Disney historian Jim Korkis's latest book is Who's Afraid of the Song of the South? and Other Forbidden Disney Stories. The main section of the book is an in-depth look at the production of the film that Disney has chosen to suppress.

While Korkis deals with the current controversy surrounding the film, he traces the film's origins and shows that the controversy started even before the film was released. In the period after World War II, when the U.S. had defeated a fascist power that claimed it was racially superior, Black Americans felt strongly that it was time for the United States to abolish its own discriminatory practices. That included the portrayal of Black people in popular culture. Black audiences were no longer satisfied with stereotypical screen portrayals of porters, maids and lazy or frightened comedy relief.

In the post-war years, Hollywood began to tackle discrimination in live action films such as Gentleman's Agreement (1947), which dealt with discrimination against Jews, and Pinky (1949), where a Black woman passes for White before returning to her own community. But it wouldn't be until the 1950s and the rise of Sidney Poitier before Black performers were cast in leading roles that were dramatically respectable.

Song of the South (1945) sits at the cusp between pre- and post-war racial attitudes and as Korkis shows, that's one of the things that makes the film hard to deal with. The various screenwriters included a southerner with typical racial views as well as a left-leaning victim of the blacklist. Black actor Clarence Muse was hired as a consultant, but left the project over the film's racial attitudes, yet Muse himself later appeared in films like Riding High (1950) and The Sun Shines Bright (1953), neither of which could be considered racially progressive. The reviews of the time also straddle changing racial attitudes, with some wholly praising the film while others expressing reservations on its treatment of race.

Korkis covers the writers, the cast, the production of the live action, the animation, the music, the reviews and the controversy surrounding the film. Beyond the race issue, the film is important for other reasons. It was Disney's first foray into a feature dominated by live action. It was photographed by Gregg Toland, cinematographer of The Grapes of Wrath (1940) and Citizen Kane (1941), and this was Toland's first film in colour. Bobby Driscoll and Luana Patten, the child stars in the film, went on to other star in other Disney films, making them the first live performers under contract to the studio. It was also the first Disney live action film to receive an Oscar, albeit an honorary one for James Baskette, who played Uncle Remus.

Korkis also writes about how the animated characters were used in other Disney projects such as Splash Mountain and various comics and other publications.

The balance of the book is a bit of a hodge podge, lacking the strong focus of the first 100 pages. Some of the material is related, such as the deleted Black centaurette in re-releases of Fantasia. While the material covered is interesting, such as Disney's failed attempts to craft films based on the Oz books and John Carter of Mars before the films that were eventually released, this material could hardly be described as "forbidden." Korkis is a thorough historian and the material is interesting, but as a book, it doesn't hang together as strongly as it might.

Be that as it may, there's a wealth of interesting Disneyana here. Korkis's dedication to shining light into the nooks and crannies of Disney history always produces surprises for the reader and fills out the picture of Walt Disney and the company he created. As the current Disney management would prefer to forget the existence of Song of the South, this book serves as the closest the film is likely to get to a "making of" book.

Sunday, December 30, 2012

Monday, December 17, 2012

Kimball Christmas Cards

If you aren't visiting Amid Amidi's site 365 Days of Ward Kimball, you're missing out on some beautiful art. Currently, there's lots of Christmas related artwork.

During his talk on Kimball at the Ottawa International Animation Festival last September, Amidi made it a point to say that Kimball's style was evolving towards more modern graphics in the 1940s. The above cards (1945 on top and 1946 on the bottom) are great examples of the turn Kimball's style was taking. Both are, of course, well drawn. But while the 1945 card is conventional in its use of perspective and structure, the '46 card breaks away from realistic perspective and revels in flattening out shapes. While UPA would animate this stylistic approach a couple of years later, Kimball was prepared to do so but wouldn't get the chance until Melody, Toot Whistle Plunk and Boom and the TV episodes he directed for the Disneyland series in the 1950s.

Darrell Van Citters Interviewed

This week marks the 50th anniversary of Mr. Magoo's Christmas Carol, the first animated TV special. Darrell Van Citters has written the book on the making of the show and film historian Frank Thompson interviews Van Citters on his podcast The Commentary Track.

Thompson has also interviewed Cartoon Brew's Jerry Beck but those of you interested in film history in general will be interested in other Thompson podcasts, which include interviews with character actor L.Q. Jones (talking about working with John Ford, Sam Peckinpah, and Budd Boetticher), and film historians Rudy Behlmer, Kevin Brownlow, Robert S. Birchard, John Bengston, Randy Skredvedt and Joan Myers.

Friday, December 07, 2012

The Difference Between Walt Disney and Robert Iger

From Seth Godin:

"Capitalists take risks. They see an opportunity, an unmet need, and then they bring resources to bear to solve the problem and make a profit.

"Industrialists seek stability instead.

"Industrialists work to take working systems and polish them, insulate them from risk, maximize productivity and extract the maximum amount of profit. Much of society's wealth is due to the relentless march of productivity created by single-minded industrialists, particularly those that turned nascent industries (as Henry Ford did with cars) into efficient engines of profit.

"Industrialists don't mind government regulations if they write them, don't particularly like competition or creativity or change. They are maximizers of the existing status quo."

Friday, November 23, 2012

Who Owns History? Who Owns Culture? Who Owns Speech?

The Walt Disney company is responsible for delaying the publication of Full Steam Ahead!: The Life and Art of Ward Kimball by Amid Amidi. The reason, according to the author, is that Disney is unhappy that Kimball's life doesn't conform to the company's exacting standards. Disney has had the book since January of 2012 and has yet to approve it. The publication of the book has been delayed a minimum of seven months, preventing those who pre-ordered the book from reading it and delaying earnings for both the author and publisher.

I have not read the book and I certainly don't know the specific text that Disney is objecting to, but I find this situation to be very troubling for the chill it casts over our ability to comment on the world we live in.

We are now in a time where entertainment corporations have run amuck. I have recently written about Sony taking ownership of any artwork submitted by job applicants. In Finland, the police have confiscated the laptop of a nine year old girl for downloading a single song from the Pirate Bay. In addition, they have fined the girl 600 Euros, even though the girl's father has proved that the girl later bought the album and concert tickets for the band in question. Several countries have instituted laws where three copyright violations can result in a user being banned from the internet altogether.

One of the problems with this ban is how arbitrarily copyright violations are enforced. All over the web, there are sites which could be construed to be violating copyright. I say "could be" as a court could decide that material qualifies as fair use. And the copyright holder gets to selectively decide who to prosecute and who to ignore. In other words, if the company thinks the copyright violation is good marketing, it will turn a blind eye.

Beyond the logistics of corporations using the law to arbitrarily punish people, there is the much larger question of who owns history, culture and speech? When culture is manufactured for a profit, do we have the right to discuss it, criticize it and respond to it? Can we use examples to make our case or are we limited by the legal rights of the manufacturer?

As the entertainment corporations are now multinational behemoths with whole staffs of lawyers charged with protecting intellectual property, they use the threat of legal action as a deterrent. The Kimball book is a case in point. In court, it could be argued that any Disney artwork used in the book is fair use. What's one still image from the more than 100,000 frames in a feature film? How is the publication of a still depriving Disney of income? Disney could not suppress a book based on its text without proving libel, but it can suppress a book before the fact by denying the use of artwork and the threat of a lawsuit if a publisher decides to take a chance and publish anyway.

Unfortunately, this is not an isolated incident. Disney owns Marvel and denied Sean Howe, the author of Marvel Comics: The Untold Story, the use of illustrations unless they could approve the text of the book. Howe and his publisher decided to forgo illustrations, so the history of a comic book company has no images of the artwork that made the company worth writing about. And as I mentioned above, copyright prosecutions are arbitrary. Howe has a tumblr where he has included images that should have been included in the book and so far, Disney hasn't complained.

How strange is it that in the western world, it is permissible to comment on governments but not on companies that make cartoons? As corporations have increasingly lobbied governments to write laws for their own benefit, we may soon reach a point where criticizing governments is irrelevant and the corporations who should be criticized will stifle all dissent.

