The Ottawa International Animation Festival has posted the list of films that have been accepted. There is also a list of retrospectives and other screenings.

Michael Sporn has posted the first part of John Hubley's storyboard for Cockaboody.

Keith Lango has written a three part essay entitled "The Fool's Errand," talking about strategies for making independent computer animated shorts. Part 1, Part2, Part 3.

Kevin Langley has put up some slow motion videos of Bobe Cannon's animation from the Chuck Jones cartoon The Dover Boys. Keith Lango adds his thoughts about Cannon's animation here.

Hans Perk has resumed putting up drafts for Disney shorts. Here's Moving Day, Polar Trappers, and The Dognapper.

Didier Ghez has also posted some Disney drafts from the collection of Mark Kausler. Here are Pioneer Days, Midnight in a Toy Shop, Winter, and Playful Pan.

Mark Kausler's own blog has an evaluation of the various studios that made Krazy Kat cartoons over the years.

Michael Barrier revisits The Iron Giant. It's not possible to link to specific entries on Barrier's blog, but it was posted on July 25.

And a reminder that Volume 1 of the Popeye DVD set is now available. All the Popeye cartoons from 1933 to 1938 restored from original negatives. Furthermore, the Woody Woodpecker set, including cartoons by Tex Avery, Shamus Culhane, Dick Lundy and Bill Nolan, is also available.

Tuesday, July 31, 2007

Monday, July 30, 2007

Two Trailers; Two Tragedies

While I'm in favour of copyright, allowing creative artists and their heirs to financially benefit from their creations, what do you do in cases where the heirs have no reservation about trashing the work they own in exchange for a few bucks?

I am not under the illusion that Alvin and the Chipmunks is, or ever was, great art. It started out as a novelty 45 rpm record by Ross Bagdasarian, a musician behind other novelty records of the time including "Witch Doctor" and "Come on-a My House." The chipmunk record took off and led to an early animated TV series and some merchandising. Bagdasarian was no Cole Porter, but at least his work was inoffensive.

What is it about toilet humour and animated films? We've gone from fart jokes to characters defecating on screen in Open Season to characters eating each other's waste material now. When did family films look to John Waters and Pink Flamingoes as a model? When did a porn fetish become children's entertainment? And who, at the MPAA, approved this trailer for all audiences?

My objection is not to the obscenity, it's the complete and total lack of imagination. In a medium where characters can do anything, they choose to do this? With the entire history of film comedy to draw on, this is the best they could do?

(And what about the general cheapness of the trailer? No shot combining Jason Lee with the animated characters? Not even an over the shoulder shot? Not only can't they write, they don't know diddley about directing either.)

No doubt the Bagdasarian family is hoping that this film spins off sequels and perhaps a new TV version. Much as I like to support creatives, I hope this project fails in a big enough way to bury the chipmunks for another generation.

Over at Blue Sky, they're adapting Dr. Seuss's Horton Hears a Who. No question that the art direction is attractive and they've done a great job of making Seuss's characters believably dimensional. However, good looking visuals are not enough. Seuss's language was at least half the appeal of his work and it's totally missing here. How many of you can recite some of Green Eggs and Ham by heart?

They've also failed to capture Horton's personality. Jim Carrey is fundamentally miscast as Horton, a character who can best be described as a plodder. Carrey is too high energy. The animators have no choice but to move Horton in unelephant-like ways in order to match Carrey's reading.

Furthermore, whoever is behind the screenplay doesn't understand how to write for animation. There's way too much dialogue and the animators are stuck looking for gestures to keep the characters alive while the dialogue drones on. I don't envy the animator stuck with that Steve Carell scene. It's a tough challenge, but he or she is making it worse by using gestures to illustrate words and phrases as opposed to thoughts. The character is overly busy and the gestures are mostly empty of emotion.

I once had great hopes for Blue Sky. Except for the first Ice Age, the visuals have accompanied structurally flawed stories. There is no question that they bring an enormous amount of art talent to each of their films, but there's a sharp divide between their visuals and their scripts. Either Fox is not giving Blue Sky enough freedom to rework scripts into animatable form, or Blue Sky itself just has no talent for story. They wouldn't be the first studio to have that problem.

These projects make it hard to justify the existence of copyright past a creator's death except for financial benefits. I can't believe that if the chipmunks or Seuss's work were public domain, we'd be doing any worse in the way of film adaptations. It's clear that the heirs don't understand what they own. What a shame that we have to witness the degradation of any creator's legacy at the hands of his or her heirs.

Deanna Marsigliese

This Thursday, August 2, in Toronto, from 7-10 p.m. The Labyrinth Bookstore will have its second art show premiere featuring the work of designer Deanna Marsigliese. The store is located at 386 Bloor Street West, 2 blocks west of the Spadina subway station. The Labyrinth has published a book collection of her work called The Art of Deanna Marsigliese. You can read more about her here and get information about ordering the book here.

This Thursday, August 2, in Toronto, from 7-10 p.m. The Labyrinth Bookstore will have its second art show premiere featuring the work of designer Deanna Marsigliese. The store is located at 386 Bloor Street West, 2 blocks west of the Spadina subway station. The Labyrinth has published a book collection of her work called The Art of Deanna Marsigliese. You can read more about her here and get information about ordering the book here.If you're in the neighborhood before Thursday, there's still time to catch the first show, an exhibit of sketches done on the subway by Bobby Chiu and Kei Acedera. Their work is available at The Labyrinth in their self-published book Subway Sketches.

Saturday, July 28, 2007

Friday, July 27, 2007

Pinocchio Part 18A

This sequence exposes one of the weaknesses in the story, one which Disney inherited from the original book. In a story where a fox and a cricket speak, you've got to really be obvious to let the audience know that the donkeys aren't supposed to and that those that can still speak started out as boys.

Alexander is the only character in the Pleasure Island sequence outside of Pinocchio, Lampwick, the Coachman and Jiminy who has dialogue. Looking at him, I can't help but think of Tom Stoppard's play Rosencrantz and Guildenstern are Dead, which takes two minor characters from Hamlet and reimagines the play from their viewpoint, or The Wind Done Gone, a version of Gone With the Wind told from the viewpoint of Scarlett O'Hara's mulatto half sister. You could make a whole other film that was Alexander's story, leading up to Pleasure Island and even following his life as a donkey.

When I upload the next sequence, you'll see that this sequence is numbered in such a way to suggest that it originally followed Lampwick's transformation into a donkey. It's interesting that they felt the need to reveal this to Jiminy before Pinocchio experiences it. Maybe it was a way of preparing the children in the audience for what is the most terrifying sequence in all of Disney. Or maybe Jiminy's discovery coming after Lampwick's transformation would be an anti-climax.

Woolie Reitherman takes over Jiminy. His work isn't as crisp as the other animators who have handled the character earlier. Eric Larson, known for his animal animation, is responsible for the best donkey shots. He certainly evokes sympathy for the donkeys. Charles Nichols continues with the coachman. It's interesting to see Bill Shull here, taking some donkey shots, as he usually was Tytla's assistant and animated scenes on Tytla sequences.

Alexander is the only character in the Pleasure Island sequence outside of Pinocchio, Lampwick, the Coachman and Jiminy who has dialogue. Looking at him, I can't help but think of Tom Stoppard's play Rosencrantz and Guildenstern are Dead, which takes two minor characters from Hamlet and reimagines the play from their viewpoint, or The Wind Done Gone, a version of Gone With the Wind told from the viewpoint of Scarlett O'Hara's mulatto half sister. You could make a whole other film that was Alexander's story, leading up to Pleasure Island and even following his life as a donkey.

