If you have any interest in Fred Moore, you've got to visit Jenny Lerew's blog, where she is posting some great Moore drawings from the collection of James Walker.

Hans Perk continues to post amazing stuff. Recently he put up a drawing of Penny from The Rescuers by Ollie Johnston and the animator draft for The Brave Little Tailor.

Here's a press release about Disney making their films available for downloading. The L.A. Times (registration required) mentions Chicken Little as a forthcoming release in this format.

The Seward Street blog is going dark at the end of June. There's a Ken Harris interview there and lots about Milt Kahl. Get 'em while you can.

Emru Townsend announces a change in frequency and size for the webzine fps. You still have time to subscribe at the old rate.

Finally, John Cawley's Daily Bark for May 30 has some interesting thoughts on what's happening to the director's job in TV animation. When I was directing, I not only thumbnailed the storyboard, I timed the show. I'm aware that the job of director has been fragmented, so that board artists dictate the shot continuity and sheet timers take care of the timing with the director supervising them both. With the increased use of animatics for timing purposes, it seems that other people are now claiming director credit. I would be very interested if anyone currently directing (movies or TV) would leave a comment talking about how these tasks are handled on their productions.

Wednesday, May 31, 2006

Tuesday, May 30, 2006

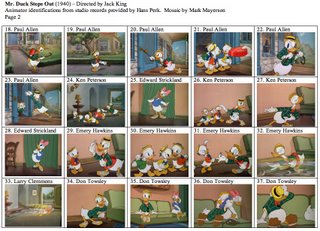

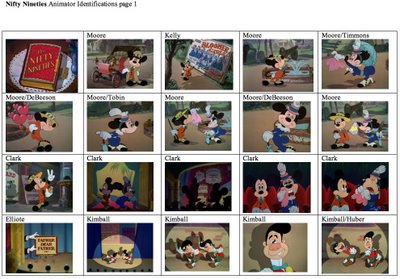

More on Mr. Duck Steps Out

I managed to replace the images in the previous post after discussions with Hans Perk about some of the identifications. Even when you have the drafts, there are mysteries. For instance, shot 73 (and the numbering is mine, not the Disney studio's) is not on the draft. It may be by Ray Patin, who did the surrounding shots, but it may not. And the drafts list shots 93-95 as a single shot. In this case, it's likely that the animation was continuous and it was turned into three shots by changing the camera field during shooting, but we can't really know for sure.

I've admired this cartoon for years, mainly for the dance animation. Looking at it now, I see other things to admire, but I see weaknesses in the cartoon as well.

One of the things I've long noticed about Disney cartoons is their use of space. They don't hesitate to move the camera. If you're aware of what that entailed with cels, backgrounds and a camera stand, you know what an effort it was. Artwork had to be oversized, which made it clumsy to handle, and cranking the compound while shooting made camera work more complicated. For instance, I've only pictured one of the nephews in shot 83, but the camera pans in two directions to include all three of them. Shot 96 has Daisy enter the frame, Donald and Daisy dance through the screens, which vibrate, and then the camera pans to the right to find them on smashed furniture.

Because the Disney studio moves the camera so freely, there's the implication that there's a larger space beyond the frame and we're just seeing a portion of it. Cartoons from other studios move the camera less and in more restricted ways, giving the impression that the characters are confined in an enclosed space.

Another interesting thing about this cartoon is the way it cuts on action. There are more shots here than I realized, even before the pace picks up for the climax. You're not aware of the cutting because the animators make sure that actions continue from one shot to the next, which disguises the cut. This was a hallmark of live action Hollywood films of the time and Disney uses it to advantage. At Warners, the tendency was to cut from one character to another, which was simpler and more economical but didn't give the cartoons the same kind of visual flow.

I do have a couple of problems with this cartoon. While the backgrounds are attractive,

I think that they are overkill. They're not as graphically simple as The Pied Piper of Basin Street, for example, and the highlights, reflections, shadows and graduated tones sometimes make it hard for the characters to read.

My other problem is that the character conflict doesn't pay off properly. The nephews want to get between Donald and Daisy and Donald wants to keep them out of his way. When Donald bests them, they take revenge with the popping corn. But once they stick it to Donald, they don't take advantage of it. They should use Donald's loss of control as a ticket to dancing with Daisy, but instead they opt to play musical instruments, something they could have done at any time without getting into trouble. And Donald's popcorn-powered dancing makes him more attractive in Daisy's eyes, not less. While the nephews want revenge, they actually help Donald and voluntarily step out of his way.

Director Jack King clearly believes in casting animators by sequence. While there are some shots scattered among several animators, most of the sequences are logically cast. Les Clark is better known for his work on Mickey, but his Donald animation is great and he gets the cartoon off to a beautiful start with smart dancing and nice personality touches.

Ken Muse does good work on the nephews and Emery Hawkins does the final shots of the cartoon. King takes advantage of Hawkins' ability to handle broad action.

Shot 46 is almost 14 seconds of continuous dance animation by Paul Allen, somebody who I never was aware of until seeing the draft for this cartoon. He's a very good animator, yet I don't believe that he was ever interviewed or written about. Only Les Clark's work in this cartoon can compare with Allen, who easily outclasses Muse and Lundy here. What a shame we don't know more about him.

One of the things that bothers me about animation history is that the Disney shorts are a historical black hole. There were no credits on them until 1944. Animators who did not work on the features extensively and who left before that date have never received credit for their work. We don't know what films Emery Hawkins and Ken Muse worked on while at Disney. And even animators who stayed beyond 1944, like Paul Allen, spent the better part of their Disney careers without credit. This is one reason why it's so important for these drafts to be published. While it's possible to chart the progress of the Disney studio by looking at the films, it's impossible to see the development of individuals without the drafts.

I've admired this cartoon for years, mainly for the dance animation. Looking at it now, I see other things to admire, but I see weaknesses in the cartoon as well.

One of the things I've long noticed about Disney cartoons is their use of space. They don't hesitate to move the camera. If you're aware of what that entailed with cels, backgrounds and a camera stand, you know what an effort it was. Artwork had to be oversized, which made it clumsy to handle, and cranking the compound while shooting made camera work more complicated. For instance, I've only pictured one of the nephews in shot 83, but the camera pans in two directions to include all three of them. Shot 96 has Daisy enter the frame, Donald and Daisy dance through the screens, which vibrate, and then the camera pans to the right to find them on smashed furniture.

Because the Disney studio moves the camera so freely, there's the implication that there's a larger space beyond the frame and we're just seeing a portion of it. Cartoons from other studios move the camera less and in more restricted ways, giving the impression that the characters are confined in an enclosed space.

Another interesting thing about this cartoon is the way it cuts on action. There are more shots here than I realized, even before the pace picks up for the climax. You're not aware of the cutting because the animators make sure that actions continue from one shot to the next, which disguises the cut. This was a hallmark of live action Hollywood films of the time and Disney uses it to advantage. At Warners, the tendency was to cut from one character to another, which was simpler and more economical but didn't give the cartoons the same kind of visual flow.

I do have a couple of problems with this cartoon. While the backgrounds are attractive,

I think that they are overkill. They're not as graphically simple as The Pied Piper of Basin Street, for example, and the highlights, reflections, shadows and graduated tones sometimes make it hard for the characters to read.

My other problem is that the character conflict doesn't pay off properly. The nephews want to get between Donald and Daisy and Donald wants to keep them out of his way. When Donald bests them, they take revenge with the popping corn. But once they stick it to Donald, they don't take advantage of it. They should use Donald's loss of control as a ticket to dancing with Daisy, but instead they opt to play musical instruments, something they could have done at any time without getting into trouble. And Donald's popcorn-powered dancing makes him more attractive in Daisy's eyes, not less. While the nephews want revenge, they actually help Donald and voluntarily step out of his way.

Director Jack King clearly believes in casting animators by sequence. While there are some shots scattered among several animators, most of the sequences are logically cast. Les Clark is better known for his work on Mickey, but his Donald animation is great and he gets the cartoon off to a beautiful start with smart dancing and nice personality touches.

Ken Muse does good work on the nephews and Emery Hawkins does the final shots of the cartoon. King takes advantage of Hawkins' ability to handle broad action.

Shot 46 is almost 14 seconds of continuous dance animation by Paul Allen, somebody who I never was aware of until seeing the draft for this cartoon. He's a very good animator, yet I don't believe that he was ever interviewed or written about. Only Les Clark's work in this cartoon can compare with Allen, who easily outclasses Muse and Lundy here. What a shame we don't know more about him.

