Showing posts with label Greg Duffell. Show all posts

Showing posts with label Greg Duffell. Show all posts

Wednesday, January 01, 2014

Richard Williams Documentary in Toronto

Kevin Schreck's documentary on the making of Richard Williams' The Cobbler and the Thief, Persistence of Vision, will be playing several times at the Bloor Hot Docs Cinema in January. Schreck will be appearing at several screenings via Skype and two artists who worked on the film, Greg Duffell and Tara Donovan, will be present in person.

The film first screened in Toronto last August as part of TAAFI. I reviewed it here. I highly recommend the film and the opportunity to hear from Schreck, Duffell and Donovan, all of whom also accompanied the TAAFI screening.

Here are the dates:

Fri, Jan 10 6:30 PM*

Sat, Jan 11 1:00 PM*

Sun, Jan 12 3:30 PM*

Mon, Jan 13 6:30 PM

Wed, Jan 15 4:00 PM

Thu, Jan 16 3:45 PM

The asterisks indicate which screenings that Schreck, Duffell and Donovan will appear.

Friday, August 02, 2013

Persistence of Vision

Richard Williams

I will write an entry about TAAFI's third day, but Kevin Schreck's documentary Persistance of Vision, which screened at TAAFI, deserves an entry of its own. The film is a chronicle of the making and unmaking of the Richard Williams' feature The Cobbler and the Thief. Williams began the film as an adaptation of stories featuring the mullah Nasruddin written by Idries Shah. A falling out with the Shah family led to the reworking of the story to eliminate the Nasruddin character and a cobbler became the new focus of the film.

Williams financed the film out of profits made from his studio's commercial work. After the success of Williams' contribution to the animation of Who Framed Roger Rabbit, Warner Bros. agreed to finance his feature. When Williams failed to deliver the film on time, Warner Bros. decided it was better to drop the project and collect the completion insurance, which put the ownership of the film in the hands of The Completion Bond Company. At that point, the film had been in production for 24 years.

Stuck with a film they didn't want, the bond company took it away from Williams and had it completed in the cheapest, fastest way possible. They hoped to salvage something financially by bowdlerizing the film to make it look like other animated features of the time. The film, released as Arabian Knight, was a failure and Williams withdrew from active production to lecture, write The Animator's Survival Kit, and to work on personal projects.

That's a very bare outline of events, but the man at the center of it, Richard Williams, is a huge contradiction: he elevated the art of animation but was the author of his own misfortune. Schreck's film explores both of these aspects of Williams' career by interviewing many people who worked on the film and using footage of Williams himself from interviews he gave over the years.

Left to right: Ken Harris, Grim Natwick, Art Babbitt, Richard Purdom, Richard Williams

Williams understood that the men who created character animation were getting on in years and that their art would die with them. At his own expense, he brought animators Art Babbitt, Ken Harris, and Grim Natwick to his studio to train his staff. These veterans of Disney and Warner Bros. gave their knowledge freely as well as contributing to the studio's output. Williams himself was a perfectionist who demanded the best possible work from his staff. While he was often a difficult boss, those who worked for him acknowledge the opportunity he gave them to grow as artists.

Left to right: Ben McEvoy, Kevin Schreck, Tara Donovan, Greg Duffell. Donovan and Duffell both drew inbetweens on the Williams feature 17 years apart.

After the screening, Kevin Schreck made the comment that Williams had the sensibility of a painter working in film rather than the sensibility of a film maker. That crystallized my thinking on Williams. While he brought over veteran animators and idolized Milt Kahl, it's interesting that over the course of the production, he never brought in veteran story men like Bill Peet, Mike Maltese or Bill Scott. He never consulted with directors like Wilfred Jackson, Dave Hand or John Hubley. At no time did he hire a famous screenwriter or novelist. He was interested in creating better animation, but he was uninterested in what the animation was there to serve.

Williams treated content as an excuse to create elaborate visuals, but he didn't much care what the content was and may not have been able to tell the difference between good and bad content. In this way, he was perfectly suited to the commercials his studio turned out. He was lucky that during that period, British ad agencies were writing literate and witty ads. The combination of their content and his astounding artwork made his commercials the best in the world.