When I upload the next sequence, you'll see that this sequence is numbered in such a way to suggest that it originally followed Lampwick's transformation into a donkey. It's interesting that they felt the need to reveal this to Jiminy before Pinocchio experiences it. Maybe it was a way of preparing the children in the audience for what is the most terrifying sequence in all of Disney. Or maybe Jiminy's discovery coming after Lampwick's transformation would be an anti-climax.

Woolie Reitherman takes over Jiminy. His work isn't as crisp as the other animators who have handled the character earlier. Eric Larson, known for his animal animation, is responsible for the best donkey shots. He certainly evokes sympathy for the donkeys. Charles Nichols continues with the coachman. It's interesting to see Bill Shull here, taking some donkey shots, as he usually was Tytla's assistant and animated scenes on Tytla sequences.

Wednesday, July 25, 2007

IDT Buys Comics Publisher; Plans Content for Mobile Phones

I wrote earlier about IDT's foray into the animation business. The company knew nothing about animation but publicly announced that they were going to be "Pixar on steroids." Their one feature was Everyone's Hero, a film that grossed less than $15 million in North America. They bailed out of the animation business, selling their holdings to Liberty Media.

They are now trying to get into original content for mobile phones and have purchased comic book publisher IDW to help them create content.

I admit to being strongly biased against IDT for what they did to my TV series and the animation business in general. However, you may want to read this commentary on the current state of their business by someone who wasn't a victim of their incompetence.

They are now trying to get into original content for mobile phones and have purchased comic book publisher IDW to help them create content.

I admit to being strongly biased against IDT for what they did to my TV series and the animation business in general. However, you may want to read this commentary on the current state of their business by someone who wasn't a victim of their incompetence.

Tuesday, July 24, 2007

Sunday, July 22, 2007

Two Ratatouille Links

My review of the book The Art of Ratatouille is up at the fps site. The short review: buy the book. Also on the site is something I should leave as a surprise. Check this out and make sure to click on the picture when you get there.

Friday, July 20, 2007

Ratatouille: Food for Thought

Now that Brad Bird has directed three feature films, certain themes are becoming apparent. The first is that society persecutes the talented. Perhaps the Iron Giant shouldn't be thought of as talented so much as alien, but certainly The Incredibles and Remy are talented and all three films feature persecution.

The characters struggle to overcome the persecution, but not because of the persecution itself but because the persecution stands in the way of them exercising their talents. Bird appears to feel that talent should rise to the top and that others should willingly defer to talent. This is where the charge of elitism, and even fascism, are leveled at Bird. What he never shows is how talent has to be developed and refined. The Iron Giant is built with all his capabilities. The Incredibles are presumably born with super powers. Remy is born with a genius nose.

Contrast this with Joe Johnston's film October Sky, based on Homer Hickam's book Rocket Boys. It's about a group of boys in a mining town who are inspired by Sputnik to take up rocketry. The standard path in the town is for boys to graduate high school and enter the mines, so the boys stand out for wanting something different from the social norm. While the town attempts to discourage their efforts, especially when it appears that one of their rockets caused a fire, the film also deals with the boys struggling to figure out rocketry and documents their early failures. As talented as these boys might be, it takes effort to develop their talents.

As an artist, Bird has to know this. There's no way that his first work was as good as what he's doing now. For whatever reason, though, the maturation of talent doesn't interest him. The abilities of Iron Giant, The Incredibles and Remy are fully formed.

For Bird, ambition is not for personal glory, it's simply to reach a position where talent can be exercised. This is an interesting contrast to John Lasseter's characters in Toy Story and Cars. In those films, Woody and Lightning McQueen attempt to lead out of ego and only discover happiness when they forsake ambition. Both directors deal with ambition, but it signifies completely different types of characters.

In Lasseter's world, ambition always pits a character against a rival. Success can only come by overcoming a competitor. For Bird, the talented are either all in agreement (like the supers in The Incredibles), or unique like Remy or the Iron Giant. What would happen in Bird's world if two equally talented protagonists attempted to express their talents towards competing ends?

By avoiding the struggle to develop a character's talents or having a character compete against equally talented opponents, Bird slants his films heavily towards his chosen characters. In much the way the Disney princesses are fated to ascend to their rightful places, Bird's characters also triumph. While the princesses live in fantasy worlds, Bird's live in ours, but his films are just as much fairy tales as the Disney films. Bird's characters don't compromise and aren't diminished by a hostile environment. Their talents are fully exercised and they accomplish everything they're capable of. And if that isn't a fantasy, I don't know what is.

The characters struggle to overcome the persecution, but not because of the persecution itself but because the persecution stands in the way of them exercising their talents. Bird appears to feel that talent should rise to the top and that others should willingly defer to talent. This is where the charge of elitism, and even fascism, are leveled at Bird. What he never shows is how talent has to be developed and refined. The Iron Giant is built with all his capabilities. The Incredibles are presumably born with super powers. Remy is born with a genius nose.

Contrast this with Joe Johnston's film October Sky, based on Homer Hickam's book Rocket Boys. It's about a group of boys in a mining town who are inspired by Sputnik to take up rocketry. The standard path in the town is for boys to graduate high school and enter the mines, so the boys stand out for wanting something different from the social norm. While the town attempts to discourage their efforts, especially when it appears that one of their rockets caused a fire, the film also deals with the boys struggling to figure out rocketry and documents their early failures. As talented as these boys might be, it takes effort to develop their talents.

As an artist, Bird has to know this. There's no way that his first work was as good as what he's doing now. For whatever reason, though, the maturation of talent doesn't interest him. The abilities of Iron Giant, The Incredibles and Remy are fully formed.

For Bird, ambition is not for personal glory, it's simply to reach a position where talent can be exercised. This is an interesting contrast to John Lasseter's characters in Toy Story and Cars. In those films, Woody and Lightning McQueen attempt to lead out of ego and only discover happiness when they forsake ambition. Both directors deal with ambition, but it signifies completely different types of characters.

In Lasseter's world, ambition always pits a character against a rival. Success can only come by overcoming a competitor. For Bird, the talented are either all in agreement (like the supers in The Incredibles), or unique like Remy or the Iron Giant. What would happen in Bird's world if two equally talented protagonists attempted to express their talents towards competing ends?

By avoiding the struggle to develop a character's talents or having a character compete against equally talented opponents, Bird slants his films heavily towards his chosen characters. In much the way the Disney princesses are fated to ascend to their rightful places, Bird's characters also triumph. While the princesses live in fantasy worlds, Bird's live in ours, but his films are just as much fairy tales as the Disney films. Bird's characters don't compromise and aren't diminished by a hostile environment. Their talents are fully exercised and they accomplish everything they're capable of. And if that isn't a fantasy, I don't know what is.

Tuesday, July 17, 2007

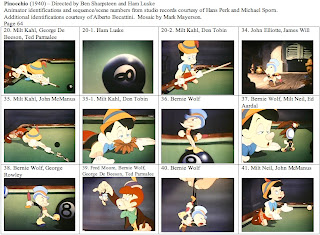

Pinocchio Part 17A

This is a great section for acting. The characters are very well defined and the conflict stems from their differing points of view. Lampwick is a delinquent, but one with an easy machismo. You can see why Pinocchio is attracted to him as a role model. Lampwick is also totally dismissive of Jiminy, and why shouldn't he be? Why would anyone take advice from an insect?