One of the things that bothers me about animation history is that the Disney shorts are a historical black hole. There were no credits on them until 1944. Animators who did not work on the features extensively and who left before that date have never received credit for their work. We don't know what films Emery Hawkins and Ken Muse worked on while at Disney. And even animators who stayed beyond 1944, like Paul Allen, spent the better part of their Disney careers without credit. This is one reason why it's so important for these drafts to be published. While it's possible to chart the progress of the Disney studio by looking at the films, it's impossible to see the development of individuals without the drafts.

Monday, May 29, 2006

Mr. Duck Steps Out

Thanks to Hans Perk for supplying the animator draft for this cartoon. You can see the original studio documentation over at his blog. There's lots of other interesting material there, too, including his company's demo reel.

The mosaics took longer to put together than I expected, so I'll hold off talking about this cartoon until later. It's available on DVD on The Chronological Donald Volume 1.

Sunday, May 28, 2006

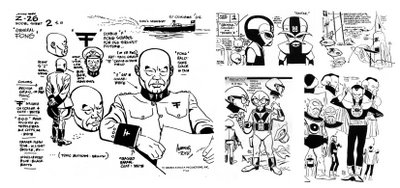

Alex Toth Passes Away

Comic book artist and animation designer Alex Toth passed away on May 27 at the age of 78. Toth was heavily influenced by the Noel Sickles-Milton Caniff school of drawing and began working as an artist in comics in the 1940's. The majority of Toth's comics work was not done on continuing characters, but he did have lengthy stays on Green Lantern in the 1940's and the Disney version of Zorro in the late '50's and the early '60's. Toth's art for romance comics in the '50's was highly respected as was his horror comics work for Warren in the '60's and '70's. He was often referred to as "the artist's artist."

Comic book artist and animation designer Alex Toth passed away on May 27 at the age of 78. Toth was heavily influenced by the Noel Sickles-Milton Caniff school of drawing and began working as an artist in comics in the 1940's. The majority of Toth's comics work was not done on continuing characters, but he did have lengthy stays on Green Lantern in the 1940's and the Disney version of Zorro in the late '50's and the early '60's. Toth's art for romance comics in the '50's was highly respected as was his horror comics work for Warren in the '60's and '70's. He was often referred to as "the artist's artist."

His work in animation was done entirely for television. He started on Clutch Cargo and Space Angel and later moved over to Hanna-Barbera, where he was a designer and sometimes storyboard artists for shows such as Jonny Quest, Space Ghost, The Herculoids, and Super Friends. His work influenced later animation designers and comic book artists such as Bruce Timm, Darwyn Cooke and Steve Rude.

A website devoted to Toth's work can be found here.

Saturday, May 27, 2006

More NYIT Memories

Here, courtesy of John Celestri, are more memories of his time spent at the New York Institute of Technology's animation studio.

JOHN’S BLOG MEMORIES OF NYIT: PART 2

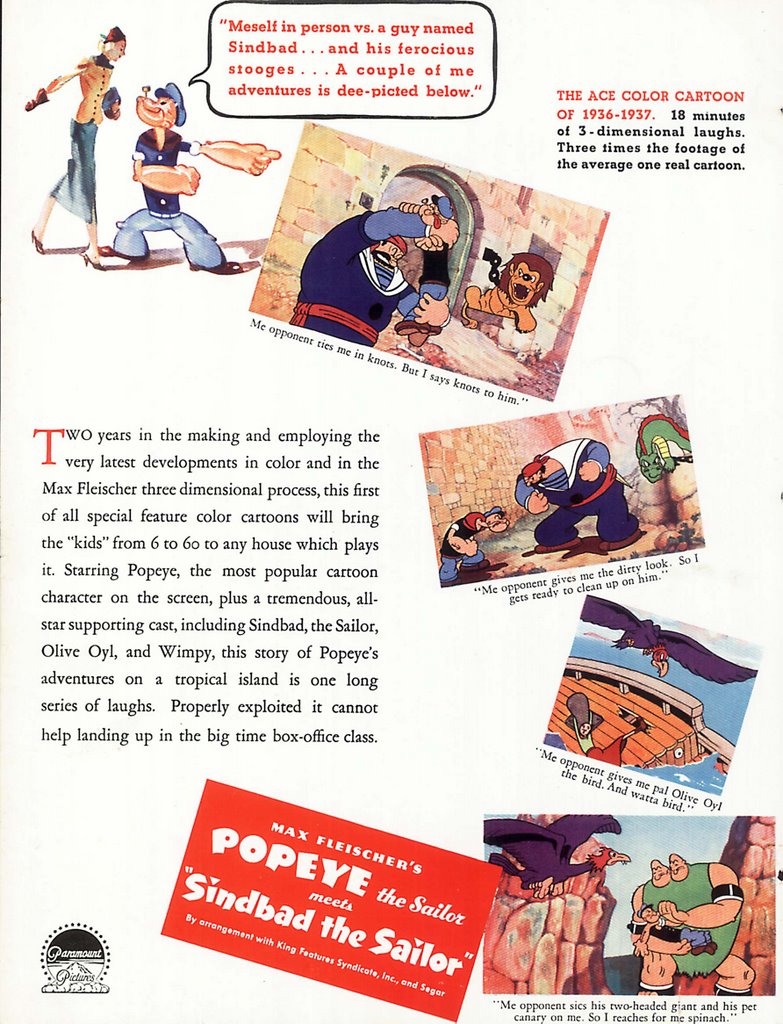

Growing up in Brooklyn during the 1950s, my childhood was full of day-and-night dreams of being powerful like Popeye, Mighty Mouse, and Superman. Oh, what I wouldn’t have given to be able to fly through the air, leap over buildings in a single bound, or be able to pound the neighborhood bully by simple swallowing a mouthful of spinach.

These fantasies were fueled by images I’d seen in the old Terrytoons and Fleischer/Paramount cartoons broadcasted over the local TV airwaves. From the ages of 5 through 12, I was glued to the screen of my family’s old black and white Sylvania, soaking it all in. And when I wasn’t watching Popeye, Mighty Mouse, or Superman cartoons, I was reading their comic books and copying their images onto whatever paper I could find, using whatever pencils I could get from my father, who was a mechanical draftsman.

It was at NYIT that I met some of the artists who created those images of power---power I so desperately wanted to have coursing through my tiny, childhood muscles.

When I first started working at NYIT, I expected to meet animators, but I didn’t realize they were responsible for some of my most cherished childhood fantasies. I was just excited about getting a break at learning the business. Back then, animation fandom wasn’t as developed as it has become since, so I didn’t know that Johnny Gent was the best Popeye artist and could animate a punch better than anyone in the business.

I knew about Bill Tytla and Freddy Moore, having studied their work on old super-8 millimeter sound versions of sequences from Disney cartoons released for home viewing during the late 1960s-early 1970s. But the plain fact of the matter was that I’d been more of a comic book fan and could pick out a comic book artist’s style just by glancing at the line work on the printed page. So I was shocked and surprised to see the name “Boring” on the folder of one of the first TUBBY THE TUBA scenes I was given to inbetween.

The name wasn’t written in the animator’s area of the folder, but rather in the layout section. I looked at the layout drawings in the folder and recognized the familiar sketchy line that I’d seen inked by brush in my favorite Superman comic books of the 1950s. Could this be the same Wayne Boring, whose images of Superman I strained to copy back when I could barely control my pencil? If so, what the heck was he doing in this out-of-the-way place on Long Island and why had he stopped drawing Superman? These were the questions of a person who had no idea of the realities of life as an animation or comic artist. But I didn’t ask --- again, I was too excited at not only getting the chance to draw and learn the animation business, but also getting paid to do it. The other reason was that in those days older artists were looked upon with respect, and I didn’t think it my place to question his choice of jobs. On the other hand, why wouldn’t Wayne Boring work on TUBBY, after all it was turning out to be the single biggest source of employment for the New York animation industry, both union and non-union talent. (A side note: the union strike at NYIT gave me my second real break --- but that’s a story for another time.)

Anyway, I asked the head assistant animator to point out Wayne Boring. I took it from there, politely introducing myself as a long-time fan. I didn’t know it, but Wayne was already past retirement age --- a youthful-looking 70 years old. He was short in height and had a certain military air about him, walking with a slight rolling gate that reminded me of sailors on shore leave. I found out during our few conversations that I was right, he’d been in the Navy and referred to himself as being a Chief Petty Officer.

