-owned. It was a necessary move, but the 1940’s were probably Disney’s worst decade financially. World War II cut off the foreign market, responsible for a good portion of his revenue. In addition, the U.S. public was not as enthusiastic for the features following Snow White, even though they generally cost more to produce. The ‘40’s were further complicated by the employee strike and the work for the U.S. government. The government films saved the studio financially but still absorbed an enormous amount of the studio’s resources.

What saved Disney was the studio diversifying beyond animation. In the late ‘40’s, the studio began to make live action films. In the early ‘50’s, Disney got involved in TV and of course, Disneyland opened. When Sleeping Beauty failed at the box office in 1959, it was a financial setback, but it did not threaten the continued existence of the company.

Pixar was an incredibly lucky company. Certainly their skills contributed to their success, but their films were consistently profitable at the box office in ways that other film companies could only envy. However, with the exception of Renderman software, their features were their only product. With only one film per year, a failure would have devastated the company’s stock price and probably forced major layoffs. Stephen Jobs’ solution was to sell the company to Disney, hitching his wagon to a more diversified company. A Pixar failure will no longer threaten the division’s existence.

Which leaves us with DreamWorks. When it was formed, it attempted to be a complete media company. There was a music division, a TV division, a live action feature division and, of course, an animation studio. Just as Walt Disney was the victim of events beyond his control in the 1940’s, DreamWorks has similarly suffered. Their TV division was hurt badly by Disney’s acquisition of ABC and the networks’ tendency to buy shows from their own production companies. DreamWorks’ music division was formed at a time of shrinking CD revenues and online file trading. While their live action division had success in the marketplace, there wasn't enough success to justify its continued existence as an independent company and it has been sold to Paramount.

The animation studio was the most profitable part of DreamWorks, so it was spun off as a public company. With two studios going full tilt and an output deal with Aardman, DreamWorks is capable of releasing two features a year. However, that means that each film’s revenue (films, DVD’s, TV sales, merchandising, etc.) represents half of the company’s potential annual income.

The company tried to diversify into TV with Father of the Pride, but the series failed to make it to a second season.

Due to the failure of the other divisions and its reliance solely on animation, DreamWorks is kind of like Disney going in reverse. Instead of diversifying, it’s become more of a monoculture. An animated failure will have a strong negative effect on the company’s bottom line.

Jeffrey Katzenberg is no fool. I think that his creation of DreamWorks after leaving Disney is, from a business standpoint, a far greater achievement than Walt Disney replacing Oswald the Rabbit with Mickey Mouse. I don’t know what the future holds and I can’t begin to guess what’s going on in Katzenberg’s head, but if history is any indication, there are basically two options. DreamWorks can attempt to diversify into other media to cut animation’s risk (the Disney model) or it can sell itself to a more diversified media company (the Pixar model). Katzenberg has defied the odds before and may do so again, but I’m betting that something will have to change within the next three to five years.

(For the record, this is the 100th post on this blog. Two were by John Celestri (Thanks, John!) but the rest have been by me. I've got to tell you, this is a lot harder than it looks.)

Monday, August 07, 2006

Catching Up

Didier Ghez, editor of the much respected series Walt's People, (a collection of interviews with people who worked at and with Disney) has started a blog devoted to Disney history. He mentions that Walt's People volume 4 is on track for December publication.

Over at John K's blog is an article by Milt Gray on animation timing and how it has changed from the days of Bob Clampett to the current crop of animated TV series. Having worked in TV myself and attempted to swim against the current, I'm amazed at how the role of director in TV animation has been diminished. The director often does no more than approve boards, timing and call for retakes, a far cry from what could be done to shape an episode. As Milt interviewed Clampett extensively and has worked for years himself as a director and timer on The Simpsons, his observations carry the weight of personal experience.

Keith Lango applies his personal experience to talk about The Ant Bully and why he believes it failed to click with audiences. As an animator on the project, Keith is surprisingly frank in his assessment. His thoughts on the two motivations for making films strikes me as spot on.

Mark Kennedy has an excellent post on design and drawing. There are artists whose work we viscerally respond to and those whose work leaves us cold. Often, we can admire an artist's craft or knowledge and still not love the work. I think that Mark has determined one important reason why this is the case and if you agree with him, you'll look at your own drawings in a new light.