Frankie Darro never amounted to much in live action. He got stuck in a lot of B movies, though he did get the occasional role in more important films like William Wellman's Wild Boys of the Road. However, his performance as Lampwick is just perfect. The gruff edge in his voice and the dead-end kid attitude really make the character.

Fred Moore's animation, as I mentioned earlier, strikes a balance between portraying Lampwick as the tough that he is while still making him appealing. Bits of business like shot 15, where he grabs the cigar from the air after launching it with his billiards shot, show his gutter style. You can tell how much Moore is enjoying himself with this character and while Moore is known for lots of animation, I wonder if this wasn't his most successful performance.

Below are some frame grabs from shot 16 by Milt Kahl.

When I see animation like this, I feel badly that Kahl was stuck on such boring characters in the Disney features in the 1950s. He had a real talent for broad comedy and wasn't afraid to drastically change a character's shape. You can see more of this type of Kahl's animation in Saludos Amigos, where he handled the llama in the Donald Duck sequence. I'm also pretty sure he did the girl in Duck Pimples.

When I see animation like this, I feel badly that Kahl was stuck on such boring characters in the Disney features in the 1950s. He had a real talent for broad comedy and wasn't afraid to drastically change a character's shape. You can see more of this type of Kahl's animation in Saludos Amigos, where he handled the llama in the Donald Duck sequence. I'm also pretty sure he did the girl in Duck Pimples.

In a way, Kahl was a victim of his own drawing skill. He got stuck with the characters nobody else was good enough to draw, but look what he was capable of when a shot called for cartoon acting. I'd gladly give up his animation of Peter Pan and Prince Philip for more animation like the above.

Kahl's Pinocchio is a failure as a guttersnipe, but you've got to give him credit for trying.

The Jiminy unit does excellent work here. John Elliotte, Don Towsley and Bernie Wolf are all underrated animators based on their work in this film. Wolf does lovely work in the first part of Jiminy's tirade against Pinocchio. Very strong poses with emphatic lines of action. Ward Kimball finishes up with Jiminy leaving in disgust, easily matching Wolf's work.

Jiminy is upset seeing Pinocchio's moral lapses, but his anger is directed at Lampwick, who belittles him. That's what causes Jiminy to walk off; not Pinocchio's behaviour. When Jiminy returns for Pinocchio, it will be believable due to how this scene was written.

The image at left is from shot 58 by Kimball. This specific image is held for 4 frames. I always thought that it was odd. I have to wonder if it was originally shot on ones like the preceding footage but it went by too fast. I also wonder if Kimball shot a pose test and when the inbetweens were done, the fall didn't have the same punch. This is a case (and a rare one in Disney features) where the drawing calls attention to itself as a drawing. It does go by quickly, but you can feel that something odd happened. The effect is even more pronounced on a theatre screen. It does show that the studio was willing to violate its own aesthetic if the result was the right effect.

The image at left is from shot 58 by Kimball. This specific image is held for 4 frames. I always thought that it was odd. I have to wonder if it was originally shot on ones like the preceding footage but it went by too fast. I also wonder if Kimball shot a pose test and when the inbetweens were done, the fall didn't have the same punch. This is a case (and a rare one in Disney features) where the drawing calls attention to itself as a drawing. It does go by quickly, but you can feel that something odd happened. The effect is even more pronounced on a theatre screen. It does show that the studio was willing to violate its own aesthetic if the result was the right effect.

Frankie Darro never amounted to much in live action. He got stuck in a lot of B movies, though he did get the occasional role in more important films like William Wellman's Wild Boys of the Road. However, his performance as Lampwick is just perfect. The gruff edge in his voice and the dead-end kid attitude really make the character.

Fred Moore's animation, as I mentioned earlier, strikes a balance between portraying Lampwick as the tough that he is while still making him appealing. Bits of business like shot 15, where he grabs the cigar from the air after launching it with his billiards shot, show his gutter style. You can tell how much Moore is enjoying himself with this character and while Moore is known for lots of animation, I wonder if this wasn't his most successful performance.

Below are some frame grabs from shot 16 by Milt Kahl.

When I see animation like this, I feel badly that Kahl was stuck on such boring characters in the Disney features in the 1950s. He had a real talent for broad comedy and wasn't afraid to drastically change a character's shape. You can see more of this type of Kahl's animation in Saludos Amigos, where he handled the llama in the Donald Duck sequence. I'm also pretty sure he did the girl in Duck Pimples.

When I see animation like this, I feel badly that Kahl was stuck on such boring characters in the Disney features in the 1950s. He had a real talent for broad comedy and wasn't afraid to drastically change a character's shape. You can see more of this type of Kahl's animation in Saludos Amigos, where he handled the llama in the Donald Duck sequence. I'm also pretty sure he did the girl in Duck Pimples. In a way, Kahl was a victim of his own drawing skill. He got stuck with the characters nobody else was good enough to draw, but look what he was capable of when a shot called for cartoon acting. I'd gladly give up his animation of Peter Pan and Prince Philip for more animation like the above.

Kahl's Pinocchio is a failure as a guttersnipe, but you've got to give him credit for trying.

The Jiminy unit does excellent work here. John Elliotte, Don Towsley and Bernie Wolf are all underrated animators based on their work in this film. Wolf does lovely work in the first part of Jiminy's tirade against Pinocchio. Very strong poses with emphatic lines of action. Ward Kimball finishes up with Jiminy leaving in disgust, easily matching Wolf's work.

Jiminy is upset seeing Pinocchio's moral lapses, but his anger is directed at Lampwick, who belittles him. That's what causes Jiminy to walk off; not Pinocchio's behaviour. When Jiminy returns for Pinocchio, it will be believable due to how this scene was written.

The image at left is from shot 58 by Kimball. This specific image is held for 4 frames. I always thought that it was odd. I have to wonder if it was originally shot on ones like the preceding footage but it went by too fast. I also wonder if Kimball shot a pose test and when the inbetweens were done, the fall didn't have the same punch. This is a case (and a rare one in Disney features) where the drawing calls attention to itself as a drawing. It does go by quickly, but you can feel that something odd happened. The effect is even more pronounced on a theatre screen. It does show that the studio was willing to violate its own aesthetic if the result was the right effect.

The image at left is from shot 58 by Kimball. This specific image is held for 4 frames. I always thought that it was odd. I have to wonder if it was originally shot on ones like the preceding footage but it went by too fast. I also wonder if Kimball shot a pose test and when the inbetweens were done, the fall didn't have the same punch. This is a case (and a rare one in Disney features) where the drawing calls attention to itself as a drawing. It does go by quickly, but you can feel that something odd happened. The effect is even more pronounced on a theatre screen. It does show that the studio was willing to violate its own aesthetic if the result was the right effect.

Saturday, July 14, 2007

Thursday, July 12, 2007

The War Against Creatives

Here's the lead paragraph from a New York Times story called "Hollywood Executives Call For An End to Residual Payments."

If the producers get their way, creatives will benefit financially just once from their work while the conglomerates continue to collect profits for 100 years (the current length of corporate copyright) on exactly the same work.

(Animation artists do not qualify for individual residuals, though the members of The Animation Guild benefit from residual payments made to the union. Non-union animation artists are essentially in the position that the producers want to impose on writers, directors and actors.)

The case for owning your own work (or as much of it as possible) keeps getting stronger.

ENCINO, Calif., July 11 — In an unusually blunt session here today, several of Hollywood’s highest-ranking executives called for the end of the entertainment industry’s decades-old system of paying what are called residuals to writers, actors and directors for the re-use of movie and television programs after their initial showings.There are major negotiations coming up between Hollywood producers and the WGA and SAG, which represent writers and actors respectively. This may simply be a negotiating tactic, but there's the chance of major strikes next year as the guilds are interested in extending residuals into the new forms of media such as cell phones and the web and producers will resist it.