In that introductory meeting of ours, I brought along two pages I’d chosen from all the hundreds of Superman drawings in Wayne’s style I’d copied from comic books when I was 11 or 12 years old. I just wanted him to know that he’d had a dramatic influence on my life.

“Yep, Johnny Boy,” Wayne said, “I recognize my poses.”

From that point on, Wayne always addressed me as “Johnny” or “Johnny Boy” when we’d pass each other in the hallway or outside the studio building. He was the silent type who kept to himself, going out alone for lunch and staying at his desk, working on layout drawings.

I didn’t pester Wayne about his days drawing Superman --- I picked up a strong impression that he didn’t want to talk about it. I figured after a little while of getting to know him, I might find the opportunity to broach that subject. I never had that chance.

Four weeks after I met Wayne Boring at NYIT, he left. I knew nothing about his impending departure until that final Friday afternoon, when I heard about it in conversation with several other artists. I immediately went to Wayne’s office, which he shared with storyboard artist George Singer, to say goodbye.

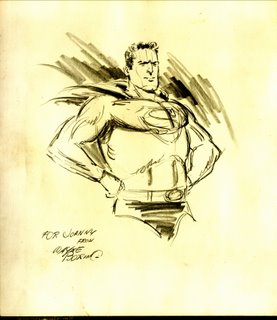

Wayne was alone and he and I shook hands, exchanging good wishes. Then just as I was about to leave to return to my desk, Wayne slide a drawing out from under his desk blotter and presented it to me. “For you, Johnny.”

It was a pencil sketch on Bristol board of Superman in his classic heroic fists-on-hips pose.

Wayne said, “Don’t tell anyone I did this for you. You never bothered me for a drawing, like all the rest here have.”

That Superman sketch is still one of my most prized possessions.

(Click on the image for a larger view.)

JOHN’S BLOG MEMORIES OF NYIT: PART 2

Growing up in Brooklyn during the 1950s, my childhood was full of day-and-night dreams of being powerful like Popeye, Mighty Mouse, and Superman. Oh, what I wouldn’t have given to be able to fly through the air, leap over buildings in a single bound, or be able to pound the neighborhood bully by simple swallowing a mouthful of spinach.

These fantasies were fueled by images I’d seen in the old Terrytoons and Fleischer/Paramount cartoons broadcasted over the local TV airwaves. From the ages of 5 through 12, I was glued to the screen of my family’s old black and white Sylvania, soaking it all in. And when I wasn’t watching Popeye, Mighty Mouse, or Superman cartoons, I was reading their comic books and copying their images onto whatever paper I could find, using whatever pencils I could get from my father, who was a mechanical draftsman.

It was at NYIT that I met some of the artists who created those images of power---power I so desperately wanted to have coursing through my tiny, childhood muscles.

When I first started working at NYIT, I expected to meet animators, but I didn’t realize they were responsible for some of my most cherished childhood fantasies. I was just excited about getting a break at learning the business. Back then, animation fandom wasn’t as developed as it has become since, so I didn’t know that Johnny Gent was the best Popeye artist and could animate a punch better than anyone in the business.

I knew about Bill Tytla and Freddy Moore, having studied their work on old super-8 millimeter sound versions of sequences from Disney cartoons released for home viewing during the late 1960s-early 1970s. But the plain fact of the matter was that I’d been more of a comic book fan and could pick out a comic book artist’s style just by glancing at the line work on the printed page. So I was shocked and surprised to see the name “Boring” on the folder of one of the first TUBBY THE TUBA scenes I was given to inbetween.

The name wasn’t written in the animator’s area of the folder, but rather in the layout section. I looked at the layout drawings in the folder and recognized the familiar sketchy line that I’d seen inked by brush in my favorite Superman comic books of the 1950s. Could this be the same Wayne Boring, whose images of Superman I strained to copy back when I could barely control my pencil? If so, what the heck was he doing in this out-of-the-way place on Long Island and why had he stopped drawing Superman? These were the questions of a person who had no idea of the realities of life as an animation or comic artist. But I didn’t ask --- again, I was too excited at not only getting the chance to draw and learn the animation business, but also getting paid to do it. The other reason was that in those days older artists were looked upon with respect, and I didn’t think it my place to question his choice of jobs. On the other hand, why wouldn’t Wayne Boring work on TUBBY, after all it was turning out to be the single biggest source of employment for the New York animation industry, both union and non-union talent. (A side note: the union strike at NYIT gave me my second real break --- but that’s a story for another time.)

Anyway, I asked the head assistant animator to point out Wayne Boring. I took it from there, politely introducing myself as a long-time fan. I didn’t know it, but Wayne was already past retirement age --- a youthful-looking 70 years old. He was short in height and had a certain military air about him, walking with a slight rolling gate that reminded me of sailors on shore leave. I found out during our few conversations that I was right, he’d been in the Navy and referred to himself as being a Chief Petty Officer.

In that introductory meeting of ours, I brought along two pages I’d chosen from all the hundreds of Superman drawings in Wayne’s style I’d copied from comic books when I was 11 or 12 years old. I just wanted him to know that he’d had a dramatic influence on my life.

“Yep, Johnny Boy,” Wayne said, “I recognize my poses.”

From that point on, Wayne always addressed me as “Johnny” or “Johnny Boy” when we’d pass each other in the hallway or outside the studio building. He was the silent type who kept to himself, going out alone for lunch and staying at his desk, working on layout drawings.

I didn’t pester Wayne about his days drawing Superman --- I picked up a strong impression that he didn’t want to talk about it. I figured after a little while of getting to know him, I might find the opportunity to broach that subject. I never had that chance.

Four weeks after I met Wayne Boring at NYIT, he left. I knew nothing about his impending departure until that final Friday afternoon, when I heard about it in conversation with several other artists. I immediately went to Wayne’s office, which he shared with storyboard artist George Singer, to say goodbye.

Wayne was alone and he and I shook hands, exchanging good wishes. Then just as I was about to leave to return to my desk, Wayne slide a drawing out from under his desk blotter and presented it to me. “For you, Johnny.”

It was a pencil sketch on Bristol board of Superman in his classic heroic fists-on-hips pose.

Wayne said, “Don’t tell anyone I did this for you. You never bothered me for a drawing, like all the rest here have.”

That Superman sketch is still one of my most prized possessions.

Friday, May 26, 2006

The Nature of Talent

I'm sure we've all looked at other people's work with envy and wished we were as good. We'd all like to be better than we are. What's stopping us? Is it a lack of talent?

There was an interesting article in the New York Times Magazine on May 7, 2006 called "A Star Is Made: Where does talent really come from?" by Stephen J. Dubner and Steven D. Levitt. Here are a few quotes from the article.

"Anders Ericsson, a 58-year-old psychology professsor at Florida State University...is the ringleader of what might be called the Expert Performance Movement, a loose coalition of scholars trying to answer an important and seemingly primordial question: When someone is very good at a given thing, what is it that actually makes him good?"

"Their work, compiled in the "Cambridge Handbook of Expertise and Expert Performance," a 900-page academic book that will be published next month, makes a rather startling assertion: the trait we commonly call talent is highly overrated. Or, put another way, expert performers -- whether in memory or surgery, ballet or computer programming -- are nearly always made, not born. And yes, practice does make perfect. These may be the sort of cliches that parents are fond of whispering to their children. But these particular cliches just happen to be true.

"Ericsson's research suggests a third cliche as well: when it comes to choosing a life path, you should do what you love -- because if you don't love it, you are unlikely to work hard enough to get very good. Most people naturally don't like to do things they aren't "good" at. So they often give up, telling themselves they simply don't possess the talent for math or skiing or the violin. But what they really lack is the desire to be good and to undertake the deliberate practice that would make them better.

""I think the most general claim here," Ericsson says of his work, "is that a lot of people believe there are inherent limits they were born with. But there is surprisingly little hard evidence that anyone could attain any kind of exceptional performance without spending a lot of time perfecting it." This is not to say that all people have equal potential. Michael Jordan, even if he hadn't spent countless hours in the gym, would still have been a better basketball player than most of us. But without those hours in the gym, he would never have become the player he was."

There was an interesting article in the New York Times Magazine on May 7, 2006 called "A Star Is Made: Where does talent really come from?" by Stephen J. Dubner and Steven D. Levitt. Here are a few quotes from the article.

"Anders Ericsson, a 58-year-old psychology professsor at Florida State University...is the ringleader of what might be called the Expert Performance Movement, a loose coalition of scholars trying to answer an important and seemingly primordial question: When someone is very good at a given thing, what is it that actually makes him good?"