I have not read the book and I certainly don't know the specific text that Disney is objecting to, but I find this situation to be very troubling for the chill it casts over our ability to comment on the world we live in.

We are now in a time where entertainment corporations have run amuck. I have recently written about Sony taking ownership of any artwork submitted by job applicants. In Finland, the police have confiscated the laptop of a nine year old girl for downloading a single song from the Pirate Bay. In addition, they have fined the girl 600 Euros, even though the girl's father has proved that the girl later bought the album and concert tickets for the band in question. Several countries have instituted laws where three copyright violations can result in a user being banned from the internet altogether.

One of the problems with this ban is how arbitrarily copyright violations are enforced. All over the web, there are sites which could be construed to be violating copyright. I say "could be" as a court could decide that material qualifies as fair use. And the copyright holder gets to selectively decide who to prosecute and who to ignore. In other words, if the company thinks the copyright violation is good marketing, it will turn a blind eye.

Beyond the logistics of corporations using the law to arbitrarily punish people, there is the much larger question of who owns history, culture and speech? When culture is manufactured for a profit, do we have the right to discuss it, criticize it and respond to it? Can we use examples to make our case or are we limited by the legal rights of the manufacturer?

As the entertainment corporations are now multinational behemoths with whole staffs of lawyers charged with protecting intellectual property, they use the threat of legal action as a deterrent. The Kimball book is a case in point. In court, it could be argued that any Disney artwork used in the book is fair use. What's one still image from the more than 100,000 frames in a feature film? How is the publication of a still depriving Disney of income? Disney could not suppress a book based on its text without proving libel, but it can suppress a book before the fact by denying the use of artwork and the threat of a lawsuit if a publisher decides to take a chance and publish anyway.

Unfortunately, this is not an isolated incident. Disney owns Marvel and denied Sean Howe, the author of Marvel Comics: The Untold Story, the use of illustrations unless they could approve the text of the book. Howe and his publisher decided to forgo illustrations, so the history of a comic book company has no images of the artwork that made the company worth writing about. And as I mentioned above, copyright prosecutions are arbitrary. Howe has a tumblr where he has included images that should have been included in the book and so far, Disney hasn't complained.

How strange is it that in the western world, it is permissible to comment on governments but not on companies that make cartoons? As corporations have increasingly lobbied governments to write laws for their own benefit, we may soon reach a point where criticizing governments is irrelevant and the corporations who should be criticized will stifle all dissent.

Tuesday, November 20, 2012

More Artist Exploitation

In the past, if you pitched an idea to a studio, they would ask you to sign a release form before pitching. The form stated that the studio might already be developing a property similar to what you were about to pitch and that you acknowledged this. The purpose of the form was to prevent the people pitching from launching lawsuits if they felt their ideas had been stolen by the studios. In truth, at any given moment, studios have multiple properties in development and coincidences do occur. There were also cases where the release forms allowed studios to rip off ideas without paying for them.

However, the release form made no claims to ownership of the material being pitched. The pitcher was free to take the material anywhere else.

The world has changed for the worse. Sony is hiring storyboard artists and visual development artists. They are not looking for ideas here; they are looking for artists who can draw and develop ideas that Sony will provide. It is clearly a work-for-hire arrangement. Yet Sony, in its terms of use portion of the online application for both jobs states this:

7. Submissions

Subject to applicable law and except as otherwise expressly provided in any other agreement that you (or your employer if you are not employed by SPE) may have with SPE with respect to the resources made available on this Site (a “Base Agreement”):

• You agree that any intellectual property or materials, including but not limited to questions, comments, suggestions, ideas, discoveries, plans, notes, drawings, original or creative materials, or other information, provided by you in the form of e-mail or electronic submissions to SPE, or uploads or postings to this Site (“Submissions”), shall become the sole property of SPE to the fullest extent permitted by applicable law and will be considered "works made for hire" or "commissioned works" owned by SPE;

• To the extent that any Submission may not constitute a "work made for hire" or "commissioned work" owned by SPE under applicable law, you hereby irrevocably assign, and agree to assign, to SPE all current and future right, title and interest in any and all such Submissions; and

• SPE shall own exclusive rights, including any and all intellectual property rights, and shall be entitled to the unrestricted use of Submissions for any purpose, commercial or otherwise, without acknowledgment or additional compensation to you.

In the event applicable law operates to prevent such assignment described above, or otherwise prevents SPE from becoming the sole owner of any such Submissions, you agree to grant to SPE, and this provision shall be effective as granting to SPE, (with unfettered rights of assignment) a perpetual, worldwide, paid-in-full, nonexclusive right (including any moral rights) and license to make, use, sell, reproduce, modify, adapt, publish, translate, create derivative works from, distribute, communicate to the public, perform and display the Submissions (in whole or in part) worldwide and or to incorporate it in other works in any form, media, or technology now known or later developed, for the full term of any rights that may exist in any such Submissions.

By making Submissions, you represent that (i) you have full power and authority to make the assignment and license set forth above, (ii) the Submissions do not infringe the intellectual property rights of any third party, and (iii) SPE shall be free and have the right to use, assign, modify, edit, alter, adapt, distribute, dispose, promote, display, and transmit the Submissions, or reproduce them, in whole or in part, without compensation, notification, or additional consent from you or from any third party.

Essentially, the above states that Sony takes ownership of your portfolio material when you apply for the job. If you are submitting samples of work you have done for other companies, Sony wants you to assign the rights to them. You clearly don't have the authority to do that for work you don't own, so that means that you are not legally allowed to show Sony work you've done for other companies. Sort of defeats the purpose of a submission portfolio, doesn't it?

What's clearly disturbing though, is that any original work in your portfolio becomes their property. This does not depend on whether they hire you or not, they get ownership because you applied.

How absurd is this? It means that legally, you could not take your own work and use it to apply to another company later, as it would now be owned by Sony. Furthermore, what right does Sony have to take ownership of your work without payment? And of course, it's not enough that Sony owns it, they list all the ways that they can use and mutilate your work "without compensation, notification, additional consent from you or from any third party."

Sony's lawyers have been overzealous here. It means that nobody should be applying for these jobs, as you can't show them your work for others and shouldn't show them your personal work.

Undoubtedly, someone will say it's just boilerplate. Sony would never exercise these rights, they're just trying to protect themselves. People sign what they have to in order to get work. But it remains a legal document unless it is successfully challenged in court, and that takes time and money.

Imagine this scenario. I may hire you, but before you apply, I say you have to sign an I.O.U. for $100,000. I have no intention of ever collecting. It's just a formality. But the fact remains that by applying to work for me, you've given me the right to collect $100,000 from you. Would you want that hanging over your head? Would you want to hire a lawyer and go to court if I decide to collect? Isn't it doubly absurd if I don't hire you and never pay you a nickel but still want the $100,000?

Sony needs to rewrite their terms of use.

However, the release form made no claims to ownership of the material being pitched. The pitcher was free to take the material anywhere else.

The world has changed for the worse. Sony is hiring storyboard artists and visual development artists. They are not looking for ideas here; they are looking for artists who can draw and develop ideas that Sony will provide. It is clearly a work-for-hire arrangement. Yet Sony, in its terms of use portion of the online application for both jobs states this:

7. Submissions

Subject to applicable law and except as otherwise expressly provided in any other agreement that you (or your employer if you are not employed by SPE) may have with SPE with respect to the resources made available on this Site (a “Base Agreement”):

• You agree that any intellectual property or materials, including but not limited to questions, comments, suggestions, ideas, discoveries, plans, notes, drawings, original or creative materials, or other information, provided by you in the form of e-mail or electronic submissions to SPE, or uploads or postings to this Site (“Submissions”), shall become the sole property of SPE to the fullest extent permitted by applicable law and will be considered "works made for hire" or "commissioned works" owned by SPE;

• To the extent that any Submission may not constitute a "work made for hire" or "commissioned work" owned by SPE under applicable law, you hereby irrevocably assign, and agree to assign, to SPE all current and future right, title and interest in any and all such Submissions; and

• SPE shall own exclusive rights, including any and all intellectual property rights, and shall be entitled to the unrestricted use of Submissions for any purpose, commercial or otherwise, without acknowledgment or additional compensation to you.