But when the content was mediocre, as it was in his feature Raggedy Ann and Andy or in The Cobbler and the Thief, the result was an elaborateness that wasn't justified. Character designs were overly complicated and had a multiplicity of colours. Layouts used tricky perspectives. The inevitable result was that artists could only work at a snail's pace, driving up the budget and jeopardizing delivery. The detail overwhelmed the flimsy stories and the films collapsed under their own weight.

Someone in the documentary revealed that during the period when Warner Bros. was financing the film, Williams was still creating storyboards. That was twenty years into the project. It was obvious that Williams considered story an inconvenience; it had to be done so there would be something to draw. In the panel discussion after the film, Greg Duffell recalled that there were mornings where Williams had to create sequences off the cuff in order to supply Ken Harris with work. There was never a structured story, just sequences that tickled Williams' fancy. The visuals were what Williams cared about.

Schreck's film encompasses the heroic Williams and the self-destructive Williams. Williams is animation's Erich Von Stroheim, making an impossibly long version of Greed. Or maybe Williams is Captain Ahab, inspiring his crew to pursue the white whale but leading them all to destruction. Williams set out to make a masterpiece, to show the world animation as it had never been done before. Those parts of his film that survive are unlike anything else that's been done. But being different and being worthwhile are not the same. Williams chose to work in a medium where the audience expects a story that evokes emotions, but Williams saw story as a necessary evil instead of the heart of the project.

This documentary is a major work of animation history. Schreck has been traveling with it to festivals all around the continent. I don't know if the film will be picked up for distribution as clearing the rights to various clips would be expensive and time consuming. For now, festivals may be the only way to see the film, so you'll have to seek it out.

Williams' career has undoubtedly been a benefit to the entire animation industry, but his success with audiences was greater when others created the content that was the basis for his work.

Tuesday, July 30, 2013

TAAFI Roundup Day 1

Anyone who has attended an animation festival knows that the cascade of talks and films tend to blur together. In addition, TAAFI had three sessions running simultaneously each day. It's possible for someone to have attended and experienced a completely different festival, so don't take this as a definitive review of TAAFI, merely my own personal impressions.

David Silverman, a director on The Simpsons, gave the keynote address on the series. Someone asked about table reads and punching up the script and Silverman revealed that the script was punched up at least four times, the final time after footage was already in colour. He mentioned that people suggested more efficient ways of working, but his attitude was that the show was the most successful animated series in history, so why mess with a good thing?

This was followed by a state of the industry panel. Ben McEvoy, one of TAAFI's founders moderated and asked if the broadcasting was dying, with so many people cutting their cable subscriptions. Predictably, the broadcasters on the panel said no. Whether they believe this or were trying to project confidence, I don't know.

Later, there was a panel "From Napkin Sketch to Green Light," about pitching shows and getting them to air. Someone on the panel said it could take five years to go from pitch to a show, and I thought to myself that if broadcasting wasn't dying now (and I think it is), who knows where it would be in five years? Pitching shows to conventional broadcasters and cable channels now is a questionable proposition, as their financial model is deteriorating rapidly.

I have an axe to grind here, but it was clear from this panel that ideas should not be fully developed, as broadcasters like to shape shows to their needs, and a broadcast executive emphasized that even if he liked a pitch, he still had to sell it to those higher up in his company. The combination of these two things is the reason that I personally discourage people from pitching shows. Any creator worth his or her salt is going to want to explore their idea and nail things down. This is precisely what broadcasters don't want. There are legitimate reasons, such as needing a show to be suitable to a particular demographic, but there is also the vanity of business people who think that their ideas are as good as anybody's. If this was true, they wouldn't need to take pitches and would create their shows in-house. Furthermore, after contorting an idea to please a development executive, the executive doesn't have the authority to put the show into production but has to convince the bosses, who are likely to contort the show even more. While this ugly process proceeds, the creator is being paid peanuts in development money while the broadcast people are on salary.

The game is stacked heavily against creators, which is why I encourage people to get their work to an audience in a more direct fashion: as prose or as comics distributed on the internet. Besides establishing ownership of the property (something you would have to give up to a production company or broadcaster), it allows a creator to thoroughly explore the idea and develop it without interference. Finally, should the property attract an audience, that gives the creator increased leverage in dealing with broadcaster interest.

