Friday, December 31, 2010

Canadian Video Game Studios

Monday, December 27, 2010

A Bad Year at the Box Office

North American attendance for 2010 is expected to drop about 4 percent, to 1.28 billion, according to Hollywood.com, which compiles box-office statistics. Revenue is projected to fall less than 1 percent, to $10.5 billion. It has been propped up by a 5 percent increase in the average ticket price, to $7.85, thanks to 3-D.Last January, I posted this chart from Deadline Hollywood:

If the numbers are correct,the number of tickets sold is lower than it has been in any year since 1999. Revenue is down as well, even with the average cost of a ticket rising from $7.46 to $7.85.

This implies that the bloom is off the 3-D rose. There have been more 3-D films released this year, yet fewer people are willing to pay to see them. While this doesn't imply the impending death of 3-D, it does imply that 3-D's novelty has worn off. Its revival was just a blip, not a sea change; it will no longer increase box office revenue on its own.

It also shows that Hollywood has gone too far in raising ticket prices. While it is understandable that ticket sales should fall during a recession, they have fallen lower than the earlier years of this recession and lower than they've been in more than a decade. Time will tell if this is a trend or just an aberration, but it is something that Hollywood should worry about. A downward trend in attendance is the last thing the film industry needs.

Thursday, December 23, 2010

Dirty Tricks

The United States Department of Justice has found Pixar and Lucasfilm guilty of restraint of trade.

The United States Department of Justice has found Pixar and Lucasfilm guilty of restraint of trade."Beginning no later than January 2005, Lucasfilm and Pixar agreed to a three-part protocol that restricted recruiting of each other's employees. First, Lucasfilm and Pixar agreed they would not cold call each other's employees. Cold calling involves communicating directly in any manner (including orally, in writing, telephonically, or electronically) with another firm's employee who has not otherwise applied for a job opening. Second, they agreed to notify each other when making an offer to an employee of the other firm. Third, they agreed that, when offering a position to the other company's employee, neither would counteroffer above the initial offer.At the same time that Pixar was making Toy Story 3, where the villain hid behind an agreeable facade in order to manipulate others for his own selfish ends, the company was doing the identical thing to its employees. If you have a taste for wading through legal jargon, you can read the official documents here.

...

"Lucasfilm's and Pixar's agreed-upon protocol disrupted the competitive market forces for employee talent. It eliminated a significant form of competition to attract digital animation employees and other employees covered by the agreement. Overall, it substantially diminished competition to the detriment of the affected employees who likely were deprived of information and access to better job opportunities.

"The agreement was a naked restraint of trade that was per se unlawful under Section 1 of the Sherman Act, 15 U.S.C. § 1."

(Link via VFX Soldier)

Tuesday, December 21, 2010

Dan Haskett Interview

The Animation Guild blog is now posting a series of audio interviews with members. The latest features old friend Dan Haskett, character designer and animator extraordinaire. (And here is part 2.) I first met Dan in New York in the 1970s, where he was one of the most prominent young bloods anxious to restore animation to the glories of the past. For those too young to remember, animation was at a real low point then. Dan has contributed to many major features and TV specials over the course of his career.

The Animation Guild blog is now posting a series of audio interviews with members. The latest features old friend Dan Haskett, character designer and animator extraordinaire. (And here is part 2.) I first met Dan in New York in the 1970s, where he was one of the most prominent young bloods anxious to restore animation to the glories of the past. For those too young to remember, animation was at a real low point then. Dan has contributed to many major features and TV specials over the course of his career.Earlier interviews are with Ruben Aquino, Bruce Smith (part 1, part 2), Ed Gombert (part 1, part 2), and Robert Alvarez (part 1, part 2). Thanks to the Guild adding labels, a quick link to all the interviews can be found here.

I really value interviews with animation artists as the mainstream media (and some recent documentaries) spend too much time focusing on management and not enough on the people who actually create the films. Now that The Animation Podcast seems to be dormant, I'm glad to see The Animation Guild taking up the slack.

Sunday, December 12, 2010

Walt & El Grupo

This is an excellent documentary chronicling the three month tour of South America by Walt Disney and assorted artists at the request of the U.S. State Department. With World War II already underway in Europe in 1941, the State Department was concerned that South America might align itself with the Axis powers, giving the Axis military bases on this side of the Atlantic Ocean. Their response, when the U.S. was still officially a neutral country, was to send cultural celebrities such as Disney (and, separately, Orson Welles) to South America to promote ties between North and South America.

This is an excellent documentary chronicling the three month tour of South America by Walt Disney and assorted artists at the request of the U.S. State Department. With World War II already underway in Europe in 1941, the State Department was concerned that South America might align itself with the Axis powers, giving the Axis military bases on this side of the Atlantic Ocean. Their response, when the U.S. was still officially a neutral country, was to send cultural celebrities such as Disney (and, separately, Orson Welles) to South America to promote ties between North and South America.This documentary, now on DVD, is written and directed by Ted Thomas, the son of Disney animator Frank Thomas who was one of the artists on the trip. Other participants included Lee and Mary Blair, Jim Bodrero, Herb Ryman, Ted Sears and Norm Ferguson. As all of the participants have passed away, the documentary relies on the memories of spouses, children and grandchildren who have often saved letters from the trip and read from them. Animation historians John Canemaker and J.B. Kaufman add their perspectives.