In the event applicable law operates to prevent such assignment described above, or otherwise prevents SPE from becoming the sole owner of any such Submissions, you agree to grant to SPE, and this provision shall be effective as granting to SPE, (with unfettered rights of assignment) a perpetual, worldwide, paid-in-full, nonexclusive right (including any moral rights) and license to make, use, sell, reproduce, modify, adapt, publish, translate, create derivative works from, distribute, communicate to the public, perform and display the Submissions (in whole or in part) worldwide and or to incorporate it in other works in any form, media, or technology now known or later developed, for the full term of any rights that may exist in any such Submissions.

By making Submissions, you represent that (i) you have full power and authority to make the assignment and license set forth above, (ii) the Submissions do not infringe the intellectual property rights of any third party, and (iii) SPE shall be free and have the right to use, assign, modify, edit, alter, adapt, distribute, dispose, promote, display, and transmit the Submissions, or reproduce them, in whole or in part, without compensation, notification, or additional consent from you or from any third party.

Essentially, the above states that Sony takes ownership of your portfolio material when you apply for the job. If you are submitting samples of work you have done for other companies, Sony wants you to assign the rights to them. You clearly don't have the authority to do that for work you don't own, so that means that you are not legally allowed to show Sony work you've done for other companies. Sort of defeats the purpose of a submission portfolio, doesn't it?

What's clearly disturbing though, is that any original work in your portfolio becomes their property. This does not depend on whether they hire you or not, they get ownership because you applied.

How absurd is this? It means that legally, you could not take your own work and use it to apply to another company later, as it would now be owned by Sony. Furthermore, what right does Sony have to take ownership of your work without payment? And of course, it's not enough that Sony owns it, they list all the ways that they can use and mutilate your work "without compensation, notification, additional consent from you or from any third party."

Sony's lawyers have been overzealous here. It means that nobody should be applying for these jobs, as you can't show them your work for others and shouldn't show them your personal work.

Undoubtedly, someone will say it's just boilerplate. Sony would never exercise these rights, they're just trying to protect themselves. People sign what they have to in order to get work. But it remains a legal document unless it is successfully challenged in court, and that takes time and money.

Imagine this scenario. I may hire you, but before you apply, I say you have to sign an I.O.U. for $100,000. I have no intention of ever collecting. It's just a formality. But the fact remains that by applying to work for me, you've given me the right to collect $100,000 from you. Would you want that hanging over your head? Would you want to hire a lawyer and go to court if I decide to collect? Isn't it doubly absurd if I don't hire you and never pay you a nickel but still want the $100,000?

Sony needs to rewrite their terms of use.

Saturday, November 10, 2012

What's Wrong With This Picture?

That's Mark Andrews, the final director of Pixar's Brave. He is the recipient of the Global Scottish Thistle Award, for "those who have helped to put Scotland on the world stage." So far as I know, Andrews had nothing to do with setting the film in Scotland and Visit Scotland, the organization that gave him the award, seems to have no knowledge of Brenda Chapman, the film's original director.

Thursday, November 08, 2012

Is Hasbro Next?

The Beat is reporting that Disney is in talks with Hasbro, which currently holds the toy licenses for Star Wars and the Marvel characters as well as owning Toy Story's Mr. Potato Head. Here is a list of the other things that Hasbro owns or licenses. While this could be as simple as a renegotiation of toy licenses, given Robert Iger's history it may be an indication that Hasbro is Disney's next purchase.

Sunday, November 04, 2012

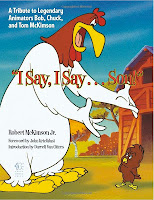

I Say, I Say...Son!

While many gaps in animation history have been filled in the last 40 years, gaps remain. That's why any new book that fills in some blanks is to be celebrated. While Warner Bros. cartoons and certain of the directors have been covered relatively well, Bob McKimson has been present only intermittently in writings about the studio. Part of the reason is that he died just as animation history was moving into high gear and partially because he never attracted the critical or fan attention that directors like Chuck Jones did.

This book (with excerpts available at the link), written by McKimson's son, Robert Jr, also covers McKimson's brothers Tom and Chuck, both of whom also contributed to Warner Bros. cartoons in the areas of character design and animation respectively.

While the book covers their entire careers, it doesn't go into as much depth as I would have liked. Given that the author was a relative, I wish there had been more about the brothers as people. I didn't get a good picture of their personalities or their relationship.

As well, the book isn't specific enough about some of the work. Chuck McKimson animated for Bob for several years in the post-war period, but no scenes are identified as his work and there is no discussion about how his animation differed, if at all, from his brother's. While the author is right to point out that Bob McKimson was the only Warner Bros. director who continued to animate on his cartoons, with the exception of The Hole Idea (animated entirely by the director due to the studio shutting down temporarily), there are no animation scenes identified from his years as a director.

There's also no discussion of the evolution of the McKimson brothers' art over time. It's clear from the illustrations that their styles changed over the years, and not always for the better. By the 1950's, there's a tightness to some of Bob McKimson's drawings that compare unfavourably to his work during the 1940s. In the '50s, he had a tendency to draw arms and legs on characters like Bugs Bunny with parallel lines, causing the character to flatten out considerably. The liveliness and energy that he gave to Bugs in earlier years seems to have dissipated.

The best parts of the book are the illustrations, which cover a range of fields: animation, comics, colouring books and publicity artwork. The McKimson brothers had a definite influence on the look of Warner Bros. cartoons, especially in the years before the end of World War II. Bob and Tom were major contributors to the Bob Clampett unit and Bob McKimson was arguably the main artistic influence on the look of Bugs Bunny, first for Tex Avery and later for Clampett. As a director, Bob McKimson is probably best known for Foghorn Leghorn and the Tasmanian Devil, who appeared in his cartoons exclusively.

The McKimson brothers are certainly worthy of a book and this one is a start. As it is the best currently available, it is worth having, but there's a lot more to be said about the brothers and I hope that this isn't the last we'll read of them.

This book (with excerpts available at the link), written by McKimson's son, Robert Jr, also covers McKimson's brothers Tom and Chuck, both of whom also contributed to Warner Bros. cartoons in the areas of character design and animation respectively.

While the book covers their entire careers, it doesn't go into as much depth as I would have liked. Given that the author was a relative, I wish there had been more about the brothers as people. I didn't get a good picture of their personalities or their relationship.

As well, the book isn't specific enough about some of the work. Chuck McKimson animated for Bob for several years in the post-war period, but no scenes are identified as his work and there is no discussion about how his animation differed, if at all, from his brother's. While the author is right to point out that Bob McKimson was the only Warner Bros. director who continued to animate on his cartoons, with the exception of The Hole Idea (animated entirely by the director due to the studio shutting down temporarily), there are no animation scenes identified from his years as a director.

There's also no discussion of the evolution of the McKimson brothers' art over time. It's clear from the illustrations that their styles changed over the years, and not always for the better. By the 1950's, there's a tightness to some of Bob McKimson's drawings that compare unfavourably to his work during the 1940s. In the '50s, he had a tendency to draw arms and legs on characters like Bugs Bunny with parallel lines, causing the character to flatten out considerably. The liveliness and energy that he gave to Bugs in earlier years seems to have dissipated.

The best parts of the book are the illustrations, which cover a range of fields: animation, comics, colouring books and publicity artwork. The McKimson brothers had a definite influence on the look of Warner Bros. cartoons, especially in the years before the end of World War II. Bob and Tom were major contributors to the Bob Clampett unit and Bob McKimson was arguably the main artistic influence on the look of Bugs Bunny, first for Tex Avery and later for Clampett. As a director, Bob McKimson is probably best known for Foghorn Leghorn and the Tasmanian Devil, who appeared in his cartoons exclusively.

The McKimson brothers are certainly worthy of a book and this one is a start. As it is the best currently available, it is worth having, but there's a lot more to be said about the brothers and I hope that this isn't the last we'll read of them.