The business we're in is very simple, really. It's all about attracting an audience, the larger the better. That audience gets monetized though advertising, subscriptions, pay-per-view, merchandise, etc. and that's what finances the whole shebang. If you've built an audience, that makes you and your property valuable. People who want access to your audience will come to you. Pitching will be unnecessary and instead they'll be making you offers.

There was a panel on funding yourself which I had to miss as it ran concurrently with a panel I moderated on portfolios and self-promotion. I really wanted to see it.

My panel had Lance Lefort of Arc, Darin Bristow of Nelvana, Patti Mikula of XMG Studio and Peter Nalli of Rune Entertainment talking about the best way to organize your material when applying for work. These days studios prefer links to any physical media. Reels should be short with the best material up front. Applicants should know about the companies before applying so that they know they're showing suitable material. Resumes should be no longer than 2 pages and cover letters a single page. All stressed that attitude was as important as skills, as they were looking for people who would fit into existing teams and be pleasant to work with.

The day ended with three talks. Mark Jones and Sean Craig of Seneca College talked about how the school had worked on professional productions, particularly those made by Chris Landreth.

Jason Della Rocca gave a fabulous talk relating Darwinian evolution to the changing nature of the media. As I have an interest in evolutionary psychology and business, it was right up my alley. He talked about how people assume that the present environment extends infinitely into the future without disruption and how inevitable disruption catches people off guard. He talked about the importance of variation in an uncertain environment as the only way to discover what would work in new conditions. Failure was a necessity in order to gain knowledge but the failure had to be small enough as to not destroy an enterprise. Della Rocca mentioned that Angry Birds was the fiftieth project of the creators and that nobody remembered the previous forty nine. He talked about how the highest quality inevitably came from those who put out the greatest quantity, precisely because that quantity (including failures) gave them more information about what worked in a given environment. The talk could be boiled down to "fail fast and cheap." Right now, Hollywood is betting everything on tentpoles that cost $100 million plus (meaning "slow and expensive") and even Lucas and Spielberg are warning that movies are vulnerable to a financial collapse as a result.

The last speaker of the day was veteran animator Greg Duffell, who talked about timing. In the past, directors would time entire films down to the frame as a way of guaranteeing synchronization with music that was being written while the animation was being done. Duffell talked about how this had fallen by the wayside and that what animation directors do today bears very little resemblance to what they previously did. Duffell gave a longer version of this talk to the Toronto Animated Image Society several years ago and I wish that TAAFI had allowed more time for this important talk.

Coming up will be reflections on days two and three of the festival.

David Silverman

This was followed by a state of the industry panel. Ben McEvoy, one of TAAFI's founders moderated and asked if the broadcasting was dying, with so many people cutting their cable subscriptions. Predictably, the broadcasters on the panel said no. Whether they believe this or were trying to project confidence, I don't know.

Later, there was a panel "From Napkin Sketch to Green Light," about pitching shows and getting them to air. Someone on the panel said it could take five years to go from pitch to a show, and I thought to myself that if broadcasting wasn't dying now (and I think it is), who knows where it would be in five years? Pitching shows to conventional broadcasters and cable channels now is a questionable proposition, as their financial model is deteriorating rapidly.

I have an axe to grind here, but it was clear from this panel that ideas should not be fully developed, as broadcasters like to shape shows to their needs, and a broadcast executive emphasized that even if he liked a pitch, he still had to sell it to those higher up in his company. The combination of these two things is the reason that I personally discourage people from pitching shows. Any creator worth his or her salt is going to want to explore their idea and nail things down. This is precisely what broadcasters don't want. There are legitimate reasons, such as needing a show to be suitable to a particular demographic, but there is also the vanity of business people who think that their ideas are as good as anybody's. If this was true, they wouldn't need to take pitches and would create their shows in-house. Furthermore, after contorting an idea to please a development executive, the executive doesn't have the authority to put the show into production but has to convince the bosses, who are likely to contort the show even more. While this ugly process proceeds, the creator is being paid peanuts in development money while the broadcast people are on salary.