"Their work, compiled in the "Cambridge Handbook of Expertise and Expert Performance," a 900-page academic book that will be published next month, makes a rather startling assertion: the trait we commonly call talent is highly overrated. Or, put another way, expert performers -- whether in memory or surgery, ballet or computer programming -- are nearly always made, not born. And yes, practice does make perfect. These may be the sort of cliches that parents are fond of whispering to their children. But these particular cliches just happen to be true.

"Ericsson's research suggests a third cliche as well: when it comes to choosing a life path, you should do what you love -- because if you don't love it, you are unlikely to work hard enough to get very good. Most people naturally don't like to do things they aren't "good" at. So they often give up, telling themselves they simply don't possess the talent for math or skiing or the violin. But what they really lack is the desire to be good and to undertake the deliberate practice that would make them better.

""I think the most general claim here," Ericsson says of his work, "is that a lot of people believe there are inherent limits they were born with. But there is surprisingly little hard evidence that anyone could attain any kind of exceptional performance without spending a lot of time perfecting it." This is not to say that all people have equal potential. Michael Jordan, even if he hadn't spent countless hours in the gym, would still have been a better basketball player than most of us. But without those hours in the gym, he would never have become the player he was."

A. Film L.A.

Hans Perk continues to post amazing historical material on his blog. He's put up the animator draft for the Mickey Mouse cartoon The Pointer and an article by Disney composer Albert Malotte on "The Relation of Music to Animation." I've added a link to A. Film L.A. on my sidebar and I'll be checking it regularly to see what new treasures Hans posts.

Thursday, May 25, 2006

Get Out of the Kitchen

Yesterday, I made a comparison between broadcasters and the customers in a restaurant. However, the analogy is flawed. Customers in restaurants are ordering food for themselves, but movie studios and broadcasters are not the end users. They are buying to resell to millions of customers. As a result, they are not ordering based on their own tastes, but what they believe other people will want.

The problem is that they really have no clue. If you go to the movies or watch television you know this intuitively, but a new book by Bill Carter called Desperate Networks provides hard evidence that the highly paid executives in TV are no better at picking hits than anyone who can toss a coin.

You want proof? All the U.S. networks turned down American Idol. It got on Fox because Rupert Murdoch's daughter saw the British version of the show and advised her father to buy it. This was after Fox had turned it down.

ABC rejected Survivor and CSI. NBC turned down Desperate Housewives. Fox turned down Friends. CBS turned down Survivor and only relented when the producers were able to find enough sponsors to finance the show. Of course, we'll never know how many hit shows never made it to air because everyone rejected them.

Failures like Fired Up, Built to Last, Men Behaving Badly, Jenny, Conrad Bloom, The Apprentice with Martha Stewart, Mr. Personality, Coupling, Whoopi, Boomtown, Father of the Pride, and The Rebel Billionaire were put on the air. In fact, the majority of new series don't make it to a second season and the majority of feature films lose money, which is why I say that choosing projects by tossing a coin would produce better results. Over the long term, you'd have a 50% success rate.

So what does this mean for creative people? It means that there's no relationship between your project's value and how it is judged by media companies. Only the audience can decide. Therefore, the best approach is figuring out how to bypass the media companies and go directly to the audience.

Doing it with the web or self-publishing is easy. The hard part is supporting yourself while you develop a point of view and a body of work. However, nobody can mess with your work (and it's a guarantee that media companies will mess with it), and if you can build an audience large enough to support yourself, you're free to do the work you want to do. Bill Plympton, JibJab and Michel Gagne are doing it and should serve as an inspiration to us all.

The restaurant analogy devalues what we do. As cooks, we're just there to take orders from people with questionable taste. I think it's time to get out of the kitchen.

The problem is that they really have no clue. If you go to the movies or watch television you know this intuitively, but a new book by Bill Carter called Desperate Networks provides hard evidence that the highly paid executives in TV are no better at picking hits than anyone who can toss a coin.

You want proof? All the U.S. networks turned down American Idol. It got on Fox because Rupert Murdoch's daughter saw the British version of the show and advised her father to buy it. This was after Fox had turned it down.

ABC rejected Survivor and CSI. NBC turned down Desperate Housewives. Fox turned down Friends. CBS turned down Survivor and only relented when the producers were able to find enough sponsors to finance the show. Of course, we'll never know how many hit shows never made it to air because everyone rejected them.

Failures like Fired Up, Built to Last, Men Behaving Badly, Jenny, Conrad Bloom, The Apprentice with Martha Stewart, Mr. Personality, Coupling, Whoopi, Boomtown, Father of the Pride, and The Rebel Billionaire were put on the air. In fact, the majority of new series don't make it to a second season and the majority of feature films lose money, which is why I say that choosing projects by tossing a coin would produce better results. Over the long term, you'd have a 50% success rate.

So what does this mean for creative people? It means that there's no relationship between your project's value and how it is judged by media companies. Only the audience can decide. Therefore, the best approach is figuring out how to bypass the media companies and go directly to the audience.

Doing it with the web or self-publishing is easy. The hard part is supporting yourself while you develop a point of view and a body of work. However, nobody can mess with your work (and it's a guarantee that media companies will mess with it), and if you can build an audience large enough to support yourself, you're free to do the work you want to do. Bill Plympton, JibJab and Michel Gagne are doing it and should serve as an inspiration to us all.

The restaurant analogy devalues what we do. As cooks, we're just there to take orders from people with questionable taste. I think it's time to get out of the kitchen.

Old and New

Wednesday, May 24, 2006

Customers, Waiters and Cooks

I suspect we've all eaten in restaurants. The waiter hands us a menu and mentions the specials. We order what we want, sometimes asking for a varation that leaves out the onions or replaces the french fries with a salad. The waiter just writes down what we want and the food is brought to our table.

We get the meal that we want. The waiter is happy to bring us anything, as our business keeps the doors open and generates tips. But what about the cook?

The cook has worked hard to create the day's special. He has honed his craft for years in order to create meals that are memorable, yet nobody is ordering the special. The cook tells the waiter to push it harder, but the waiter responds that he doesn't want to alienate the customers. The cook is frustrated. He's not allowed to reach his potential and show what he can do. Instead, he's stuck endlessly frying hamburgers.

I doubt that any of us has ever looked at a menu and asked ourselves what we could order that the cook would enjoy making. We don't go to restaurants to satisfy the cook; we go to satisfy ourselves.

Why am I telling you this? It's because I believe that this is analagous to how the film and TV industries work. The customers are the movie studios or the broadcasters. The waiters are producers and the creative people are the cooks.

For years, I worked in animation studios and never understood the requests that came in the door. From my perspective, the designs were problematic and the stories made little sense. That was my motivation to create a show, figuring that if I created it, I could shape it as I saw fit. I was wrong.

I sat in a meeting with our broadcasters and producers where the broadcaster-customer asked us to "hold the onions." The producer-waiter immediately said yes. I, as the cook-creator, was dumbfounded. The show was significantly different without the onions, but it wasn't even up for discussion. The decision was made and I had to live with it.

I considered the work I created to be a finished product, done as perfectly as I was able. The broadcaster-customer didn't see it as finished at all; it was simply a menu option. The producer-waiter was happy to serve anything that would be paid for.

That's a dynamic that I didn't understand until I experienced it. The restaurant analogy works because we've all been customers. If the waiter forced us to order something or prevented us from substituting, we'd probably avoid that restaurant in the future. And if the cook ever came out of the kitchen to criticize our choices, we'd think he was crazy.

Inside our studios, where we're trying to cook up memorable films, we often think everybody outside is crazy. They're not, but they're operating with the same expectations we have when we go to a restaurant. Our industry is structured in such a way that we're stuck frying hamburgers.

The above analogy isn't perfect; there's a very big flaw in it that I'll discuss tomorrow. A new book about the TV business called Desperate Networks shows why the restaurant analogy doesn't work and why we should think about getting out of the restaurant business.

We get the meal that we want. The waiter is happy to bring us anything, as our business keeps the doors open and generates tips. But what about the cook?

The cook has worked hard to create the day's special. He has honed his craft for years in order to create meals that are memorable, yet nobody is ordering the special. The cook tells the waiter to push it harder, but the waiter responds that he doesn't want to alienate the customers. The cook is frustrated. He's not allowed to reach his potential and show what he can do. Instead, he's stuck endlessly frying hamburgers.