Tuesday, October 30, 2012

Disney Buys Lucas

You can read the details everywhere, so I won't bother with them here.

I have no doubt that Wall Street and investors will see this as a good move, as all they are concerned about is money. However, I'm concerned with artists and Disney's trend is not artist friendly.

Why not? Well, if you happen to be somebody working in computer animation in the San Francisco bay area, there is now one less employer in the market. Pixar and ILM have been charged with collusion, cooperating to make sure that they didn't hire employees from each other. Now they're the same company and they can do what they like with hiring policies and pay scales. As neither studio is union, there is no floor to pay or benefits.

The problem goes beyond that, though. While Disney and Pixar continue to turn out some original films, Pixar has already been strong-armed into making sequels because Disney needs to pay off the purchase price. There will be many, many more Star Wars and Marvel films to pay off those purchases as well.

That takes money and oxygen away from original projects that potentially could become as big as Star Wars or the Marvel Universe. The company is clearly committed to milking existing intellectual property and acquiring more of it than creating new intellectual property. And so much of what Disney is buying is from the last century.

Robert Iger is clearly looking backwards more than forwards.

But don't forget that the Muppets started out as a small troop of puppeteers on local television, Marvel started out as a handful of creators working out of their homes, and George Lucas got turned down by everyone until Alan Ladd, Jr. took a chance (but didn't realize the value of sequel or merchandising rights or he would have kept them). What Robert Iger doesn't see is that great creations don't come from large companies, they come from people committed to their own ideas who work out of basements, garages, warehouses and other out of the way places. Sort of the way Walt Disney started. Remember him?

Which means that while Iger is busy grinding out Muppets, Marvels and Star Wars, the great creations of the 21st century will be happening elsewhere. Seek them out.

I have no doubt that Wall Street and investors will see this as a good move, as all they are concerned about is money. However, I'm concerned with artists and Disney's trend is not artist friendly.

Why not? Well, if you happen to be somebody working in computer animation in the San Francisco bay area, there is now one less employer in the market. Pixar and ILM have been charged with collusion, cooperating to make sure that they didn't hire employees from each other. Now they're the same company and they can do what they like with hiring policies and pay scales. As neither studio is union, there is no floor to pay or benefits.

The problem goes beyond that, though. While Disney and Pixar continue to turn out some original films, Pixar has already been strong-armed into making sequels because Disney needs to pay off the purchase price. There will be many, many more Star Wars and Marvel films to pay off those purchases as well.

That takes money and oxygen away from original projects that potentially could become as big as Star Wars or the Marvel Universe. The company is clearly committed to milking existing intellectual property and acquiring more of it than creating new intellectual property. And so much of what Disney is buying is from the last century.

Robert Iger is clearly looking backwards more than forwards.

But don't forget that the Muppets started out as a small troop of puppeteers on local television, Marvel started out as a handful of creators working out of their homes, and George Lucas got turned down by everyone until Alan Ladd, Jr. took a chance (but didn't realize the value of sequel or merchandising rights or he would have kept them). What Robert Iger doesn't see is that great creations don't come from large companies, they come from people committed to their own ideas who work out of basements, garages, warehouses and other out of the way places. Sort of the way Walt Disney started. Remember him?

Which means that while Iger is busy grinding out Muppets, Marvels and Star Wars, the great creations of the 21st century will be happening elsewhere. Seek them out.

Wednesday, October 24, 2012

Is That You, Popeye?

The above was created by artist Lee Romao. You can buy a 7 by 10 inch print of this for $15, as well as well as getting the image on canvas, stationary, or iPhone or iPad skins. Aren't you glad that Genndy Tartakovsky is making the next Popeye feature and not Spielberg or Zemeckis?

(link via Boing Boing)

(link via Boing Boing)

Monday, October 22, 2012

Marvel Comics: The Untold Story

Sean Howe's book Marvel Comics: The Untold Story could just as easily have been subtitled The Never Ending Story. It's never ending as Marvel's fictional characters die, are brought back, change their powers, get replaced, get cloned, make deals with the devil, but still go on and on. It's also never ending because the creators behind these characters leave in disgust, get fired, sue the company and sometimes die on the job.

This book is a warts-and-all telling of the people and business behind the creation of the Marvel universe, known for characters such as Spider-man, the Fantastic Four, Captain America, Iron Man, Thor, the Hulk and the X-Men. While it is only tangentially related to animation, it shares the problems of work-for-hire and the callous way that corporations treat the very people who create the wealth.

For those who haven't followed the comics or the company, this book may be a maddening read, as the cast of fictional and real characters runs into the hundreds. The size of the cast prevents Howe from going into depth on more than a few people, mainly the owners, editors and to a lesser extent, writers. The artists, as usual, get short shrift. Anyone interested in learning more about artists John Buscema, Gene Colan and similar mainstays of the company will be disappointed. The artists are mostly bystanders while the dance of power and money goes on above their heads.

Martin Goodman was a publisher of pulp magazines, a now extinct breed of publications that focused on genre fiction with detectives, cowboys, aviators and similar action-oriented characters. They were named pulps for the cheap wood pulp paper they were printed on. After the success of Superman in Action Comics in the late 1930s, Goodman was convinced to add comic books to his list of publications. Within the first few years, he published The Human Torch (created by Carl Burgos), The Sub-Mariner (created by Bill Everett) and Captain America (created by Joe Simon and Jack Kirby). He hired his wife's cousin, 17 year old Stanley Leiber to work in the comics division and in 1941 when editor Joe Simon left (with Kirby) after Goodman screwed them out of Captain America royalties, Leiber writing under the pseudonym Stan Lee inherited the post of comics editor.

With the exception of his stint in the military during World War II, Lee continued running the division and created nothing of value until 1961. At that point, partnered with Jack Kirby and Steve Ditko, newly successful characters appeared for about a decade. However, both Ditko and Kirby walked away from Lee and Marvel, angry over their lack of control and compensation. Once that happened, Lee spent the next 40 years promoting Marvel and himself but failed to create anything similarly successful. His greatest accomplishment was keeping himself front and center as the ownership changed repeatedly, garnering millions for himself while not lifting a finger as President and Publisher of Marvel to compensate the artists beyond paying them by the page. He even colluded with his competitor, DC Comics, to make sure that freelancers couldn't play the two companies off each other for higher pay.

It's fitting that Disney now owns Marvel as the companies have similarities in their histories. The business people who have taken over both companies after their founders have earned far more than the creative people who built the company in the first place. Eric Ellenbogan, a Marvel executive who lasted just seven months, walked away with a $2.5 million severance package, more money than Jack Kirby made from Marvel in his entire career. That's hardly different than the $140 million in severance that Michael Ovitz walked away from Disney with, more money than all nine old men made over 40 years. John Lasseter is rapidly becoming another Stan Lee, agreeing to corporate moves he formerly disdained (like sequels) and becoming a kibitzer of other people's work rather than remaining a creator himself. For both companies, the '90s were an anomaly where artists actually shared in the money their work generated. Marvel went bankrupt and Disney abandoned drawn animation and the artists who created it. In both cases, the good times didn't last.

The book contains just two illustrations: an ad for the first issue of Marvel Comics and a photograph of Stan Lee and Jack Kirby in 1965. Undoubtedly, the publisher didn't want to deal with Disney's well-known reluctance to grant the rights to images it owns (see the delay in Amid Amidi's biography of Ward Kimball). However, Howe has a tumblr blog which includes many illustrations and documents that should have appeared. Somehow print attracts the copyright cops while the web escapes unscathed, more proof that the copyright laws are dysfunctional in the digital age.

Anyone who aspires to work for a leading comics or animation company and thinks they'll be entering a magic kingdom where creativity reigns supreme and the fun never stops should read this book. Large media corporations share many of Marvel's problems. Artists are routinely taken advantage of, and the more artists realize this on the way in, the less likely they are to be disappointed.