If the producers get their way, creatives will benefit financially just once from their work while the conglomerates continue to collect profits for 100 years (the current length of corporate copyright) on exactly the same work.

(Animation artists do not qualify for individual residuals, though the members of The Animation Guild benefit from residual payments made to the union. Non-union animation artists are essentially in the position that the producers want to impose on writers, directors and actors.)

The case for owning your own work (or as much of it as possible) keeps getting stronger.

Wednesday, July 11, 2007

Pinocchio Part 16A

Given the later existence of Disneyland, this has to be one of the most ironic sequences in Disney. Pleasure Island has many of the features of the standard amusement park, such as a ferris wheel, merry-go-round and roller coaster, but of course it has other attractions such as the Rough House, the Model Home Open for Destruction and Tobacco Road. The film implies that there's a thin line between fun and delinquency, which may be why Disneyland management works so hard to control the visitors. Anarchy lurks just below the surface.

Lampwick strikes a match on the Mona Lisa and then throws a brick through a stained glass window. Pinocchio chops up a piano, in effect fulfilling Stromboli's threat of reducing a woodcarver's work to firewood! The Disney artists are exhibiting a form of elitism here. The worst things aren't how people treat each other, it's how they treat creative work.

Fred Moore's work in shot 2 communicates beautifully. Lampwick discards most of a chicken when something catches his attention. Pinocchio, impressionable as ever, goes along with Lampwick's desire to get into a scrap. He pitches his pie and ice cream and then the two of them strut into the tent. That strut is just amazing for the amount of attitude that Moore gets into it. Their chests and rears are stuck out, their elbows are rigid while their arms swing and they walk to the beat of the jazzy soundtrack. The two of them are all arrogant appetite with no thought for anyone other than themselves.

Don Towsley's Jiminy in shot 4 does a great job of showing how vulnerable Jiminy is. Surrounded by stampeding feet, he has to duck and weave to avoid being squashed. It would be easy for Jiminy to give up at this point, so it's a measure of his resolve that this time, he doesn't abandon Pinocchio.

We've seen the coachman use his whip on donkeys but now we see him use it on two-legged creatures. Those faceless figures who shut the door to the Island are some of the scariest things ever in a Disney film. Are they wearing hoods or are they monsters of some sort? We don't know and never find out a thing about them. It's part of the power of this film that there are scary things that we only get glimpses of. The implication is that the world is more evil than we know and if we're not careful we'll be sucked into horrors beyond our imagination, as Pinocchio is about to find out.

Lampwick strikes a match on the Mona Lisa and then throws a brick through a stained glass window. Pinocchio chops up a piano, in effect fulfilling Stromboli's threat of reducing a woodcarver's work to firewood! The Disney artists are exhibiting a form of elitism here. The worst things aren't how people treat each other, it's how they treat creative work.

Fred Moore's work in shot 2 communicates beautifully. Lampwick discards most of a chicken when something catches his attention. Pinocchio, impressionable as ever, goes along with Lampwick's desire to get into a scrap. He pitches his pie and ice cream and then the two of them strut into the tent. That strut is just amazing for the amount of attitude that Moore gets into it. Their chests and rears are stuck out, their elbows are rigid while their arms swing and they walk to the beat of the jazzy soundtrack. The two of them are all arrogant appetite with no thought for anyone other than themselves.

Don Towsley's Jiminy in shot 4 does a great job of showing how vulnerable Jiminy is. Surrounded by stampeding feet, he has to duck and weave to avoid being squashed. It would be easy for Jiminy to give up at this point, so it's a measure of his resolve that this time, he doesn't abandon Pinocchio.

We've seen the coachman use his whip on donkeys but now we see him use it on two-legged creatures. Those faceless figures who shut the door to the Island are some of the scariest things ever in a Disney film. Are they wearing hoods or are they monsters of some sort? We don't know and never find out a thing about them. It's part of the power of this film that there are scary things that we only get glimpses of. The implication is that the world is more evil than we know and if we're not careful we'll be sucked into horrors beyond our imagination, as Pinocchio is about to find out.

Sunday, July 08, 2007

The Animated Man

Biographies of Walt Disney tend to fall into two camps. There are the hagiographies that tend to deal with Disney's life in mythological terms. They cover the adverse conditions that Disney triumphed over: the cruel father, the harsh childhood, the early bankruptcy, the disloyal staff, the film industry predators, and the skeptics. With Disney's creation of Steamboat Willie, Flowers and Trees, The Three Little Pigs, Snow White, the various TV series and Disneyland, we have a figure whose determination and faith in his abilities triumph over the naysayers to allow him to delight audiences everywhere. These books imply that the projects unfinished at Disney's death, such as EPCOT, would have continued Disney's string of triumphs. Had Disney lived longer, who knows what wonders he would have brought forth?

Biographies of Walt Disney tend to fall into two camps. There are the hagiographies that tend to deal with Disney's life in mythological terms. They cover the adverse conditions that Disney triumphed over: the cruel father, the harsh childhood, the early bankruptcy, the disloyal staff, the film industry predators, and the skeptics. With Disney's creation of Steamboat Willie, Flowers and Trees, The Three Little Pigs, Snow White, the various TV series and Disneyland, we have a figure whose determination and faith in his abilities triumph over the naysayers to allow him to delight audiences everywhere. These books imply that the projects unfinished at Disney's death, such as EPCOT, would have continued Disney's string of triumphs. Had Disney lived longer, who knows what wonders he would have brought forth?The other camp attacks Disney for his taste (Richard Schickel's The Disney Version) or his character (Marc Elliot's Walt Disney: Hollywood's Dark Prince; the recent play Disney in Deutschland by John J. Powers). These authors are intent on showing Disney's feet of clay; we wouldn't admire him if we only knew the truth.

Michael Barrier's The Animated Man: A Life of Walt Disney falls into neither camp and is all the better for it. While we know Barrier for his work as an animation historian, he earned a living for many years writing about business and entrepreneurs. The is the lens that he views Disney through. While the facts of Disney's life are generally well-known (though details are still being filled in), it's the interpretation of that life where Barrier makes his major contribution.

Disney's father Elias is often portrayed as a Dickensian villain, but Barrier points out the similarities between Elias's entrepreneurial bent and Disney's own. Neither was content to stick to just one thing and both continuously chased success.

Barrier notes how even into the early 1930s, Disney's drive to dominate the animation business was based more on competitiveness than any artistic vision. Disney only gradually awakened to the acting possibilities of the animation medium and unfortunately they only held his attention for a relatively short time. For Barrier, Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs is Disney's high point, but it's clear in Barrier's view that Disney didn't fully realize what he had accomplished or how to proceed beyond Snow White. While Disney poured money into the other pre-war features to make them more visually elaborate, with few exceptions the acting didn't match the emotional impact of his first feature.

Disney's entrepreneurial qualities may have worked against his artistic sensibilities in the long term. Entrepreneurs identify completely with their companies and immerse themselves in the minute details of running their businesses. Often, this means that their companies can't grow beyond a certain size as they become too big to be managed by a single person. Disney defied gravity in this regard, but he spread himself thinner and thinner over time and the quality of his company's product suffered as a result. His loss of interest in animation in the '50s meant that the films remained slick but were full of mis-steps and inconsistencies. His expansion into live action films and TV rarely resulted in anything, nostalgia aside, that's stood the test of time.

