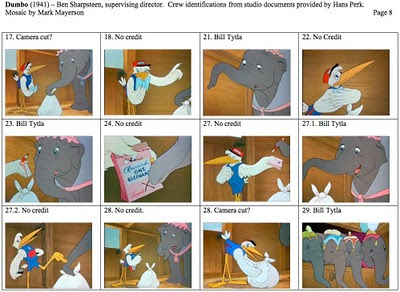

It's a shame that the Dumbo draft that Hans Perk has posted (and it's all available now on his blog) is missing many animator identifications. We can guess that Art Babbitt handled the stork in this sequence, but it remains just a guess. We're fortunate, however, in knowing what Bill Tytla animated in this sequence.

It's a shame that the Dumbo draft that Hans Perk has posted (and it's all available now on his blog) is missing many animator identifications. We can guess that Art Babbitt handled the stork in this sequence, but it remains just a guess. We're fortunate, however, in knowing what Bill Tytla animated in this sequence.This sequence keeps the audience in suspense over Mrs. Jumbo's baby until the baby is finally revealed. It's a two stage reveal, first showing us a cute elephant child and once he sneezes, showing us the ears that are his curse and finally his blessing.

The female elephants are never named onscreen, but are named in the draft. They are Matriarch, Prissy, Catty and Giggles. They are successors to the seven dwarfs in that their names describe their personalities and that they look similar, so must be differentiated by the way they move. Needless to say, Tytla is up to the task.

No explanation is ever given as to where Jumbo, Sr. is. The lack of a male role model for Dumbo or a male counterbalance to the female gossips leaves the role open for Timothy when he later enters the film.

Revision: I think that the use of space in this sequence is very important, and my previous writing about it didn't do it justice. All space on film is constructed. Even if a film is a single shot, there's a frame around it that excludes things. Once you add cutting and camera movement, a film maker is either carving up space or implying relationships by connecting things in space.

It's a cliché, and a useful one, to start a sequence with an establishing shot, showing the audience where everything is. It would be unsurprising to follow shot 11 of the stork looking into the elephant's car with a wide shot showing how many elephants are present and what their spatial relationship is. Instead, the sequence director or the layout artist made the decision to keep the space fragmented. At screen left, we have the four elephants. In the center, we have the stork and Dumbo. On the right, we have Mrs. Jumbo. Center stage is logically where the most important action occurs, and we have the stork concerned with procedure, getting a signature, speaking his poems and singing "Happy Birthday."

Once the stork is gone, Dumbo is center stage. At this point, the left and right become two poles of a magnet. At first, they have an equal attraction for Dumbo. Both sides express obvious pride. In shot 60, Dumbo looks from his mother to the others, and is equally pleased. Interestingly, it is the matriarch, not Mrs. Jumbo, who is the first to actually touch the child. Once his ears are revealed, those on screen left radically change their view.

This results in shot 62, the only shot in the entire sequence to show all the characters at once. Mrs. Jumbo slaps one of the others and removes Dumbo to her side of the screen. For the rest of the sequence, Dumbo is always shown with his mother in the frame. The only other shot with Mrs. Jumbo and the four is 77, where she pulls the pin to shut them away.

The cutting communicates the gap between Mrs. Jumbo and the others. Dumbo begins suspended between the elephants but ends connected spatially to his mother with the four excluded from their space.

The cutting is basic. There are no bravura layouts here, but clearly a lot of thought went into how this key moment -- the revelation of Dumbo's ears and the reaction of the community to it -- was to be staged. That's typical of so much of this film. It doesn't dazzle like Pinocchio or Fantasia, but within its tight budget, the creative choices are invariably effective.