This book is a warts-and-all telling of the people and business behind the creation of the Marvel universe, known for characters such as Spider-man, the Fantastic Four, Captain America, Iron Man, Thor, the Hulk and the X-Men. While it is only tangentially related to animation, it shares the problems of work-for-hire and the callous way that corporations treat the very people who create the wealth.

For those who haven't followed the comics or the company, this book may be a maddening read, as the cast of fictional and real characters runs into the hundreds. The size of the cast prevents Howe from going into depth on more than a few people, mainly the owners, editors and to a lesser extent, writers. The artists, as usual, get short shrift. Anyone interested in learning more about artists John Buscema, Gene Colan and similar mainstays of the company will be disappointed. The artists are mostly bystanders while the dance of power and money goes on above their heads.

Martin Goodman was a publisher of pulp magazines, a now extinct breed of publications that focused on genre fiction with detectives, cowboys, aviators and similar action-oriented characters. They were named pulps for the cheap wood pulp paper they were printed on. After the success of Superman in Action Comics in the late 1930s, Goodman was convinced to add comic books to his list of publications. Within the first few years, he published The Human Torch (created by Carl Burgos), The Sub-Mariner (created by Bill Everett) and Captain America (created by Joe Simon and Jack Kirby). He hired his wife's cousin, 17 year old Stanley Leiber to work in the comics division and in 1941 when editor Joe Simon left (with Kirby) after Goodman screwed them out of Captain America royalties, Leiber writing under the pseudonym Stan Lee inherited the post of comics editor.

With the exception of his stint in the military during World War II, Lee continued running the division and created nothing of value until 1961. At that point, partnered with Jack Kirby and Steve Ditko, newly successful characters appeared for about a decade. However, both Ditko and Kirby walked away from Lee and Marvel, angry over their lack of control and compensation. Once that happened, Lee spent the next 40 years promoting Marvel and himself but failed to create anything similarly successful. His greatest accomplishment was keeping himself front and center as the ownership changed repeatedly, garnering millions for himself while not lifting a finger as President and Publisher of Marvel to compensate the artists beyond paying them by the page. He even colluded with his competitor, DC Comics, to make sure that freelancers couldn't play the two companies off each other for higher pay.

It's fitting that Disney now owns Marvel as the companies have similarities in their histories. The business people who have taken over both companies after their founders have earned far more than the creative people who built the company in the first place. Eric Ellenbogan, a Marvel executive who lasted just seven months, walked away with a $2.5 million severance package, more money than Jack Kirby made from Marvel in his entire career. That's hardly different than the $140 million in severance that Michael Ovitz walked away from Disney with, more money than all nine old men made over 40 years. John Lasseter is rapidly becoming another Stan Lee, agreeing to corporate moves he formerly disdained (like sequels) and becoming a kibitzer of other people's work rather than remaining a creator himself. For both companies, the '90s were an anomaly where artists actually shared in the money their work generated. Marvel went bankrupt and Disney abandoned drawn animation and the artists who created it. In both cases, the good times didn't last.

The book contains just two illustrations: an ad for the first issue of Marvel Comics and a photograph of Stan Lee and Jack Kirby in 1965. Undoubtedly, the publisher didn't want to deal with Disney's well-known reluctance to grant the rights to images it owns (see the delay in Amid Amidi's biography of Ward Kimball). However, Howe has a tumblr blog which includes many illustrations and documents that should have appeared. Somehow print attracts the copyright cops while the web escapes unscathed, more proof that the copyright laws are dysfunctional in the digital age.

Anyone who aspires to work for a leading comics or animation company and thinks they'll be entering a magic kingdom where creativity reigns supreme and the fun never stops should read this book. Large media corporations share many of Marvel's problems. Artists are routinely taken advantage of, and the more artists realize this on the way in, the less likely they are to be disappointed.

The Rabbi's Cat

LCHDR by azmovies

This film screened in Toronto, presented by the Toronto Jewish Film Festival and The Beguiling.

The film is based on a series of comics by Joann Sfar. Set in Algiers, where Sfar's own family once resided, it has a large cast of distinctive characters. The widowed Rabbi has a daughter with her own circle of friends. A cousin who travels with a lion pays a visit. The rabbi is friends with a Muslim cleric with the same last name. A Russian artist, a White Russian, an African waitress, the rabbi's mentor and his student are other well-developed supporting characters.

While not revealing too much of the plot, several of the characters go on a meandering road trip searching for a utopia that turns out to be a false one. The irony is that the searchers are an ad hoc society closer to utopia than the place they are seeking, in that they are of varying religions, nationalities, races and species and get along, using words and art as their means of communication, not weapons.

The design work in the film is stronger than the animation. There are several backgrounds that are frame-worthy. The characters are rich and a pleasure to spend time with as they discuss life, philosophy and more mundane subjects. However, the film lacks structure and narrative drive, as do Sfar's original comics. The film evokes directors like Renoir and McCarey in its focus on people living and its rejection of melodrama.

I have to say that France is producing some of the more interesting animated features I've seen in the last several years. When I attended a presentation by Gobelins, they mentioned that France releases about ten animated features a year. While I'm sure that some of them are aimed squarely at children, it also includes films like Persepolis, Le Tableau and The Rabbi's Cat, which can be enjoyed by children, but speak to more adult concerns. The last two are being distributed by GKIDS and will be screened in November in Los Angeles in order to be submitted for the Oscars.

Sunday, October 21, 2012

Funny Feet: The Art of Eccentric Dance

I've always loved dance animation. Whether it is Mickey in Thru the Mirror or Donald in Mr. Duck Steps Out or the dancing in Rooty Toot Toot, when expressive movement joins with music, you get an energy that leaves ordinary animation in the dust. Dick Lundy, Les Clark, Ken Harris, Preston Blair, Ward Kimball, and Pat Matthews are just some of the animators with a genuine flair for dance.

Animated dance built on what was happening in live action films, and that was built on what had been done in Vaudeville and the English music hall. Chaplin, Keaton, Stan Laurel, Groucho Marx, and James Cagney all used dance in their stage performances. Fred Astaire, Gene Kelly, Ray Bolger, Buddy Ebsen, and the Nicholas Brothers were all influenced by the same tradition.

Betsy Baytos has worked as an animator and dancer and is making a documentary called Funny Feet: The Art of Eccentric Dance. Her promo is below:

She's using Kickstarter to fund a trip to England to research music hall performers who fall into the eccentric dance category.

In addition to interviewing performers for the last 20 years, she has also interviewed artists Chuck Jones, Frank Thomas & Ollie Johnston, Ward Kimball, Myron Waldman (Betty Boop/Popeye) , Joe Barbera, Joe Grant and Al Hirschfeld (NY Times caricaturist).

Here's a clip from a Buster Keaton two reeler for Columbia. Keaton and Columbia were not a good fit. The studio was much more at home with the lowbrow knockabout of The Three Stooges than it was with Keaton's deadpan irony. Elsie James, the woman in this clip, is a pretty crude performer with a tendency to mug. However, I'm including this clip because after the three minute mark, there's about 20 seconds of sublime dance by Keaton, where he transcends Columbia's limited view of comedy.

I'm excited about the subject matter of Baytos's documentary and looking forward to seeing it. Read more about it on her Kickstarter page.

Animated dance built on what was happening in live action films, and that was built on what had been done in Vaudeville and the English music hall. Chaplin, Keaton, Stan Laurel, Groucho Marx, and James Cagney all used dance in their stage performances. Fred Astaire, Gene Kelly, Ray Bolger, Buddy Ebsen, and the Nicholas Brothers were all influenced by the same tradition.

Betsy Baytos has worked as an animator and dancer and is making a documentary called Funny Feet: The Art of Eccentric Dance. Her promo is below:

She's using Kickstarter to fund a trip to England to research music hall performers who fall into the eccentric dance category.

In addition to interviewing performers for the last 20 years, she has also interviewed artists Chuck Jones, Frank Thomas & Ollie Johnston, Ward Kimball, Myron Waldman (Betty Boop/Popeye) , Joe Barbera, Joe Grant and Al Hirschfeld (NY Times caricaturist).