In the 1930s, the artists were pushing against the limitations of animation and that stimulated Disney into thinking in new ways. By the 1950s, Disney was no longer willing to have anyone push against him. This is why he hired impersonal directors and lacklustre performers, none of whom had clout to challenge Disney's decisions. As a result, nothing was better than an overstretched Disney was capable of creating himself. Furthermore, Barrier makes it clear that TV dominated Disney rather than the reverse.

Barrier rightly identifies the passiveness of Pinocchio's character and documents how Disney accidentally found a star presence in Fess Parker and then did little to build him up. This made me realize that I couldn't name a strong male lead in any Disney feature, live or animated. For whatever reason, Disney was uncomfortable with Hollywood's idea of heroism and didn't feature it. For all of Disney's own accomplishments, he saw the world in non-heroic terms. People are always on the defensive and triumph more through perseverance than by dominating their environments. Fess Parker might have developed into another John Wayne, but Disney had no use for Wayne's kind of character or story.

Michael Barrier has stripped away the mythology and examined Disney in very down to earth terms. His Disney is always an entrepreneur and only occasionally an artist. Where others only see Disney successes, Barrier sees mediocre live films and TV, tying them to the same personal qualities that fueled Disney's better films. While Barrier is critical, he never resorts to character assassination.

You may not agree with all of this book's judgments, but this Disney biography cuts away much of the fluff and the misconceptions that have attached themselves to Disney and presents you with a believable human being, one whose work is a logical outgrowth of his life and personality. That alone makes this book worth reading.

Thursday, July 05, 2007

Which Way Do We Go, George? Which Way Do We Go?

Keith Lango comments on the conclusion to my MRP and Peter Hon adds some very good thoughts about the time and effort it takes to do an independent film.

I know exactly what he's talking about. I've been debating whether to start a graphic novel, where I could tell a lengthy story, or do a short animated film. I'm guessing that they'd take me the same amount of time, but one would allow for a more complex story. However, I wonder if I'm not thinking boldly enough.

I think that trying to make a short film that's as polished as professional work is a mistake. Adding up the man hours (more like man years) that are spent on any studio production (TV or film), it's almost impossible for an individual to invest the same amount of time. To make a Pixar quality short as an individual, you might have to start immediately after the doctor slaps your behind in the delivery room and you might not finish before landing in your death bed.

So the thing to do is focus on content. That's where so much of studio animation falls short anyway. Studio content is aimed at the widest possible audience and the audience goes for it because it's similar to what's been done before.

Say something new (or say something familiar in a new way) and forget about slickness. If what you're saying isn't worth paying attention to, slickness won't change that. Furthermore, how many ideas are worth spending years of your life on? If you've got one, I sincerely congratulate you. However, an awful lot of animated films aren't worth the time spent to watch them, let alone to make them. Rather than worrying about refining our work, maybe we should worry about saying something interesting.

I'm not attacking the idea of craft, but I've never felt that craft was enough. Just as many animation artists publish sketchbooks, maybe we need an animated equivalent. Whether drawn, stop motion or cgi, maybe we need to work for more spontaneity and less for refinement. Elevate content over form. Forget about sanding off the rough edges. Make your statement quickly and move on.

I know exactly what he's talking about. I've been debating whether to start a graphic novel, where I could tell a lengthy story, or do a short animated film. I'm guessing that they'd take me the same amount of time, but one would allow for a more complex story. However, I wonder if I'm not thinking boldly enough.

I think that trying to make a short film that's as polished as professional work is a mistake. Adding up the man hours (more like man years) that are spent on any studio production (TV or film), it's almost impossible for an individual to invest the same amount of time. To make a Pixar quality short as an individual, you might have to start immediately after the doctor slaps your behind in the delivery room and you might not finish before landing in your death bed.

So the thing to do is focus on content. That's where so much of studio animation falls short anyway. Studio content is aimed at the widest possible audience and the audience goes for it because it's similar to what's been done before.

Say something new (or say something familiar in a new way) and forget about slickness. If what you're saying isn't worth paying attention to, slickness won't change that. Furthermore, how many ideas are worth spending years of your life on? If you've got one, I sincerely congratulate you. However, an awful lot of animated films aren't worth the time spent to watch them, let alone to make them. Rather than worrying about refining our work, maybe we should worry about saying something interesting.

I'm not attacking the idea of craft, but I've never felt that craft was enough. Just as many animation artists publish sketchbooks, maybe we need an animated equivalent. Whether drawn, stop motion or cgi, maybe we need to work for more spontaneity and less for refinement. Elevate content over form. Forget about sanding off the rough edges. Make your statement quickly and move on.

Pinocchio Part 15A

This sequence introduces Lampwick, sort of the anti-Jiminy. His anticipation of the fun on Pleasure Island, contrasted to the Coachman's reaction shot (9.1) sets up the two sides of the island that we'll get to see.

While you couldn't know it until seeing the film a second time, the coach is drawn by donkeys, undoubtedly ones who were previously passengers.

Once again, Pinocchio is a blank slate, not recognizing that the ace of spades isn't a ticket, though it generally is a symbol of death. Lampwick's personality overpowers Pinocchio, not letting him finish a sentence. Lampwick indulges himself by shooting rocks at the donkeys. For all of his bravado, he proves to be as gullible as Pinocchio about what awaits them. If he only knew where those donkeys came from...

Fred Moore is the star here. In just a few shots, he defines Lampwick as a type: the boy who thinks he's tough and who can't wait to grow up to be a "hoodlum" as Jiminy will call him. The appealing design is necessary. We've got to like Lampwick enough so that when his transformation occurs, it horrifies us. If he is a unlikable character, we might cheer his punishment, so Moore has to walk the line between attracting and repelling us with the character and he strikes the right balance.

Note shots 3 and 9 for the coach passengers. They are simplified, probably due to the size they were drawn. This problem plagues the Fleischer version of Gulliver's Travels quite a bit during the sequence where Gulliver is bound by the Lilliputians. It's a bit surprising to see it in this film, even for only a few shots.

There are some nice effects shots as the coach reaches the shore, the boys board the ship and the ship sails to the island. Shot 18 uses a held painting of the boat and water effects that are panned towards the opening in the rocks. The shot is simple compared to much in the film, but it shows how good art direction and a strong composition can often do a better job than elaborate effects.

Addendum to Part 13A: There's been discussion about Shamus Culhane's animation of Honest John and whether or not he was unfairly deprived of credit. I have no more information on that, but on page 145 of The Animated Man: A Life of Walt Disney by Michael Barrier, Hugh Fraser is quoted as to how he did 48 pencil tests of sequence 7, shot 30. Culhane claimed to have worked on sequence 7, where Honest John and Gideon plot with the coachman, and while Fraser's scene was probably an extreme case, it's possible that Culhane's scenes were also revised numerous times after he left by Norm Tate, leaving little or nothing of Culhane's work. T. Hee was the sequence director of sequences 3 and 7, both of which Culhane claimed to have worked on, so Hee may be more responsible than Walt Disney for Culhane not getting credit in the drafts or on the film.

While you couldn't know it until seeing the film a second time, the coach is drawn by donkeys, undoubtedly ones who were previously passengers.

Once again, Pinocchio is a blank slate, not recognizing that the ace of spades isn't a ticket, though it generally is a symbol of death. Lampwick's personality overpowers Pinocchio, not letting him finish a sentence. Lampwick indulges himself by shooting rocks at the donkeys. For all of his bravado, he proves to be as gullible as Pinocchio about what awaits them. If he only knew where those donkeys came from...