I doubt that any of us has ever looked at a menu and asked ourselves what we could order that the cook would enjoy making. We don't go to restaurants to satisfy the cook; we go to satisfy ourselves.

Why am I telling you this? It's because I believe that this is analagous to how the film and TV industries work. The customers are the movie studios or the broadcasters. The waiters are producers and the creative people are the cooks.

For years, I worked in animation studios and never understood the requests that came in the door. From my perspective, the designs were problematic and the stories made little sense. That was my motivation to create a show, figuring that if I created it, I could shape it as I saw fit. I was wrong.

I sat in a meeting with our broadcasters and producers where the broadcaster-customer asked us to "hold the onions." The producer-waiter immediately said yes. I, as the cook-creator, was dumbfounded. The show was significantly different without the onions, but it wasn't even up for discussion. The decision was made and I had to live with it.

I considered the work I created to be a finished product, done as perfectly as I was able. The broadcaster-customer didn't see it as finished at all; it was simply a menu option. The producer-waiter was happy to serve anything that would be paid for.

That's a dynamic that I didn't understand until I experienced it. The restaurant analogy works because we've all been customers. If the waiter forced us to order something or prevented us from substituting, we'd probably avoid that restaurant in the future. And if the cook ever came out of the kitchen to criticize our choices, we'd think he was crazy.

Inside our studios, where we're trying to cook up memorable films, we often think everybody outside is crazy. They're not, but they're operating with the same expectations we have when we go to a restaurant. Our industry is structured in such a way that we're stuck frying hamburgers.

The above analogy isn't perfect; there's a very big flaw in it that I'll discuss tomorrow. A new book about the TV business called Desperate Networks shows why the restaurant analogy doesn't work and why we should think about getting out of the restaurant business.

Following Up

Yesterday I mentioned that Hans Perk started a blog where he posted animator identifications for Mr. Duck Steps Out. He's answered my questions about the animators and has now posted the animator draft for Thru the Mirror, one of the most delightful Mickey Mouse cartoons of the 1930's. That's worth checking out. Eventually, I'll create mosaics for those two cartoons.

Hans doesn't have the draft for the Donald Duck cartoon Duck Pimples. That contains some great work by Milt Kahl and John Sibley. In particular, there's some beautiful animation on the woman character and I'd love to know who did it. Does anybody have the draft or can they identify the animator of the woman?

I also pointed out some animation samples at Spline Doctors yesterday. Tim Linklater has put together a page of links to demo reels, including animators who worked at Pixar and Blue Sky. There's more on this page than you can watch in a day, so it's worth bookmarking to explore over time.

Those of you who were intrigued by the Jim Tyer stills I mentioned yesterday might want to see some Tyer animation in motion. Thad K has posted Cheese Burglars, which contains animation by Tyer, Ben Solomon and William Henning, identifications courtesy of Milton Knight. And if you clink on this link to YouTube.com, you can have yourself a mini-festival of Jim Tyer's animation.

Hans doesn't have the draft for the Donald Duck cartoon Duck Pimples. That contains some great work by Milt Kahl and John Sibley. In particular, there's some beautiful animation on the woman character and I'd love to know who did it. Does anybody have the draft or can they identify the animator of the woman?

I also pointed out some animation samples at Spline Doctors yesterday. Tim Linklater has put together a page of links to demo reels, including animators who worked at Pixar and Blue Sky. There's more on this page than you can watch in a day, so it's worth bookmarking to explore over time.

Those of you who were intrigued by the Jim Tyer stills I mentioned yesterday might want to see some Tyer animation in motion. Thad K has posted Cheese Burglars, which contains animation by Tyer, Ben Solomon and William Henning, identifications courtesy of Milton Knight. And if you clink on this link to YouTube.com, you can have yourself a mini-festival of Jim Tyer's animation.

Tuesday, May 23, 2006

Odds and Ends

Reader comments are still coming in on earlier entries, so if there's an entry you're interested in, check back to see if there's anything new there. In particular, I want to point to Hans Perk's comment on the Anna and Bella entry, as he worked on the film and shares some memories of its production. Hans has also started a blog, which includes the animator draft for Mr. Duck Steps Out, one of the nicer Jack King Donald Duck cartoons. It turns out that the cartoon features animation by Ken Muse and Dick Lundy. I've posted a comment there asking about who some of the other animators are. Many of the names are unknown to me. I hope that Hans can answer my questions.

Speaking of animator drafts, Jenny Lerew has started posting the drafts from "All the Cats Join In," a great sequence from Make Mine Music that was directed by Jack Kinney. Get the rest of them posted, Jenny! Make Mine Music and Melody Time contain some great work and deserve more attention. If you haven't seen "All the Cats," then you can watch it here courtesy of YouTube.com.

The Inspiration Grab-Bag has a lot of stills of Jim Tyer's animation. We're all familiar with stretch and squash, but Tyer distorted his characters in very unexpected directions. I wrote about Tyer here. That article was printed in a different form in Animation Blast #6, which is sold out. Hey Amid! Any plans to bring older issues of the Blast back into print somehow?

And for you students out there, the Spline Doctors are posting work by their students. If your goal is to animate professionally, these folks are your competition. In any case, there's some nice work there that's worth watching.

Speaking of animator drafts, Jenny Lerew has started posting the drafts from "All the Cats Join In," a great sequence from Make Mine Music that was directed by Jack Kinney. Get the rest of them posted, Jenny! Make Mine Music and Melody Time contain some great work and deserve more attention. If you haven't seen "All the Cats," then you can watch it here courtesy of YouTube.com.

The Inspiration Grab-Bag has a lot of stills of Jim Tyer's animation. We're all familiar with stretch and squash, but Tyer distorted his characters in very unexpected directions. I wrote about Tyer here. That article was printed in a different form in Animation Blast #6, which is sold out. Hey Amid! Any plans to bring older issues of the Blast back into print somehow?

And for you students out there, the Spline Doctors are posting work by their students. If your goal is to animate professionally, these folks are your competition. In any case, there's some nice work there that's worth watching.

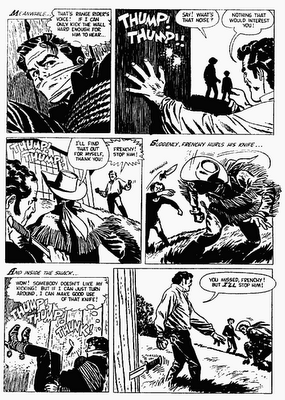

Friday, May 19, 2006

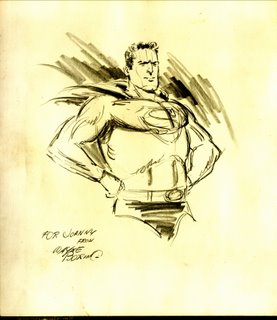

Popeye

I know I said no more entries until Tuesday, but I wanted to point out a nice piece on the Popeye cartoons, focusing especially on the two reel specials, over at Greenbriar Picture Shows. There's lots of interesting artwork there that was done to encourage theaters to book Popeye cartoons, including the piece at left.

I know I said no more entries until Tuesday, but I wanted to point out a nice piece on the Popeye cartoons, focusing especially on the two reel specials, over at Greenbriar Picture Shows. There's lots of interesting artwork there that was done to encourage theaters to book Popeye cartoons, including the piece at left.See you Tuesday.

Thursday, May 18, 2006

No Updates Until Tuesday

I'm stepping away from the keyboard for a while, so there won't be any updates until Tuesday. See you then.

A Letter from Dick Lundy

I wrote a history of MGM cartoons for issue 18 of the film journal The Velvet Light Trap, which appeared in 1978. I don't recommend searching out the article, as it has been done better by many others since then. However, in researching the article, I contacted several former MGM animation staffers who were kind enough to answer my questions.

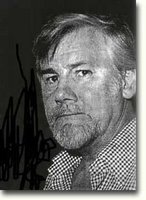

I wrote a history of MGM cartoons for issue 18 of the film journal The Velvet Light Trap, which appeared in 1978. I don't recommend searching out the article, as it has been done better by many others since then. However, in researching the article, I contacted several former MGM animation staffers who were kind enough to answer my questions.One who replied in depth was Dick Lundy (1907-1990). The picture of him here is from his time at Hanna Barbera. What's below is his letter in full, which is a summary of his entire career. Anything in square brackets is an annotation by me, the rest is Lundy.