Here's a clip from a Buster Keaton two reeler for Columbia. Keaton and Columbia were not a good fit. The studio was much more at home with the lowbrow knockabout of The Three Stooges than it was with Keaton's deadpan irony. Elsie James, the woman in this clip, is a pretty crude performer with a tendency to mug. However, I'm including this clip because after the three minute mark, there's about 20 seconds of sublime dance by Keaton, where he transcends Columbia's limited view of comedy.

I'm excited about the subject matter of Baytos's documentary and looking forward to seeing it. Read more about it on her Kickstarter page.

Thursday, October 18, 2012

Animation on TCM Reminder

If you receive Turner Classic Movies, remember that this Sunday, October 21, they will be screening an evening of animation co-hosted by Jerry Beck of Cartoon Brew. Films include the two Fleischer features Gulliver's Travels and Mr. Bug Goes to Town; a selection of UPA Jolly Frolic cartoons; a selection of silent animation provided by historian Tom Stathes; and The Adventures of Prince Achmed, which is the oldest surviving animated feature as well as the first animated feature directed by a woman, Lotte Reineger. You can find the complete schedule here and Beck has posted artwork associated with Gulliver and Mr. Bug on his site.

If you are interested in hearing about how Beck connected up with TCM and learning more about the early days of film collecting, you can hear him on a podcast called The Commentary Track.

If you are interested in hearing about how Beck connected up with TCM and learning more about the early days of film collecting, you can hear him on a podcast called The Commentary Track.

Sunday, October 07, 2012

More Loomis

Sections include line, tone, colour, and creating ideas. It is by far the thickest of Loomis's books and before this reprinting, copies sold for over $100.

Titan Books will reprint Fun With a Pencil next April, Loomis's most basic how to draw book. All that will remain, should Titan continue, will be Three Dimensional Drawing, an expanded version of Successful Drawing which they have already reprinted, and The Eye of the Painter and the Elements of Beauty, a book published after Loomis's death. Used copies of that start at $141.

Friday, October 05, 2012

Manolito's Dream

I wrote about Txesco Montalt's work before, and here is a short that he created with Mayte Sanchez Solis. Both of them worked on Pocoyo, one of the few pre-school shows I can watch without falling asleep. Like Txesco's earlier work, it synchs beautifully to the soundtrack and while done in Flash, has lots of subtle shape-changing that gives it wonderful flexibility.

I'm also in love with the simplicity of the design.

The two are partnered in a company called Alla Kinda, and even their logo

exudes charm. Their site is worth checking out.

I'm also in love with the simplicity of the design.

The two are partnered in a company called Alla Kinda, and even their logo

exudes charm. Their site is worth checking out.

Tuesday, September 25, 2012

Ottawa Festival Report

My visit to the Ottawa International Animation Festival got off to a bad

start. I usually walk from the bus station to the hotel, but it was

pouring rain when I arrived. As the walk would have been a half hour, I

would have been thoroughly soaked, so I was forced to take a cab.

The wireless at my hotel was not working when I arrived, which was frustrating. The first program I attended was the International Student Showcase, which was a unrelieved depression and boredom. It may be the choice of films or maybe students are actually this depressed, pretentious and boring, but I was contemplating never coming back to the festival during this screening.

Fortunately, this was the low point and things rapidly improved. The next thing I attended was Amid Amidi's presentation on Ward Kimball, a teaser for his forthcoming book Full Steam Ahead: The Life and Art of Ward Kimball. Amidi covered things I didn't know about Kimball's childhood and his artistic evolution. Kimball's father had repeated business failures and seemingly moved the family to a new location after every one. It prevented Kimball from forming long-term friendships and made drawing more attractive as it was one of the few areas of his life that Kimball could control. Amidi talked about the influence of T. Hee on Kimball, moving Kimball's art more towards simplified design. The talk was illustrated by unpublished paintings, drawings and home movies. Amidi has the cooperation of the Kimball family, including access to the journals that Kimball kept during his time at Disney, so he had access to a rich source of material not common in other Disney books. I pre-ordered the book as soon as Amazon listed it, and I am even more anxious to read it after seeing this presentation.

I started Saturday seeing part of an interview with Elliot Cowan conducted by Richard O'Connor. Cowan is at work on an independent animated feature starring his characters Boxhead and Roundhead, the star of several shorts. It's great that so many animators are tackling the challenge of a feature either solo or with small crews. It's more likely we'll see artistic and thematic growth in these films than in mainstream animated features.

That was followed by a panel discussion of professional etiquette for job seekers and people pitching in animation. I've attended several of these panels and they all hit the same notes: research who you're talking to and make sure you're a good fit, be brief, get to the point, and network like crazy.

Ralph Bakshi's talk was easily a highlight. Unfortunately, it was not well-attended and people missed a tremendous opportunity to hear an important figure. Bakshi readily confessed to the shortcomings of his films, but stressed the conditions they were made under. He couldn't afford pencil tests and there was no room for retakes. He talked about the incessant battles over money, ratings, distribution, etc. His attitude has always been that it's better to say something in a flawed way than to say nothing new in a slick package. By coincidence, I was re-reading Sam Fuller's autobiography A Third Face during the festival and I realized that Bakshi is animation's Fuller. Fuller stuck with low budgets in order to have creative freedom (though I suppose that Bakshi didn't do that by choice), and Fuller's style was always blunt and direct. There are similarities between Fuller's films Shock Corridor and The Naked Kiss and Bakshi's films set in New York.

Bakshi is currently doing shorts for YouTube. Here is Trickle Dickle Down. The animation is repurposed from Coonskin, which caused Jerry Beck to reject running it on Cartoon Brew. Bakshi was very vocal in his disagreement over this, stating that the message was more important than the re-use.

Following Bakshi's talk, I caught up with Paranorman, which I had missed in theatres. Made by Laika, the company behind Coraline, I actually liked it better than their first feature. While I felt the designs could have been more attractive and that the second act seemed padded, the film worked and had strong themes. The fear of those who are different and the mob descent into violence are themes that are as relevant to the film's supernatural world as they are to international politics.

I only saw one shorts competition this year. These programs are always a mixed bag and all you can hope for are enough films you like to make the program worthwhile. Films I enjoyed in this program included I Am Tom Moody by Ainslie Henderson, Melissa by Cesar Cabral, Pythagasaurus by Peter Peake of Aardman, Night of the Loving Dead by Anna Humphries, Una Fortiva Lagrima by Carlo Vogele (using a 1904 recording by Enrico Caruso), and The People Who Never Stop by Florien Piento.

Due to arriving on Friday and various schedule conflicts, I only got to see one feature in competition, Le Tableau, directed by Jean-Francois Laguionie. It is set inside an unfinished painting, where the figures form a class system based on their level of completion. While this film also had a meandering second act, it dealt with fascism, ethnic cleansing, the search for God and God's responsibility toward his creations. The film combines cel-shaded 3D with painterly 2.5D backgrounds and while I could think of ways that characters could have been more developed, I was still highly impressed with the look and the thoughtfulness of the film. See it if you get the chance.

I regret missing Arrugas, directed by Ignacio Ferreras, a feature set in a retirement home and which won the grand prize at the festival. If anyone has seen it, please comment below.

Sunday, I started with the Barry Purves retrospective. Purves, a brilliant stop motion animator, introduced his work and then returned to answer questions at the end. Besides running clips from his TV work, he ran Next, Screen Play, Riggoletto, Achilles and Gilbert and Sullivan. Purves is clearly in love with opera and operatic voices. Riggoletto and Gilbert and Sullivan are built entirely around them. However, I wonder if the music and singing are too broad for the intimacy of film. On stage, the audience is a distance from the action and there is no cutting or close-ups possible. When the audience is only inches from a character's face, the operatic delivery often overpowers the visuals. Purves would be horrified at the idea of redubbing his films, I'm sure, but I wonder how they would play with more intimate arrangements and singing. None of this takes away from his mastery of performance, though.