Fred Moore is the star here. In just a few shots, he defines Lampwick as a type: the boy who thinks he's tough and who can't wait to grow up to be a "hoodlum" as Jiminy will call him. The appealing design is necessary. We've got to like Lampwick enough so that when his transformation occurs, it horrifies us. If he is a unlikable character, we might cheer his punishment, so Moore has to walk the line between attracting and repelling us with the character and he strikes the right balance.

Note shots 3 and 9 for the coach passengers. They are simplified, probably due to the size they were drawn. This problem plagues the Fleischer version of Gulliver's Travels quite a bit during the sequence where Gulliver is bound by the Lilliputians. It's a bit surprising to see it in this film, even for only a few shots.

There are some nice effects shots as the coach reaches the shore, the boys board the ship and the ship sails to the island. Shot 18 uses a held painting of the boat and water effects that are panned towards the opening in the rocks. The shot is simple compared to much in the film, but it shows how good art direction and a strong composition can often do a better job than elaborate effects.

Addendum to Part 13A: There's been discussion about Shamus Culhane's animation of Honest John and whether or not he was unfairly deprived of credit. I have no more information on that, but on page 145 of The Animated Man: A Life of Walt Disney by Michael Barrier, Hugh Fraser is quoted as to how he did 48 pencil tests of sequence 7, shot 30. Culhane claimed to have worked on sequence 7, where Honest John and Gideon plot with the coachman, and while Fraser's scene was probably an extreme case, it's possible that Culhane's scenes were also revised numerous times after he left by Norm Tate, leaving little or nothing of Culhane's work. T. Hee was the sequence director of sequences 3 and 7, both of which Culhane claimed to have worked on, so Hee may be more responsible than Walt Disney for Culhane not getting credit in the drafts or on the film.

Tuesday, July 03, 2007

Six Authors in Search of a Character: Part 14, Conclusion

Animators had more control of their characters’ behaviour and fewer collaborators in the silent era than at any time since, but they didn’t know what to do with that control. Their backgrounds as cartoonists did not provide them with direct contact with an audience, so their understanding of an audience’s expectations was limited. They also had no experience fashioning characters in narratives longer than a comic strip. The struggle to develop animation technology at the same time they were turning out large amounts of animation overshadowed any thought about one animator controlling a single character. Animators’ physical isolation in New York from the mainstream film business in California and their lack of affiliation with live action studios during the silent era insulated them in a ghetto-like situation where they developed at their own provincial pace.

Disney altered the landscape significantly but didn’t change it in fundamental ways. The assembly line that had been developed in the silent era was not thrown away, only modified. The result was a double-edged sword for animators. The newer system freed animators from the concerns of doing finished-quality drawings and provided them with enough assistance so they could concentrate on communicating a character’s thoughts and emotions to the audience. However, their control of timing was taken by directors, their control of style was taken by character designers, and their control of emotion was taken by voice actors. Control of a great deal of a character’s physical behaviour migrated upstream to the story artists.

In the TV era, the same structure remained in place though the need to output animation grew exponentially. These conditions defeated the best aspects of the Disney system but allowed the worst aspects to survive. Animators had no more control than they had on theatrical shorts or features while the need for productivity prevented them from the level of refinement the system formerly allowed.

With motion capture becoming increasingly common as an effect in live action films and with the creation of films that appear to be animated but are motion-captured imitations, the importance of the animator is further reduced. Live action directors don’t understand the animation process and are not shy about praising actors at the expense of animators. Here’s Gore Verbinski, director of Pirates of the Caribbean: Dead Man’s Chest reflecting on Bill Nighy’s motion-captured performance of Davy Jones.

Actor Andy Serkis has experienced how it feels to create a motion-captured performance and interact with animator collaborators.

Animators, due to the assembly line nature of production, are always forced to rely on somebody else’s string while they supply the pearls. This is my crux of disagreement with Michael Barrier. He feels that casting animators by character allows for more unified behaviour; animators supplying their own string as it were.

Here is animator Tony White on the centrality of the voice track to animated behaviour.

While some animators under certain conditions may approach the kind of actor-character identification that is possible with live acting, those cases are rare due to the realities of the animation industry. Barrier feels that this identification is what animation should aspire to. I agree with him, but I don’t think that casting by character is sufficient to achieve it. There are too many other variables.

Story artist Bill Peet felt that he was the prime contributor to One Hundred and One Dalmatians and that others simply enhanced his contributions.

In researching and writing this MRP, I am left with the question of whether casting by character makes a significant difference, given how collaborative the creation of an animated character’s behaviour is. In the case of a single animator per character, the pre-production work gets passed through that animator’s sensibility; in that sense the animator may function more as a synthesizer than as a creator, though the animator unquestionably makes a contribution. While within the industry animators are routinely compared to actors, perhaps a better analogy is to musicians in a symphony orchestra. Such musicians are responsible for playing the notes on the page while filtering them through the interpretation of the conductor. Within the ensemble, how much room is there for musicians to assert themselves?

While casting animators by scene or sequence might dilute a character’s behaviour due to too many authors, it might also salvage a character’s behaviour by averaging out the ability of the contributing animators. Casting an animator with a talent for comedy on certain scenes and for pathos on others might allow those scenes to work where a single animator might not be versatile enough to meet the challenges required of a character.

Casting by character has been used in the recent past at Disney, resulting in films that have proven popular and received critical approval. The Little Mermaid, Beauty and the Beast, Aladdin and The Lion King were all cast by character. By contrast, Pixar has always cast by scene. Toy Story, Finding Nemo and The Incredibles have earned the same box office success and critical kudos as the aforementioned Disney films.

Is one form of casting inherently superior? The industry has clearly not settled on one approach. Audiences and mainstream critics seem unaware of the difference. The existence of supervising animators may render the debate moot, as there has never been a feature where each character was animated by a single artist.

In live action terms, we can point to films that are dominated by producers, by directors, by writers and by performers. There is nothing inherently superior about one more than another; the quality of a film doesn’t rest on who dominates but on whether the film’s elements cohere into a satisfying whole. The elements that make up an animated film differ from live action, but they must also cohere if a film is to be successful.

If the creation of animated behaviour is characterized more by synthesizing than by creating, does it matter if the synthesizer is the director, the voice actor or the animator? Each of them will be forced to incorporate contributions by people working on other parts of the process. Should the animator inherently be more privileged than other contributors?

If you believe that the animator should dominate -- that the animator should have the opportunity to bring a unique sensibility to a character -- then my conclusion is that the current production structure needs to be reworked, as its current incarnation intentionally removes control from animators for the sake of efficiency. The current approach attempts to create coherence in pre-production before the animators begin and then impose the coherence on them.

I don’t know what an animator-centric production would look like. At the very least, it would require the voice cast be assembled to rehearse together, with the director and animators present to shape their performances. Then the director and animators would work on staging, eliminating the storyboard artists and layout artists. Following this, the animators would bring their characters to life.

This is still more collaborative than live acting; each role would still be split between voice actor and animator. Unless a production was willing to use the animators’ voices, I can’t see a way of making animated characters less collaborative than this. It’s possible that this approach would be impractical from the standpoint of budget and schedule. It’s such a radical break with current procedures that it might take several films for the animators to adjust and before the results were worth watching.