The game is stacked heavily against creators, which is why I encourage people to get their work to an audience in a more direct fashion: as prose or as comics distributed on the internet. Besides establishing ownership of the property (something you would have to give up to a production company or broadcaster), it allows a creator to thoroughly explore the idea and develop it without interference. Finally, should the property attract an audience, that gives the creator increased leverage in dealing with broadcaster interest.

The business we're in is very simple, really. It's all about attracting an audience, the larger the better. That audience gets monetized though advertising, subscriptions, pay-per-view, merchandise, etc. and that's what finances the whole shebang. If you've built an audience, that makes you and your property valuable. People who want access to your audience will come to you. Pitching will be unnecessary and instead they'll be making you offers.

There was a panel on funding yourself which I had to miss as it ran concurrently with a panel I moderated on portfolios and self-promotion. I really wanted to see it.

My panel had Lance Lefort of Arc, Darin Bristow of Nelvana, Patti Mikula of XMG Studio and Peter Nalli of Rune Entertainment talking about the best way to organize your material when applying for work. These days studios prefer links to any physical media. Reels should be short with the best material up front. Applicants should know about the companies before applying so that they know they're showing suitable material. Resumes should be no longer than 2 pages and cover letters a single page. All stressed that attitude was as important as skills, as they were looking for people who would fit into existing teams and be pleasant to work with.

The day ended with three talks. Mark Jones and Sean Craig of Seneca College talked about how the school had worked on professional productions, particularly those made by Chris Landreth.

Jason Della Rocca gave a fabulous talk relating Darwinian evolution to the changing nature of the media. As I have an interest in evolutionary psychology and business, it was right up my alley. He talked about how people assume that the present environment extends infinitely into the future without disruption and how inevitable disruption catches people off guard. He talked about the importance of variation in an uncertain environment as the only way to discover what would work in new conditions. Failure was a necessity in order to gain knowledge but the failure had to be small enough as to not destroy an enterprise. Della Rocca mentioned that Angry Birds was the fiftieth project of the creators and that nobody remembered the previous forty nine. He talked about how the highest quality inevitably came from those who put out the greatest quantity, precisely because that quantity (including failures) gave them more information about what worked in a given environment. The talk could be boiled down to "fail fast and cheap." Right now, Hollywood is betting everything on tentpoles that cost $100 million plus (meaning "slow and expensive") and even Lucas and Spielberg are warning that movies are vulnerable to a financial collapse as a result.

Greg Duffel explaining spacing charts

The last speaker of the day was veteran animator Greg Duffell, who talked about timing. In the past, directors would time entire films down to the frame as a way of guaranteeing synchronization with music that was being written while the animation was being done. Duffell talked about how this had fallen by the wayside and that what animation directors do today bears very little resemblance to what they previously did. Duffell gave a longer version of this talk to the Toronto Animated Image Society several years ago and I wish that TAAFI had allowed more time for this important talk.

Coming up will be reflections on days two and three of the festival.

Monday, September 06, 2010

The Provenance of a Painting

(Updated at the bottom.)

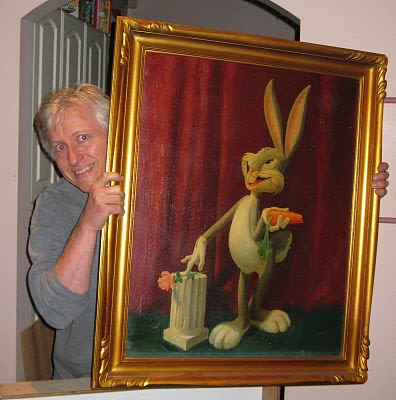

Leon Schlesinger was the producer and owner of the Looney Tunes and Merrie Melodies that were released through Warner Bros. While his studio had cartoon stars like Porky Pig and Daffy Duck, Bugs Bunny surpassed both of them to become a major hit with audiences. As a result, Schlesinger had this painting made and hung in his office.

The artist is unknown, though it is likely John Didrik Johnsen, the background painter who worked in the Tex Avery unit.

Schlesinger sold out to Warner Bros. in the mid 1940s and his office contents were put out with the trash. Story man Michael Maltese was driving home and saw this painting in the garbage and took it. He kept it for the rest of his life.