I ended my festival with the screening of children's films. Every year I look forward to this, as the films are the antithesis of most of the shorts in the festival. They are bright, funny, well-paced and are clearly concerned with how the audience will receive them. While all the films were worth watching, my favourites were Stick Up For Your Friends by Anthony Dusko, My Strange Grandfather by Dina Velikovskaya, From Point A to Point Z by Karl Staven, Why Do We Put Up With Them? by David Chai and Thank You by Pendleton Ward and Thomas Herpich. I was pleased to see that two excellent films were from Toronto: The Fox and the Chickadee by Evan DeRushie and Beethoven's Wig by Alex Hawley and Denny Silverthorne of Smiley Guy Studios.

The wireless at my hotel was not working when I arrived, which was frustrating. The first program I attended was the International Student Showcase, which was a unrelieved depression and boredom. It may be the choice of films or maybe students are actually this depressed, pretentious and boring, but I was contemplating never coming back to the festival during this screening.

Fortunately, this was the low point and things rapidly improved. The next thing I attended was Amid Amidi's presentation on Ward Kimball, a teaser for his forthcoming book Full Steam Ahead: The Life and Art of Ward Kimball. Amidi covered things I didn't know about Kimball's childhood and his artistic evolution. Kimball's father had repeated business failures and seemingly moved the family to a new location after every one. It prevented Kimball from forming long-term friendships and made drawing more attractive as it was one of the few areas of his life that Kimball could control. Amidi talked about the influence of T. Hee on Kimball, moving Kimball's art more towards simplified design. The talk was illustrated by unpublished paintings, drawings and home movies. Amidi has the cooperation of the Kimball family, including access to the journals that Kimball kept during his time at Disney, so he had access to a rich source of material not common in other Disney books. I pre-ordered the book as soon as Amazon listed it, and I am even more anxious to read it after seeing this presentation.

I started Saturday seeing part of an interview with Elliot Cowan conducted by Richard O'Connor. Cowan is at work on an independent animated feature starring his characters Boxhead and Roundhead, the star of several shorts. It's great that so many animators are tackling the challenge of a feature either solo or with small crews. It's more likely we'll see artistic and thematic growth in these films than in mainstream animated features.

That was followed by a panel discussion of professional etiquette for job seekers and people pitching in animation. I've attended several of these panels and they all hit the same notes: research who you're talking to and make sure you're a good fit, be brief, get to the point, and network like crazy.

Ralph Bakshi

Bakshi is currently doing shorts for YouTube. Here is Trickle Dickle Down. The animation is repurposed from Coonskin, which caused Jerry Beck to reject running it on Cartoon Brew. Bakshi was very vocal in his disagreement over this, stating that the message was more important than the re-use.

Following Bakshi's talk, I caught up with Paranorman, which I had missed in theatres. Made by Laika, the company behind Coraline, I actually liked it better than their first feature. While I felt the designs could have been more attractive and that the second act seemed padded, the film worked and had strong themes. The fear of those who are different and the mob descent into violence are themes that are as relevant to the film's supernatural world as they are to international politics.

I only saw one shorts competition this year. These programs are always a mixed bag and all you can hope for are enough films you like to make the program worthwhile. Films I enjoyed in this program included I Am Tom Moody by Ainslie Henderson, Melissa by Cesar Cabral, Pythagasaurus by Peter Peake of Aardman, Night of the Loving Dead by Anna Humphries, Una Fortiva Lagrima by Carlo Vogele (using a 1904 recording by Enrico Caruso), and The People Who Never Stop by Florien Piento.

Due to arriving on Friday and various schedule conflicts, I only got to see one feature in competition, Le Tableau, directed by Jean-Francois Laguionie. It is set inside an unfinished painting, where the figures form a class system based on their level of completion. While this film also had a meandering second act, it dealt with fascism, ethnic cleansing, the search for God and God's responsibility toward his creations. The film combines cel-shaded 3D with painterly 2.5D backgrounds and while I could think of ways that characters could have been more developed, I was still highly impressed with the look and the thoughtfulness of the film. See it if you get the chance.

I regret missing Arrugas, directed by Ignacio Ferreras, a feature set in a retirement home and which won the grand prize at the festival. If anyone has seen it, please comment below.

Barry Purves

Sunday, I started with the Barry Purves retrospective. Purves, a brilliant stop motion animator, introduced his work and then returned to answer questions at the end. Besides running clips from his TV work, he ran Next, Screen Play, Riggoletto, Achilles and Gilbert and Sullivan. Purves is clearly in love with opera and operatic voices. Riggoletto and Gilbert and Sullivan are built entirely around them. However, I wonder if the music and singing are too broad for the intimacy of film. On stage, the audience is a distance from the action and there is no cutting or close-ups possible. When the audience is only inches from a character's face, the operatic delivery often overpowers the visuals. Purves would be horrified at the idea of redubbing his films, I'm sure, but I wonder how they would play with more intimate arrangements and singing. None of this takes away from his mastery of performance, though.

I ended my festival with the screening of children's films. Every year I look forward to this, as the films are the antithesis of most of the shorts in the festival. They are bright, funny, well-paced and are clearly concerned with how the audience will receive them. While all the films were worth watching, my favourites were Stick Up For Your Friends by Anthony Dusko, My Strange Grandfather by Dina Velikovskaya, From Point A to Point Z by Karl Staven, Why Do We Put Up With Them? by David Chai and Thank You by Pendleton Ward and Thomas Herpich. I was pleased to see that two excellent films were from Toronto: The Fox and the Chickadee by Evan DeRushie and Beethoven's Wig by Alex Hawley and Denny Silverthorne of Smiley Guy Studios.

Sunday, September 23, 2012

Ottawa International Animation Fest Winners

JUNKYARD WINS BEST SHORT, ARRUGAS SELECTED BEST

FEATURE, AT OTTAWA INTERNATIONAL ANIMATION

FESTIVAL

OTTAWA (September 23, 2012) – The Ottawa International Animation Festival (OIAF) came to an end Sunday, with closing ceremonies held at the National Arts Centre. Organizers announced the winners of the official competition during the ceremonies.

This year’s event, held September 19th-23rd, was a tremendous success with packed screenings, sold out workshops, high profile networking events such at the Television Animation Conference (TAC) and a strong weekend of professional development.

The OIAF is a major international film event that attracts 1500 industry pass holders from across Canada and around the world with a total attendance of close to 30,000. Although the final numbers are not officially in, there are strong indications that this year’s Festival reached its highest attendance to date.

The 2012 international jury for Short Program, Student and Commissioned Films included: Mike Fallows (USA), J.J. Sedelmaier (USA) and Sarah Muller(UK). The international jury for Feature Film Competition and School Showreels included: Barry Purves (UK), Hisko Hulsing (Netherlands) and Izabela Rieben (Switzerland).

The Festival also featured a special jury made up of local kids to select the Best Short Animation Made for Children and the Best Television Animation Made for Children. This year’s kids jury included: Jordan Quayle, Evelyn Abacra, Lucas Kelly, Jakob Boose, Zoe Monogian, Conall Sloan, Eleanor Simonetta, Jacob Cooper, Chantalyne Leonhardt and Lauralee Leonhardt.