The one animator in mainstream films who managed to maintain control of his characters and avoid the use of a voice track was Ray Harryhausen. In features, Harryhausen added stop-motion puppets to live action films, always working on fantastic creatures that live action couldn’t manage. He rose to the position of associate producer or producer on his films after 1963’s Jason and the Argonauts, certainly a rarity for an animator still doing frame by frame work on a film. Harryhausen’s only attempt at lip synch was a test for an unrealized project based on Baron Munchausen. “It was the first time that I experimented with animation and dialogue, and because of the time and effort, it was the last” (Harryhausen 286). Harryhausen’s characters may emit sounds, but never dialogue.

Harryhausen was inspired by the 1933 version of King Kong and later worked with Kong’s effects supervisor and animator Willis O’Brien on the film Mighty Joe Young. As Gary Giddins points out,

Harryhausen is one of a kind. He built a production structure to suit himself and it hasn’t been imitated by anyone for major productions. The only other area that approaches Harryhausen’s level of control is independent animation. It’s only on short projects that animators have the freedom to control a character without having to collaborate, but just as silent animators were limited by their backgrounds as cartoonists, many independent animators are limited by their backgrounds in fine arts. They prize the image over believable characters. Norman McLaren is an example of an independent animator who controlled his films but was more interested in design and the formal aspects of the animation process than he was in creating characters.

Those independent animators who are concerned with characters, such as Borge Ring (Anna and Bella), work alone or in small teams. As a result, their films are short and are produced infrequently. Prior to the creation of internet sites like iFilm and YouTube, the market for short films was small, so these film makers did not get much exposure outside of festivals. This limited their influence on the animation industry.

I don’t know if animator-centered films are possible from large studios. There is no incentive to destroy the production structure that’s proven profitable and functioned for nearly a century. When new technologies are introduced, it’s easier to adjust the production structure rather than replace it.

However, between the budget and schedule demands of TV, the geographical and cultural separation of animators from TV pre-production, and the rising use of motion capture in features, animators are being increasingly marginalized. Perhaps fashions will change as media and technology evolve or perhaps animation needs a manifesto similar to Dogme, challenging artists to work in different ways.

In any case, the structure of production has unquestionably forced animators into sharing control, with repercussions for both animated characters and criticism. I hope that this MRP has clarified the nature of the collaboration’s historical roots and how it functions in an industrial setting.

Disney altered the landscape significantly but didn’t change it in fundamental ways. The assembly line that had been developed in the silent era was not thrown away, only modified. The result was a double-edged sword for animators. The newer system freed animators from the concerns of doing finished-quality drawings and provided them with enough assistance so they could concentrate on communicating a character’s thoughts and emotions to the audience. However, their control of timing was taken by directors, their control of style was taken by character designers, and their control of emotion was taken by voice actors. Control of a great deal of a character’s physical behaviour migrated upstream to the story artists.

In the TV era, the same structure remained in place though the need to output animation grew exponentially. These conditions defeated the best aspects of the Disney system but allowed the worst aspects to survive. Animators had no more control than they had on theatrical shorts or features while the need for productivity prevented them from the level of refinement the system formerly allowed.

With motion capture becoming increasingly common as an effect in live action films and with the creation of films that appear to be animated but are motion-captured imitations, the importance of the animator is further reduced. Live action directors don’t understand the animation process and are not shy about praising actors at the expense of animators. Here’s Gore Verbinski, director of Pirates of the Caribbean: Dead Man’s Chest reflecting on Bill Nighy’s motion-captured performance of Davy Jones.

"There's a point in the process where things have to be singular, they have to be from one person's point of view. I think you get that from an actor's performance, and not with a committee of animators and animation directors and even from myself. It's just too much to go through to say, 'Let's create nuance from scratch.' You need somebody to start it. We're always going to need great acting" (Cohen 1).In these films, directors see animators purely as technicians; they are considered special effects artists not people capable of defining a character’s behaviour. In animation terms, the animator is used more like an assistant animator. Someone else has created the movement and the assistant animator’s job is to refine it into a satisfactory shape.

Actor Andy Serkis has experienced how it feels to create a motion-captured performance and interact with animator collaborators.

“Animators are actors in the sense that they draw from their own life experience and emotions and bring that to a character. They even use their own facial expressions to convey a feeling by acting into a mirror. However, if there are 40 animators working on individual segments of Gollum, the string that holds the pearls on the necklace, so to speak, could be missing, and given that the character has such a complex psychological and emotional journey, he could take on 40 different personalities! But here there was a very different agenda. Instead of looking into mirrors, the animators would be using the performance of a single actor, and sticking closely to the footage we had shot on location and in motion capture, and that would be the emotional string that would hold it together” (95).Serkis can be forgiven for not knowing that even in completely animated films, there must be that string. It’s usually supplied by the director, using the voice track, the timing, the storyboard and the character layouts. It may be supplied by a lead animator on a character. Glen Keane was the lead on the titular Aladdin character in the Disney feature.

“Animation is such a team effort no one man can take credit for a character. In the Aladdin unit, I have a great team of animators working with me doing vital acting moments in the film. The challenge is for all of us to think as one. The lead animator sets the pace for the character in the film. That’s why each of the animators in my unit checks with me. Besides [directors] Ron [Clements] and John [Musker], the lead animator is the only one who sees everybody’s work and knows if somebody’s heading off in this direction or that direction.Serkis and Keane hold roughly equivalent positions, though they use different techniques. Each of them collaborates with others in creating a character’s behaviour, setting the tone and editing the contributions of their collaborators. Serkis, by supplying his character’s voice, has an advantage over Keane.

“He becomes the conscience of that character throughout the film. If one of Aladdin’s personality traits are violated, I have to speak up in Aladdin’s behalf in the film, and raise my hand and say, ‘Hey, that’s not me, that’s not me – I wouldn’t do that’” (John Culhane 71-72).

Animators, due to the assembly line nature of production, are always forced to rely on somebody else’s string while they supply the pearls. This is my crux of disagreement with Michael Barrier. He feels that casting animators by character allows for more unified behaviour; animators supplying their own string as it were.

“Animation of the kind that Walt Disney had begun cultivating in the middle thirties – and that had flowered in Tytla’s scenes of the dwarfs – was powerful because its cartoon exaggeration could reveal so fully the emotional life of its characters. When an animator immersed himself in that emotional life, the bond between character and animator could be as strong as any bond between character and actor on the stage” (Hollywood 313).My point is that truly animator-centric characters cannot exist in the current production structure. Even if one animator contributes all of a character’s scenes, the pre-production decisions that are handed to the animator, most especially the voice track, make the character’s behaviour collaborative. Tytla may have been sympathetic to Grumpy’s voice track, performed by Pinto Colvig, but because the audience would hear Colvig’s reading, where it would be ignorant of storyboard and layout drawings supplied to Tytla, Tytla had no choice but to take Colvig’s reading into account in his animation.

Here is animator Tony White on the centrality of the voice track to animated behaviour.

“It is impossible to produce good and convincing dialogue [animation] without first listening intently to what has been recorded and getting under the skin of its meaning and impetus. On one level, it is just words. On another level, it is a succession of accents and pauses and breaths, and even emotion, that makes up every single line of dialogue. Only by listening intently and frequently will you begin to feel what is really being said in a delivery (not just the sound of the words), and then begin to get a sense of how the character looks, how the character needs to stand, how the character needs to emphasize the words they are saying. Only then, when you are actually under the skin of the dialogue, should you pick up a pencil and draw.” (249)The voice-body split that became the norm in animation at the start of the sound era was something new. It did not exist in theatre. Dubbing in live action film was certainly not the norm. It did not even exist in puppetry. It only existed in animation due to something close to an original sin: the decision in the silent era to divide a film by sequence instead of by character. Once the gulf between animator and character was opened, it continued to get wider. Disney attempted to close it by casting by character, but at the same time he did that he was pulling more control of the characters away from animators into pre-production for the sake of efficiency. To his credit, he didn’t do it for financial reasons; he did it to gain greater artistic control over the films he was producing.