Greg Duffell started at the Richard Williams studio when he was 17 years old. He was intensely interested in animation and just as intensely interested in its history. Duffell was lucky to be at the Williams studio when Williams hired veteran animators Ken Harris, Grim Natwick and Art Babbitt to work and to educate the staff.

When Duffell visited Maltese in California in the 1970s, he saw the painting in his home. Maltese passed away several years later, and his family put the painting up for auction. Duffell won the bid.

Last Saturday, I visited Greg with Thad Komorowski and Bob Jaques. We spent a pleasant afternoon talking about animation and towards the end, Greg hauled out some of the vintage animation art he's acquired over the years. When I was about to leave, Greg asked me to stay for just another few minutes while he showed one more item. He brought out the painting pictured above.

I've seen a lot of animation art but this piece had a different effect on me. Maybe because it was painted, maybe because of its size, but I think it goes deeper. I've been to museums and seen paintings by masters and while I can admire their beauty and craft, I don't have the same emotional connection to the work. Maybe it's nostalgia for my childhood or a wish to have been part of the business during the time the painting was created, but the painting was akin to a religious relic. It is an artifact from a vanished golden age, evidence of what animation once was and no longer is.

Update: Michael Barrier has printed a photo of Michael Maltese with the painting and supplied more information about the creation of the painting and how it came into Maltese's possession.

Leon Schlesinger was the producer and owner of the Looney Tunes and Merrie Melodies that were released through Warner Bros. While his studio had cartoon stars like Porky Pig and Daffy Duck, Bugs Bunny surpassed both of them to become a major hit with audiences. As a result, Schlesinger had this painting made and hung in his office.

The artist is unknown, though it is likely John Didrik Johnsen, the background painter who worked in the Tex Avery unit.

Schlesinger sold out to Warner Bros. in the mid 1940s and his office contents were put out with the trash. Story man Michael Maltese was driving home and saw this painting in the garbage and took it. He kept it for the rest of his life.

Greg Duffell started at the Richard Williams studio when he was 17 years old. He was intensely interested in animation and just as intensely interested in its history. Duffell was lucky to be at the Williams studio when Williams hired veteran animators Ken Harris, Grim Natwick and Art Babbitt to work and to educate the staff.

When Duffell visited Maltese in California in the 1970s, he saw the painting in his home. Maltese passed away several years later, and his family put the painting up for auction. Duffell won the bid.

Last Saturday, I visited Greg with Thad Komorowski and Bob Jaques. We spent a pleasant afternoon talking about animation and towards the end, Greg hauled out some of the vintage animation art he's acquired over the years. When I was about to leave, Greg asked me to stay for just another few minutes while he showed one more item. He brought out the painting pictured above.

I've seen a lot of animation art but this piece had a different effect on me. Maybe because it was painted, maybe because of its size, but I think it goes deeper. I've been to museums and seen paintings by masters and while I can admire their beauty and craft, I don't have the same emotional connection to the work. Maybe it's nostalgia for my childhood or a wish to have been part of the business during the time the painting was created, but the painting was akin to a religious relic. It is an artifact from a vanished golden age, evidence of what animation once was and no longer is.

Update: Michael Barrier has printed a photo of Michael Maltese with the painting and supplied more information about the creation of the painting and how it came into Maltese's possession.

Saturday, February 07, 2009

Soho Square

What started out as Michael Sporn trying to identify a boy in a picture has developed (in the comments) into several lengthy reminiscences of the Dick Williams Studio in Soho Square in 1973. Commenters who were there include Greg Duffell, Suzanne Wilson and Børge Ring.

At the time of the photo, Williams had veteran American animators Ken Harris, Grim Natwick and Art Babbitt working at the studio. Babbit spent weeks teaching classes in animation technique to the Williams crew. The people associated with Williams at this time went on to become leaders of British animation and Dick Williams deserves much credit for providing them with such a singular education.

At the time of the photo, Williams had veteran American animators Ken Harris, Grim Natwick and Art Babbitt working at the studio. Babbit spent weeks teaching classes in animation technique to the Williams crew. The people associated with Williams at this time went on to become leaders of British animation and Dick Williams deserves much credit for providing them with such a singular education.

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)