List of WinnersNelvana GRAND PRIZE for Best Independent Short AnimationJunkyard– directed by Hisko Hulsing, Netherlands

GRAND PRIZE for Best Animated FeatureArrugas (Wrinkles), directed by Ignacio Ferreras, Spain

Walt Disney GRAND PRIZE for Best Student AnimationI Am Tom Moody– directed by Ainslie Henderson, Edinburgh College of Art, UK

GRAND PRIZE for Best Commissioned AnimationPrimus "Lee Van Cleef" - by Chris Smith, USA

Best Animation School ShowreelSupinfocom (France)

BEST Narrative ShortA Morning Stroll - by Grant Orchard, STUDIO AKA, USA

BEST Experimental/Abstract AnimationRivière au Tonnerre – directed by Pierre Hébert, Canada

Adobe Prize for BEST High School AnimationThe Bean – by Hae Jin Jung, Gyeonggi Art High School, South Korea

Honourable Mention:La Soif Du Monde (Thirsty Frog) – by a Collective: 12 Children, Camera-etc, Belgium

BEST Undergraduate AnimationReizwäsche - by Jelena Walf & Viktor Stickel, Germany

BEST Graduate AnimationBallpit – directed by Kyle Mowat, Sheridan College, Canada

BEST Promotional AnimationRed Bull 'Music Academy World Tour' – by Pete Candeland, Passion Pictures, UK

BEST Music VideoThe First Time I Ran Away - by Joel Trussell, USA

BEST Television Animation for AdultsPortlandia: Zero Rats – by Rob Shaw, USA

BEST Short Animation Made for ChildrenBeethoven’s Wig, directed by Alex Hawley & Denny Silverthorne, Canada

Honourable Mentions:Au Coeur de L’Hiver - directed by Isabelle Favez, Switzerland

Why do we Put up with Them? - directed by David Chai, USA

BEST Television Animation Made for ChildrenRegular Show: Eggscellent - by JC Quintel, Cartoon Network

Honourable Mention:Adventure Time: Jake vs. Me-Mow - by Pendleton Ward, Cartoon Network, USA

The National Film Board of Canada PUBLIC PRIZEIt's Such a Beautiful Day - directed by Don Hertzfeldt, USA

Canadian Film Institute Award for BEST Canadian AnimationNightingales in December, directed by Theodore Ushev, Canada

Honourable MentionsBallpit – directed by Kyle Mowat, Sheridan College, Canada

MacPherson - directed by Martine Chartrand, National Film Board of Canada, Canada

BEST Canadian Student Animation AwardGum - By Noam Sussman, Sheridan College, Canadaa

Honourable MentionsBallpit - By Kyle Mowat, Sheridan College, Canada

Tengri - By Alisi Telengut, Concordia University, Canada

The Ottawa Media Jury AwardFor the best short competition film, as deemed by the local Ottawa Media, consisting of:

-Peter Simpson (Ottawa Citizen)

-Sandra Abma (CBC)

-Fateema Sayani (Ottawa Magazine)

-Denis Armstrong (Ottawa Sun)

I Am Tom Moody– By Ainslie Henderson, Edinburgh College of Art, UK

About the OIAFOIAF 2012 was held September 19-23rd, 2012 in Ottawa. Events at the OIAF included screenings, panels, workshops, parties and the Television Animation Conference. The OIAF is a leading competitive animation film festival, featuring cutting edge programming, catering to industry executives, trend setting artists, students and animation fans. For more information about the OIAF, please visit www.animationfestival.ca.

OTTAWA (September 23, 2012) – The Ottawa International Animation Festival (OIAF) came to an end Sunday, with closing ceremonies held at the National Arts Centre. Organizers announced the winners of the official competition during the ceremonies.

This year’s event, held September 19th-23rd, was a tremendous success with packed screenings, sold out workshops, high profile networking events such at the Television Animation Conference (TAC) and a strong weekend of professional development.

The OIAF is a major international film event that attracts 1500 industry pass holders from across Canada and around the world with a total attendance of close to 30,000. Although the final numbers are not officially in, there are strong indications that this year’s Festival reached its highest attendance to date.

The 2012 international jury for Short Program, Student and Commissioned Films included: Mike Fallows (USA), J.J. Sedelmaier (USA) and Sarah Muller(UK). The international jury for Feature Film Competition and School Showreels included: Barry Purves (UK), Hisko Hulsing (Netherlands) and Izabela Rieben (Switzerland).

The Festival also featured a special jury made up of local kids to select the Best Short Animation Made for Children and the Best Television Animation Made for Children. This year’s kids jury included: Jordan Quayle, Evelyn Abacra, Lucas Kelly, Jakob Boose, Zoe Monogian, Conall Sloan, Eleanor Simonetta, Jacob Cooper, Chantalyne Leonhardt and Lauralee Leonhardt.

List of WinnersNelvana GRAND PRIZE for Best Independent Short AnimationJunkyard– directed by Hisko Hulsing, Netherlands

GRAND PRIZE for Best Animated FeatureArrugas (Wrinkles), directed by Ignacio Ferreras, Spain

Walt Disney GRAND PRIZE for Best Student AnimationI Am Tom Moody– directed by Ainslie Henderson, Edinburgh College of Art, UK

GRAND PRIZE for Best Commissioned AnimationPrimus "Lee Van Cleef" - by Chris Smith, USA

Best Animation School ShowreelSupinfocom (France)

BEST Narrative ShortA Morning Stroll - by Grant Orchard, STUDIO AKA, USA

BEST Experimental/Abstract AnimationRivière au Tonnerre – directed by Pierre Hébert, Canada

Adobe Prize for BEST High School AnimationThe Bean – by Hae Jin Jung, Gyeonggi Art High School, South Korea

Honourable Mention:La Soif Du Monde (Thirsty Frog) – by a Collective: 12 Children, Camera-etc, Belgium

BEST Undergraduate AnimationReizwäsche - by Jelena Walf & Viktor Stickel, Germany

BEST Graduate AnimationBallpit – directed by Kyle Mowat, Sheridan College, Canada

BEST Promotional AnimationRed Bull 'Music Academy World Tour' – by Pete Candeland, Passion Pictures, UK

BEST Music VideoThe First Time I Ran Away - by Joel Trussell, USA

BEST Television Animation for AdultsPortlandia: Zero Rats – by Rob Shaw, USA

BEST Short Animation Made for ChildrenBeethoven’s Wig, directed by Alex Hawley & Denny Silverthorne, Canada

Honourable Mentions:Au Coeur de L’Hiver - directed by Isabelle Favez, Switzerland

Why do we Put up with Them? - directed by David Chai, USA

BEST Television Animation Made for ChildrenRegular Show: Eggscellent - by JC Quintel, Cartoon Network

Honourable Mention:Adventure Time: Jake vs. Me-Mow - by Pendleton Ward, Cartoon Network, USA

The National Film Board of Canada PUBLIC PRIZEIt's Such a Beautiful Day - directed by Don Hertzfeldt, USA

Canadian Film Institute Award for BEST Canadian AnimationNightingales in December, directed by Theodore Ushev, Canada

Honourable MentionsBallpit – directed by Kyle Mowat, Sheridan College, Canada

MacPherson - directed by Martine Chartrand, National Film Board of Canada, Canada

BEST Canadian Student Animation AwardGum - By Noam Sussman, Sheridan College, Canadaa

Honourable MentionsBallpit - By Kyle Mowat, Sheridan College, Canada

Tengri - By Alisi Telengut, Concordia University, Canada

The Ottawa Media Jury AwardFor the best short competition film, as deemed by the local Ottawa Media, consisting of:

-Peter Simpson (Ottawa Citizen)

-Sandra Abma (CBC)

-Fateema Sayani (Ottawa Magazine)

-Denis Armstrong (Ottawa Sun)

I Am Tom Moody– By Ainslie Henderson, Edinburgh College of Art, UK

About the OIAFOIAF 2012 was held September 19-23rd, 2012 in Ottawa. Events at the OIAF included screenings, panels, workshops, parties and the Television Animation Conference. The OIAF is a leading competitive animation film festival, featuring cutting edge programming, catering to industry executives, trend setting artists, students and animation fans. For more information about the OIAF, please visit www.animationfestival.ca.

Thursday, September 20, 2012

100 Years of Chuck Jones

September 21, 2012 is the 100th birthday of Charles Martin Jones, arguably the greatest director of animated shorts in history. While there will be justifiable celebrations of his life and work this day, his career strikes me as a very curious thing. There was a period of brilliance, but there was also a period of decline which lasted much longer.

I've wrote about Jones' career back in the '90s and while my knowledge of Jones has been augmented by many interviews with his co-workers (see Michael Barrier's site for many of these), my opinion has remained constant.

Whatever your opinion of Jones, there are worse ways to spend the day than to watch some of his films.

I've wrote about Jones' career back in the '90s and while my knowledge of Jones has been augmented by many interviews with his co-workers (see Michael Barrier's site for many of these), my opinion has remained constant.

Whatever your opinion of Jones, there are worse ways to spend the day than to watch some of his films.

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)