Feb. 6, 1976

Dear Mark,

Thank you for your interest in me and my history. You must have gotten some wrong information on the Woodland Cafe direction. If this was a Disney picture, I probably animated on it and it was probably directed by Jaxon. I have no record of directing a picture by that name. [Lundy is correct. The cartoon was directed by Wilfred Jackson and Lundy animated the Apache dance in it.] It is true I started at Disney in July 1929. I started in the ink and paint dept. Six weeks or 2 months later I was put in as in inbetweener or assistant animator (at that time they were both the same thing). In March 1930 I was promoted to animator. I established the dance in the 3 Pigs going around in a circle singing "Who's afraid." This same routine was used in the other pig pictures which followed. I also established the antics of the Duck in Orphans Benefit [1934]. I animated the duck thru out this picture. They changed the model of Donald and made him more cute. I also animated on Snow White.

In 1937 they made me a director. Here is a list of the duck pictures I directed at Disney: Sea Scouts, [The] Riveter, Good Time for a Dime, Don[ald]'s Camera, Village Smithy, Don[ald's] Garden, Fly[ing] Jalopy, and [Donald's] Tire Trouble. I also directed about 10,500 feet of Navy training pictures. I left Disney's in Oct. 1943.

I started at Walter Lantz in Nov. 1943 as an animator. I animated 6 months and started in direction. Maybe you don't want a list of pictures I directed at Lantz, but if you do here is the list. These were Wooody Woodpecker, Andy Panda and some of Lantz's Silly Symphonies [the Lantz music series were Swing Symphonies and Musical Miniatures]. Sliphorn King of Polaroo, Crow Crazy, Enemy Bacteria (1300 ft 1/2 live for Navy), Poet and Peasant, Apple Andy, Bathing Buddies, Ready [should be Reddy] Kilowatt (a commercial) 1070 ft, Wacky Weed, Smoked Hams, Coo Coo Bird, [Musical Moments from] Chopin, [Overture to] Wm. Tell, Well Oiled, Solid Ivory, Circus Symphony [released as The Band Master], Top Hat [released as The Mad Hatter], Woody and the Beanstalk [released as Woody the Giant Killer], The Story of Human Energy (880 ft commercial), The Egg and I (commercial for live action picture), Banquet Busters, Kiddie Concert, Pixie Picnic, [illegible](344 ft commercial), Wacky Bye Baby, Playful Pelican, Dog Tax Dodgers, Wet Blanket Policy, Wild and Woody, Scrappy Birthday, Droolers Delight, Puny Express [credited to Walter Lantz as director], 12 two minute Coca Cola commercials. I also timed out 3 more pictures when the studio closed down at the end of 1948.

I worked for Raphael S. Wolff Productions as supervisor and director 4-'49 to 5-'50. There I received an award from N.Y. for a Kelvinator 1 minute commercial.

I started at MGM on 5-15-1950. I directed there for one year and a half, leaving there at the end of October 1951. The following titles are the pictures I directed. Caballero Droopy (This is the only picture that wasn't a Barney Bear. Droopy the dog was a Tex Averty creation.), The Little Wise Cracker [released as Little Wise Quacker], Cobs and Robbers, Heir Bear, Busy Body Bear, Barney's Hungry Cousin, Wee Willie Wildcat, Half-Pint Palamino, Impossible Possum, Sleepy-time Squirrel, Bird-Brain Bird Dog.

From MGM I went to Dudleys production managing and directing. Then I freelanced animation for about 9 months and in 1959 (March) I started at Hanna-Barbera animating. I retired the end of 1973 and have been working everyone [everywhere?] I can since. Now to answer some of your questions.

I started at MGM 5-15-1950. Tex Avery and Quimby had a little squabble and Tex left. According to Quimby, Tex would not return. I also knew that Quimby had wanted to start a third unit for a long time. So I thot that even if Tex did come back, Quimby would have his 3rd unit. It didn't turn out that way.

I was working at R.S. Wolff Productions and Quimby called me and offered me more money and a better deal than I had or hope to have had.

I already listed the titles I directed. (I went to MGM as a director.) The first one I directed was a Droopy Dog which was created by Tex Avery (I believe).

Barney Bear was already established when I got there, both drawing and personality wise. I thot the Wally Beery type character was a loveable and sympathetic personality, so I went on from there. I stepped into Avery's unit with the same animators - Walt Clinton, Mike Lah, Grant Simmons with Bob Bentley as a new animator. I also used Ray Patterson from the Cat and Mouse unit every other picture. It was a pretty good crew.

The story men were there also. Heck Allen and Jack Cosgriff. Quimby had a layout man that he thot had a good reputation - Art Heinemann, who I had worked with before at Lantz's, so I said that was okay by me. After about 3 pictures he crossed Quimby in the wrong way and was let go. Then I had Quimby hire Hal Doughty (I think that his how you spell it).

I auditioned for a voice and finally settled for Paul ----I can't remember his last name. [Lundy is probably referring to Paul Frees, who supplied the voice of Barney Bear.] He was very good. He is doing voices for Hanna-Barbera off and on now. As I remember the budget, I think it was around half way between Lantz and Disney, about $30,000?

When I was animating at Disney's I was considered a personality animator. I always tried to give the personality a comedy twist, with a gesture, a body action or a twist of the mouth or head. When I animated dances I tried to put in the same thing. Now with a funny personality leading up to a physical gag which was funny (usually the way a character reacted) you usually ended up with something twice as funny. Tex's pictures were mostly gag type pictures with a good timing, with a little personality thrown in. The Cat and Mice had personality with slapstick gags. Both of these series were set at a very fast pace. I wanted Barney to have a slower pace and likeable appeal to the audiences. Disney has this type of action in the Silly Symphonies. That is what I was striving for in Barney. Sometimes I achieved this and sometimes I failed.

If you look at the history of animation, you will notice as the animated cartoon got into a slump, there was always something that was developed that made cartoons raise up and become in style again. Around 1928-29 the cartoons were in a slump and sound and Disney came along and revived it again. In the 1940's television came along and revived it again. In the late '50's Hanna Barbera revived it with limited animation. Animation had reached a cost per foot which wasn't commercial. The limited animation was the answer. Now it is in the decline and something or someone will bring out something which will bring cartoons into their own again.

I have never had a desire to direct a feature. I guess I never even thot of it. The cost is great even in shorts and a feature would really be up into dough. Nobody ever offered to put up that kind of money - to me at least.

I hope this helps you out and answers some of your questions. I am retired now. I spent 44 years in the industry and am now satisfied to let the younger people take over. I've had my fun, let them enjoy it.

Sincerely,

Dick Lundy

Wednesday, May 17, 2006

The Future of Hollywood

This Fortune article, "The Future of Hollywood" by Marc Gunther, is worth reading. As Peter Chernin, CEO of Fox says, "I don't think it's an overstatement to say that it's been the most revolutionary period in the history of mass media."

The changes that swept through the animation business in the '90's had to do with how animation was created. There was a shift to computer hardware and software. The changes happening now are all about how content is delivered. Instead of movies and TV shows appearing at specific times and places, content is now available on demand and viewable anywhere thanks to cell phones, iPods and computers.

If you're of an entrepreneurial bent, it's important to keep up with these emerging markets. There are new places to sell animation and the good news is that these places are interested in short films. If you're an employee, it still pays to know what's happening. When markets shift, some companies win and other lose. If you see the shift coming, you've got time to make sure that you're working for a winner.

The changes that swept through the animation business in the '90's had to do with how animation was created. There was a shift to computer hardware and software. The changes happening now are all about how content is delivered. Instead of movies and TV shows appearing at specific times and places, content is now available on demand and viewable anywhere thanks to cell phones, iPods and computers.

If you're of an entrepreneurial bent, it's important to keep up with these emerging markets. There are new places to sell animation and the good news is that these places are interested in short films. If you're an employee, it still pays to know what's happening. When markets shift, some companies win and other lose. If you see the shift coming, you've got time to make sure that you're working for a winner.

Tuesday, May 16, 2006

IDT and Me

"We consider ourselves like a Pixar on steroids." - Morris Berger, CEO of IDT Entertainment, July 22, 2003.

Liberty Media to Buy IDT Entertainment - Associated Press.

There's something about the animation business that attracts certain types of business people. Many are egotistic enough to see themselves as the next Walt Disney. Others just see the profits and figure they're smart enough to get their share.

The problem is that these people know absolutely nothing about the animation business. They don't understand the film or television markets and they know less than nothing about how to organize a studio to produce a cartoon. Some of these people start up companies on a small scale, but occasionally you get somebody with real money. Those are the people who fail big and do the most damage.