Business Week has an article on YouTube and the copyright problems that it faces. I stand by my belief that a major copyright overhaul is needed to allow web video to flourish and to guarantee creators compensation. Otherwise, the only people who'll make money from web video are lawyers.

Sunday, August 06, 2006

Definitions

In live action, movement exists in real time in the real world. It’s observable without any technology. On film or on tape, live action is the re-creation of motion through the rapid display of still images. The key word there is “re-creation.” The motion already exists. It’s recorded by sampling it at a given frame rate (24, 30 or some other number of frames per second) and then when those sample images are displayed in rapid succession, our flawed eyes see them as moving.

The flaw in our eyes is referred to as persistence of vision. When an image is removed from in front of us, it remains on our retinas. Movies and TV use this flaw to replace the old image with a new one before the old one fades away. Our retinas are just not fast enough to keep up with what’s actually happening.

In the case of animation, no motion exists in the real world for recording purposes. Animation is the creation of the illusion of motion through the rapid display of still images. That’s as basic as it gets, yet it’s open enough to encompass a lot.

Chuck Jones pointed out that you don’t need a camera for animation. All you need is a stack of paper and something to mark it with. Norman McLaren did away with cameras and paper when he drew on film. Both these approaches provide a way to rapidly display still images (either by flipping or projecting them) without any recording device at all.

Beyond the basic definition, animation borrows a lot. Like live action film, it borrows narrative and character. It also borrows the use of sound, whether dialogue, sound effects or music. It borrows the use of colour. Finally, it borrows design.

None of these things is necessary to make an animated film and there are examples that lack each of the above. There are abstract films that avoid narrative and characters. The silent period did without sound and color of any kind.

Design enters the picture when somebody has to create the object or image that will be used to create the illusion of motion. All drawn and cgi animation has to be designed. Stop motion can be, but doesn’t have to be. J. S. Blackton’s The Haunted Hotel manipulates real objects a frame at a time. A more modern equivalent would be Roof Sex (parental discretion advised; sexual situations involving naked furniture). In both these films, the design isn’t created so much as borrowed. Willis O’Brien, Ray Harryhausen and Art Clokey are examples of stop motion animators who do design the objects that they manipulate.

Because so much of animation has revolved around the creation of images and objects, there’s confusion about the relationship of design to animation. Good design is a plus, but as stop motion shows, design itself is not a necessary part of our medium.

When critics talk about Monster House or A Scanner Darkly, they are confusing design (the look of cgi or drawn animation) with animation itself. As the motion in these films originates in real time in the real world, it’s not animated. The films are re-creations of movement, not creations of it.

Saying that something is not animation is not a criticism; it’s simply a statement of fact.

These days, we are getting into gray areas. If a character’s body movement has been motion captured but the face has been animated, how do you describe that character? Do we need to determine percentages before we can call a character or film animated or not? I don’t know the answer to this.

My impression of Monster House and A Scanner Darkly is that they’re both live action films that have used animation design the way the might have used costumes and make-up in the past. Nobody would claim that Bert Lahr’s cowardly lion in The Wizard of Oz was animated. If Lahr was alive today and wired up to drive a cgi character or if his image was overlaid with artwork created with digital paint software, people might be confused and call it animation, but they would be wrong. If the motion exists in the real world and the resulting images are re-creations of that motion (even if they’ve been doctored) they’re not animation.

Media Moves

Disney, meanwhile, sharply changed course under Mr. Iger, its new chief executive, who acquired Pixar Animation for $7.4 billion earlier this year. He then went further and scaled back Disney’s own feature film production.

As the analyst Richard Greenfield of Pali Capital noted in a report last week, Pixar’s “Cars” has earned less overseas than the last Pixar hit, “The Incredibles,” trailing it by an average of 54 percent in five countries, including Britain and Japan, after several weeks of box-office results.

While it may be too early to judge the ultimate success of the Pixar acquisition, “it is certainly worth considering how much lower Pixar’s stock would be today” because of “Cars,” Mr. Greenfield wrote. It was a polite way of asking: Just how much did Disney overpay?

For now, at least, it may not matter. The market applauded Mr. Iger’s aplomb in grabbing Pixar and bringing its leaders, John A. Lasseter and Steven P. Jobs, into the Disney fold. Since the Pixar deal was announced, Disney shares have climbed 15 percent, adding $8.7 billion to the company’s market capitalization.