While some animators under certain conditions may approach the kind of actor-character identification that is possible with live acting, those cases are rare due to the realities of the animation industry. Barrier feels that this identification is what animation should aspire to. I agree with him, but I don’t think that casting by character is sufficient to achieve it. There are too many other variables.

Story artist Bill Peet felt that he was the prime contributor to One Hundred and One Dalmatians and that others simply enhanced his contributions.

“The public probably thinks the animator sits down and starts doing it from scratch. I did storyboards, thousands of them, and character design; I would direct the voice recordings.The above not only exposes the tension over credit, it also shows that the artists themselves can’t agree on where control of a character lies. Peet wrote the script and did the storyboard for One Hundred and One Dalmatians, based on the book by Dodie Smith. Marc Davis, cast by character as Barrier would prefer, animated Cruella De Vil. Live action reference footage of actress Mary Wickes was shot for the role of Cruella (Frank Thomas 320). Betty Lou Gerson recorded Cruella’s voice track. Does this character represent any one contributor’s point of view? Can any of the above people claim the same level of control that an actor routinely has over a character?

“Then guys like Marc Davis, Ken Anderson, and Woolie Reitherman would take credit for my Cruella De Vil and all of the personalities. Those personalities were delineated in drawings, and believe me; I can draw them as well or better than any of them” (Province 163).

Helene Stanley (left) and Mary Wickes act out a scene as reference for Disney animators for One Hundred and One Dalmatians. From Disney Animation: The Illusion of Life by Frank Thomas and Ollie Johnston.

In researching and writing this MRP, I am left with the question of whether casting by character makes a significant difference, given how collaborative the creation of an animated character’s behaviour is. In the case of a single animator per character, the pre-production work gets passed through that animator’s sensibility; in that sense the animator may function more as a synthesizer than as a creator, though the animator unquestionably makes a contribution. While within the industry animators are routinely compared to actors, perhaps a better analogy is to musicians in a symphony orchestra. Such musicians are responsible for playing the notes on the page while filtering them through the interpretation of the conductor. Within the ensemble, how much room is there for musicians to assert themselves?

While casting animators by scene or sequence might dilute a character’s behaviour due to too many authors, it might also salvage a character’s behaviour by averaging out the ability of the contributing animators. Casting an animator with a talent for comedy on certain scenes and for pathos on others might allow those scenes to work where a single animator might not be versatile enough to meet the challenges required of a character.

Casting by character has been used in the recent past at Disney, resulting in films that have proven popular and received critical approval. The Little Mermaid, Beauty and the Beast, Aladdin and The Lion King were all cast by character. By contrast, Pixar has always cast by scene. Toy Story, Finding Nemo and The Incredibles have earned the same box office success and critical kudos as the aforementioned Disney films.

Is one form of casting inherently superior? The industry has clearly not settled on one approach. Audiences and mainstream critics seem unaware of the difference. The existence of supervising animators may render the debate moot, as there has never been a feature where each character was animated by a single artist.

In live action terms, we can point to films that are dominated by producers, by directors, by writers and by performers. There is nothing inherently superior about one more than another; the quality of a film doesn’t rest on who dominates but on whether the film’s elements cohere into a satisfying whole. The elements that make up an animated film differ from live action, but they must also cohere if a film is to be successful.

If the creation of animated behaviour is characterized more by synthesizing than by creating, does it matter if the synthesizer is the director, the voice actor or the animator? Each of them will be forced to incorporate contributions by people working on other parts of the process. Should the animator inherently be more privileged than other contributors?

If you believe that the animator should dominate -- that the animator should have the opportunity to bring a unique sensibility to a character -- then my conclusion is that the current production structure needs to be reworked, as its current incarnation intentionally removes control from animators for the sake of efficiency. The current approach attempts to create coherence in pre-production before the animators begin and then impose the coherence on them.

I don’t know what an animator-centric production would look like. At the very least, it would require the voice cast be assembled to rehearse together, with the director and animators present to shape their performances. Then the director and animators would work on staging, eliminating the storyboard artists and layout artists. Following this, the animators would bring their characters to life.

This is still more collaborative than live acting; each role would still be split between voice actor and animator. Unless a production was willing to use the animators’ voices, I can’t see a way of making animated characters less collaborative than this. It’s possible that this approach would be impractical from the standpoint of budget and schedule. It’s such a radical break with current procedures that it might take several films for the animators to adjust and before the results were worth watching.

The one animator in mainstream films who managed to maintain control of his characters and avoid the use of a voice track was Ray Harryhausen. In features, Harryhausen added stop-motion puppets to live action films, always working on fantastic creatures that live action couldn’t manage. He rose to the position of associate producer or producer on his films after 1963’s Jason and the Argonauts, certainly a rarity for an animator still doing frame by frame work on a film. Harryhausen’s only attempt at lip synch was a test for an unrealized project based on Baron Munchausen. “It was the first time that I experimented with animation and dialogue, and because of the time and effort, it was the last” (Harryhausen 286). Harryhausen’s characters may emit sounds, but never dialogue.

Harryhausen was inspired by the 1933 version of King Kong and later worked with Kong’s effects supervisor and animator Willis O’Brien on the film Mighty Joe Young. As Gary Giddins points out,

“Harryhausen shunned sentimentality after that – no easy feat as he was forced to tailor most of his work to children. Indeed, for all his devotion to Kong, he never animated creatures that were quite as sympathetic or anthropomorphic (beyond his penchant for manly musculature) as Kong” (125-26).This raises an issue that so far has been ignored. While I admire Harryhausen’s imagination and craft, I prefer the behaviour of O’Brien’s creatures. If a film is structured so that it is cast by character, we are left with the ability of a specific animator when judging what’s on screen. Bad casting and acting are common in live action films and in theatre. There’s no reason why animation should escape similar problems.

Harryhausen is one of a kind. He built a production structure to suit himself and it hasn’t been imitated by anyone for major productions. The only other area that approaches Harryhausen’s level of control is independent animation. It’s only on short projects that animators have the freedom to control a character without having to collaborate, but just as silent animators were limited by their backgrounds as cartoonists, many independent animators are limited by their backgrounds in fine arts. They prize the image over believable characters. Norman McLaren is an example of an independent animator who controlled his films but was more interested in design and the formal aspects of the animation process than he was in creating characters.

Those independent animators who are concerned with characters, such as Borge Ring (Anna and Bella), work alone or in small teams. As a result, their films are short and are produced infrequently. Prior to the creation of internet sites like iFilm and YouTube, the market for short films was small, so these film makers did not get much exposure outside of festivals. This limited their influence on the animation industry.

I don’t know if animator-centered films are possible from large studios. There is no incentive to destroy the production structure that’s proven profitable and functioned for nearly a century. When new technologies are introduced, it’s easier to adjust the production structure rather than replace it.

However, between the budget and schedule demands of TV, the geographical and cultural separation of animators from TV pre-production, and the rising use of motion capture in features, animators are being increasingly marginalized. Perhaps fashions will change as media and technology evolve or perhaps animation needs a manifesto similar to Dogme, challenging artists to work in different ways.

In any case, the structure of production has unquestionably forced animators into sharing control, with repercussions for both animated characters and criticism. I hope that this MRP has clarified the nature of the collaboration’s historical roots and how it functions in an industrial setting.

Sunday, July 01, 2007

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)