I wouldn't be writing about IDT except that I had a personal experience with them early on in their quest to become players in animation. We were trying to complete the financing to make another 26 half hours of the cgi show I created called Monster By Mistake. IDT was a telecom company looking to buy their way into the animation business. They had deep pockets, but they didn't just want to invest; they wanted their studios to do work on the show.

In co-productions, the partners divvy up the work based on the size of their investment. IDT was to build whatever new characters and sets we needed and then light the 26 half hours. Their character models were unusable; I spent weeks trying to patch some of them up.

After dithering for months on lighting issues, IDT bailed out on us. They never lit a single episode. We had to locate a subcontractor to take on the work and the show delivered five months late as a result. If you've ever worked in TV, you know that the cardinal sin is delivering late.

In addition to ruining Monster By Mistake, they went on a buying spree. They bought into Mainframe in Vancouver. They bought into Vanguard. They became minority investors in Archie Comics. They bought Anchor Bay, a home video distributor. They bought Dan Krech Productions and fired the management. They bought Film Roman, but the artists were no fools. Seeing how freely IDT was spending money, they voted to unionize, which is perhaps the only good thing that ever came out of IDT.

They managed to subcontract the feature Happily N'ever After when the producers decided to ditch their pencil animation crew (which included Disney veterans) and go the 3D route. Several months later, IDT no longer had the project and it was subcontracted to several other studios. I'm guessing that they once again failed to deliver.

Recently, they created a new studio in Vancouver to do Space Chimps, even though they already own Mainframe there and even though their Toronto studio just finished Everybody's Hero. Why build a new studio when you already own a local studio that could do the work? Why build a studio when you already have an experienced feature crew ready to start another picture?

Now they've sold IDT Entertainment to Liberty Media for $186 million and Liberty Media assumes an undisclosed amount of IDT's debt. So much for "Pixar on steroids." When I read that quote, I immediately said that IDT was closer to Filmation on laxatives. IDT is, by far, the worst company I have ever seen in my 29 years in the business. While I couldn't go public while I was working with them for obvious reasons, I sent emails to everyone I knew in the business warning them to avoid IDT.

You have to believe that they lost a lot of money or why would they bother to sell? You also have to believe that they have no faith in Everybody's Hero. If they believed it was going to be a hit, they could have taken the profits before selling or used it to raise the company's price.

I know people who work at several IDT facilities and I wish them the best of luck with their new owners. But so far as IDT is concerned, good riddance to bad rubbish.

Liberty Media to Buy IDT Entertainment - Associated Press.

There's something about the animation business that attracts certain types of business people. Many are egotistic enough to see themselves as the next Walt Disney. Others just see the profits and figure they're smart enough to get their share.

The problem is that these people know absolutely nothing about the animation business. They don't understand the film or television markets and they know less than nothing about how to organize a studio to produce a cartoon. Some of these people start up companies on a small scale, but occasionally you get somebody with real money. Those are the people who fail big and do the most damage.

I wouldn't be writing about IDT except that I had a personal experience with them early on in their quest to become players in animation. We were trying to complete the financing to make another 26 half hours of the cgi show I created called Monster By Mistake. IDT was a telecom company looking to buy their way into the animation business. They had deep pockets, but they didn't just want to invest; they wanted their studios to do work on the show.

In co-productions, the partners divvy up the work based on the size of their investment. IDT was to build whatever new characters and sets we needed and then light the 26 half hours. Their character models were unusable; I spent weeks trying to patch some of them up.

After dithering for months on lighting issues, IDT bailed out on us. They never lit a single episode. We had to locate a subcontractor to take on the work and the show delivered five months late as a result. If you've ever worked in TV, you know that the cardinal sin is delivering late.

In addition to ruining Monster By Mistake, they went on a buying spree. They bought into Mainframe in Vancouver. They bought into Vanguard. They became minority investors in Archie Comics. They bought Anchor Bay, a home video distributor. They bought Dan Krech Productions and fired the management. They bought Film Roman, but the artists were no fools. Seeing how freely IDT was spending money, they voted to unionize, which is perhaps the only good thing that ever came out of IDT.

They managed to subcontract the feature Happily N'ever After when the producers decided to ditch their pencil animation crew (which included Disney veterans) and go the 3D route. Several months later, IDT no longer had the project and it was subcontracted to several other studios. I'm guessing that they once again failed to deliver.

Recently, they created a new studio in Vancouver to do Space Chimps, even though they already own Mainframe there and even though their Toronto studio just finished Everybody's Hero. Why build a new studio when you already own a local studio that could do the work? Why build a studio when you already have an experienced feature crew ready to start another picture?

Now they've sold IDT Entertainment to Liberty Media for $186 million and Liberty Media assumes an undisclosed amount of IDT's debt. So much for "Pixar on steroids." When I read that quote, I immediately said that IDT was closer to Filmation on laxatives. IDT is, by far, the worst company I have ever seen in my 29 years in the business. While I couldn't go public while I was working with them for obvious reasons, I sent emails to everyone I knew in the business warning them to avoid IDT.

You have to believe that they lost a lot of money or why would they bother to sell? You also have to believe that they have no faith in Everybody's Hero. If they believed it was going to be a hit, they could have taken the profits before selling or used it to raise the company's price.

I know people who work at several IDT facilities and I wish them the best of luck with their new owners. But so far as IDT is concerned, good riddance to bad rubbish.

Monday, May 15, 2006

Anna and Bella

If you haven't seen this film by Borge Ring, please watch it before you read what's below. I'd hate to spoil it for anybody.

This is one of my favorite animated films. I'm going to end up writing about it in somewhat technical terms, but what makes the film great are the feelings that it evokes.

The design hits the sweet spot between realism and caricature. The designs are realistic enough to support the emotions and events in the story, but still caricatured enough to allow for cartoonyness in the acting and the timing.

One of the things that make shapes appealing in animation is their pliability. Flesh yields. We hug things whose surfaces are pliable, whether it's other humans, pets or stuffed toys. We don't hug rocks. There's a softness to how these characters are drawn and move that's enormously appealing.

I'm especially impressed by this film's use of visual metaphor. You've got blooming flowers tied to puberty and boys as bees flying towards the flowers as a way of communicating sexual attraction. You've got floating and flying to the moon as metaphors for romance. One sister shatters like glass as an expression of shock and pain. The jealous sister transforms into an ape, a jackal, a pterodactyl and a shark to show the animal rage she feels towards her sibling.

We've all seen cartoons where a character's spirit separates from its body and somebody stuffs it back in. Usually it's played for comedy, but here it's played for desperation. This and the shattering glass take could easily fit into a Tex Avery cartoon with very different results, which shows how flexible the idea of visual metaphor can be and how powerful animation really is as a medium. We've got tools, but we tend to do the same things with them over and over again. This film shows us that the tools are more versatile than we know.

Which leads me to what I admire most about this film: its emotional range. Animated shorts have a tendency to be all one thing. They're humorous or satirical or political or tragic. Often, an entire short is a build-up to a single ending gag. This film manages to encompass many moods and emotions in less than 8 minutes. Furthermore, they're emotions that are universally understood. This film talks to everyone, not just animation fans.

The time and effort required to make a cartoon forces independent animators to be miniaturists. They're stuck putting their stories on a small canvas. Anna and Bella shows how much is possible to fit on that canvas and I wonder why we so often settle for less.

This is one of my favorite animated films. I'm going to end up writing about it in somewhat technical terms, but what makes the film great are the feelings that it evokes.

The design hits the sweet spot between realism and caricature. The designs are realistic enough to support the emotions and events in the story, but still caricatured enough to allow for cartoonyness in the acting and the timing.

One of the things that make shapes appealing in animation is their pliability. Flesh yields. We hug things whose surfaces are pliable, whether it's other humans, pets or stuffed toys. We don't hug rocks. There's a softness to how these characters are drawn and move that's enormously appealing.

I'm especially impressed by this film's use of visual metaphor. You've got blooming flowers tied to puberty and boys as bees flying towards the flowers as a way of communicating sexual attraction. You've got floating and flying to the moon as metaphors for romance. One sister shatters like glass as an expression of shock and pain. The jealous sister transforms into an ape, a jackal, a pterodactyl and a shark to show the animal rage she feels towards her sibling.

We've all seen cartoons where a character's spirit separates from its body and somebody stuffs it back in. Usually it's played for comedy, but here it's played for desperation. This and the shattering glass take could easily fit into a Tex Avery cartoon with very different results, which shows how flexible the idea of visual metaphor can be and how powerful animation really is as a medium. We've got tools, but we tend to do the same things with them over and over again. This film shows us that the tools are more versatile than we know.

Which leads me to what I admire most about this film: its emotional range. Animated shorts have a tendency to be all one thing. They're humorous or satirical or political or tragic. Often, an entire short is a build-up to a single ending gag. This film manages to encompass many moods and emotions in less than 8 minutes. Furthermore, they're emotions that are universally understood. This film talks to everyone, not just animation fans.

The time and effort required to make a cartoon forces independent animators to be miniaturists. They're stuck putting their stories on a small canvas. Anna and Bella shows how much is possible to fit on that canvas and I wonder why we so often settle for less.

Sunday, May 14, 2006

N.Y. Institute of Technology, Part 1

NYIT in Westbury, Long Island, is a school that had an animation studio attached to it for a while. While the studio and its films are not widely remembered, a lot of very interesting people passed through the place.

John Celestri is a fellow New Yorker, though I didn't meet him until we were both in Toronto. He was at NYIT in the '70's and I've asked him to share some of his memories.

John’s Blog Memories of NYIT: Part 1

Both Mark Mayerson and I have separately come to the understanding that historically what went on at the New York Institute of Technology during the mid- to late-1970s was the hidden ending to both the Paramount and Terrytoon studios.

I was on staff there from March of 1975 to May of 1976.

My additional observation is that it was also the hidden birth of computer animation as we know it today. The fact is that Tubby the Tuba was put into production so that Dr. Alexander Schure (who basically owned and ran NYIT) could study the process of putting together an animated feature and see what technical problems needed to be surmounted by a computer. As Tubby was being produced by a crew of semi-retired animators headed by Chuck Harriton and John Gentilella, a separate crew on the far side of the Long Island campus (headed by young Edwin Catmull) was busy experimenting with ways to draw and color pictures on a computer screen.

(Here's a paper by Ed Catmull on the problems of computer assisted animation and an interview with Catmull about his time at NYIT.)

When the traditional work on Tubby was completed, a selected crew of the Paramount and Terrytoon animators were reassigned to the computer crew. Among them were John Gentilella, Dante Barbetta, and Earl James. Their task was to draw and animate objects with the tools the computer crew was developing, showing them what difficulties they had using the tools.

The eventual direct result of all this experimentation is the creation of both Disney’s CAPS system and Pixar’s CGI systems. Just the thought of this major historical connection makes my head spin.

John Celestri is a fellow New Yorker, though I didn't meet him until we were both in Toronto. He was at NYIT in the '70's and I've asked him to share some of his memories.

John’s Blog Memories of NYIT: Part 1

Both Mark Mayerson and I have separately come to the understanding that historically what went on at the New York Institute of Technology during the mid- to late-1970s was the hidden ending to both the Paramount and Terrytoon studios.

I was on staff there from March of 1975 to May of 1976.

My additional observation is that it was also the hidden birth of computer animation as we know it today. The fact is that Tubby the Tuba was put into production so that Dr. Alexander Schure (who basically owned and ran NYIT) could study the process of putting together an animated feature and see what technical problems needed to be surmounted by a computer. As Tubby was being produced by a crew of semi-retired animators headed by Chuck Harriton and John Gentilella, a separate crew on the far side of the Long Island campus (headed by young Edwin Catmull) was busy experimenting with ways to draw and color pictures on a computer screen.

(Here's a paper by Ed Catmull on the problems of computer assisted animation and an interview with Catmull about his time at NYIT.)

When the traditional work on Tubby was completed, a selected crew of the Paramount and Terrytoon animators were reassigned to the computer crew. Among them were John Gentilella, Dante Barbetta, and Earl James. Their task was to draw and animate objects with the tools the computer crew was developing, showing them what difficulties they had using the tools.

The eventual direct result of all this experimentation is the creation of both Disney’s CAPS system and Pixar’s CGI systems. Just the thought of this major historical connection makes my head spin.

Saturday, May 13, 2006

Animation in The Pied Piper of Basin Street

One of the interesting things about the Lantz studio in the 1940's is the difference in the ability of the animators. At Disney, Warners and MGM, the animators were more consistent in their abilities. In this cartoon, you've got Disney veterans like Dick Lundy and Grim Natwick side by side with Lantz stalwarts like Les Kline and Paul Smith. There's a wide variation in animation quality in this cartoon, but Culhane has done a pretty good job of casting the animators to play to their strengths and not let their weaknesses hurt the cartoon.

Emery Hawkins has only five shots, but shot 39 may be the nicest acting shot in the film. It's got everything Hawkins is known for: strongly rhythmic drawing and posing, broad action, sharp timing, and extreme flexibility. There's a looseness to Hawkins' animation that makes his characters seem far more alive than the work by Les Kline that leads into the shot. Kline's drawings aren't nearly as appealing and his conception of movement is far simpler. You can tell there's a higher proportion of inbetweens in Kline's work than in Hawkins'. Kline's shapes don't change as radically and his poses are pretty mundane. They don't have a strong line of action.

Pat Matthews' animation is not as broad as Hawkins', but the sense of design in his drawing is strong and he's a very capable animator. His introductory scenes with the Mayor make the character of the piper seem likable and are well acted.

LaVerne Harding concentrates mostly on the Mayor character. She's got only a couple of other miscellaneous shots. Her drawing is strong and her acting is good, but her timing isn't as daring as Hawkins'.

Paul Smith's best work in this cartoon is at the end. The shots are short and there's a single, broad action taking place in each of them. Maybe I'm being unfair to him, but I wonder if he had strong character layouts to work with, as the shots look better than I would expect.

Don Williams does some pretty daring things with cropping and perspective in shot 69. Most of the time, the characters in this cartoon are at eye level, a comfortable distance away from the camera and surrounded by lots of negative space to give them a clear silhouette. In the opening shot and this one, Williams animates characters in perspective. Shot 69 is a vertical pan, but what really catches my eye is how close the mice are to the camera as they leap down the button panel and how they're drawn from a high angle. The staging in this shot is unlike any other in the cartoon. Williams also gives the mice an attractive fleshiness and follow-through during their leaps.

Dick Lundy was soon to be directing at Lantz and may only have been filling in as an animator until that happened. His work here rivals Hawkins. The lady mouse's dialogue in shot 3 is handled well and the cheese slicing in scene 4 is well-timed. Having come from Disney, there's no question that his drawing and posing are strong.

Grim Natwick has little to do here. Only five shots, and four of them are pretty short. The old woman in scene 49 resembles the old woman in the Flip the Frog shorts that Natwick worked on for the Iwerks studio. For the old woman, he uses staggered doping of drawings to get the animation to vibrate and the poses are pretty broad.

I think that Natwick's involvement in Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs has skewed our perception of his career. I think that Snow White and Princess Glory from Gulliver's Travels are atypical of Natwick's work, which really tends to be quite broad and cartoony. That's true of his work at Fleischer and Iwerks in the early '30's, his work at Lantz in the '40's, his TV commercials in the '50's and even his work on Raggedy Ann and Andy in 1977.

I hope that all of the above makes sense. I find it a struggle to use words to talk about animation and one of the things I wish is that we had a better vocabulary to do it.

Emery Hawkins has only five shots, but shot 39 may be the nicest acting shot in the film. It's got everything Hawkins is known for: strongly rhythmic drawing and posing, broad action, sharp timing, and extreme flexibility. There's a looseness to Hawkins' animation that makes his characters seem far more alive than the work by Les Kline that leads into the shot. Kline's drawings aren't nearly as appealing and his conception of movement is far simpler. You can tell there's a higher proportion of inbetweens in Kline's work than in Hawkins'. Kline's shapes don't change as radically and his poses are pretty mundane. They don't have a strong line of action.

Pat Matthews' animation is not as broad as Hawkins', but the sense of design in his drawing is strong and he's a very capable animator. His introductory scenes with the Mayor make the character of the piper seem likable and are well acted.

LaVerne Harding concentrates mostly on the Mayor character. She's got only a couple of other miscellaneous shots. Her drawing is strong and her acting is good, but her timing isn't as daring as Hawkins'.

Paul Smith's best work in this cartoon is at the end. The shots are short and there's a single, broad action taking place in each of them. Maybe I'm being unfair to him, but I wonder if he had strong character layouts to work with, as the shots look better than I would expect.