I have to say that I prefer this documentary to Waking Sleeping Beauty. The time period of Walt & El Grupo was a complex one, affected by both world and studio politics. In addition to the threat of war, the trip coincided with the famous strike at Disney and one incentive for Disney's participation was to get away from the studio so that less emotionally involved parties might work out a settlement. Beyond politics, the film is also good at focusing on the artists. We learn of their backgrounds and their contributions to the expedition while seeing examples of the art created during the trip. In this regard, the film is better balanced than Waking Sleeping Beauty.

Ted Thomas traveled to the places visited by the group, interviewing surviving participants or their descendants, showing newspaper clippings and movie footage of the time. The trip was well documented, both by the participants and by the local media, so Thomas has a wealth of material to work with.

The documentary does reveal that certain live action scenes of the trip used in Saludos Amigos were taken back in Burbank when the editors needed bridging material. (And if my eye doesn't deceive me, they were shot in 35mm where the actual footage was shot in 16mm.) The original release of Saludos Amigos is included as an extra. It's "original" in that it includes footage of Goofy smoking cigarettes, something deleted from later releases in order to protect children.

The film has a very large cast and if I have any criticism it's that I wish people were repeatedly identified. Seeing so many adult children of the group, it is easy to forget who they are relatives of. I also wish that more of the artwork produced on the trip was identified by artist where possible.

Walt & El Grupo does a good job of capturing a time and place in both world and Disney history. It's a pleasure to spend time with the artists and to see the magnitude of Walt Disney's popularity at the time.

Sunday, December 05, 2010

Waking Sleeping Beauty: Requiem for a Studio

Watching this film, I got the feeling that Don Hahn and Peter Schneider made it because they realized their best days were behind them and they were looking to celebrate and mourn the end of their greatest successes.

Watching this film, I got the feeling that Don Hahn and Peter Schneider made it because they realized their best days were behind them and they were looking to celebrate and mourn the end of their greatest successes.This film covers the period of Disney animation history from the change in management in 1984, when Frank Wells, Michael Eisner, Roy Disney and Jeffrey Katzenberg took over from Ron Miller until Katzenberg's resignation after The Lion King. Because the film is bookended by these two changes in management, the film gives the impression that the rise and fall of the studio during this period was due to the people at the top. While they undoubtedly had a strong influence, such as deciding which films were made, the quality of those films was determined by the literally hundreds of people who created them.

Those people are portrayed as bystanders to management politics and the film is curiously selective about who gets identified. I don't believe that Andreas Deja or Eric Goldberg, while they are shown, ever have their names on screen and (except for a deleted clip in the extras) Goldberg is not heard either. I spent a great deal of the film wondering who I was looking at or knowing and waiting in vain for the film to identify them. In an odd way, the film is like a monster movie where giant executives face off while anonymous artists run for cover. Even when the artists are identified, there is no sense of what part they played in the making of the films or their individual sensibilities.

The film is fascinating for anyone interested in animation history, but I think that overall the film is a failure. It doesn't explain why the animated features became successful except to talk about management shaking up the animation staff and the presence of Howard Ashman. There is no doubt that Ashman was a major influence in terms of the musical numbers and story construction, but he had nothing to do with the creation of the visuals. Those are left unexplained.

The film takes for granted the status of the animated features, measuring them only by box office. There's no further attempt to evaluate them in terms of quality or dissect why some were more successful than others.

The management infighting that led to the collapse of Disney animation is spelled out and no one comes off looking good. Once Frank Wells died, the remaining executive team was jealous of each other and couldn't put aside their differences for the good of the stockholders or the art form. The studio may have run out of energy anyway, but it took only seven years from The Lion King to Atlantis: The Lost Empire. For an explanation of that decline, see Dream On, Silly Dreamer.

There is one segment in the extras that shows perfectly what's missing from this film. The recording session for The Little Mermaid's song "Part of Your World" was videotaped. Inside the recording booth, Howard Ashman and Jodi Benson work on getting the interpretation right amidst the chatter from the control room. While Benson hasn't yet nailed what Ashman is looking for, her performance is superb. Her voice is beautiful and her phrasing is masterful. Music is more cinematic than animation in that it can be created in real time, but this is perhaps the only example on the DVD of the creative act, the thing at the center of the films that this documentary is supposed to be celebrating. The Disney artists were Benson's equal in their own field, though the film doesn't acknowledge this. No matter how sharp Wells, Eisner, Katzenberg, and Disney were, they were not the ones writing, directing or drawing. In this film, all the glory goes to the jockeys and too little to the horses.

It's only the popularity of the films covered in this documentary that justify its existence. Few would care to see a documentary about Hanna Barbera during the same time period. But as this film does little to explain the success of the animated features from 1984-'94, what's left is little more than a souvenir for the crew and those fans with a hunger for a look behind the scenes.

Tuesday, November 30, 2010

Kevin Parry is on a Roll

Last week, Tim Burton was in Toronto to publicize the show of his art work at the Bell Lightbox and one of the events that Burton was involved in was meeting student film makers from various local schools. Sheridan sent Kevin and his film. You can see video of the event and read Kevin's thoughts about meeting Burton here.

Canadian Animation Resources has posted the first part of a lengthy interview with Kevin about the making of his film and the next installment will cover the Tim Burton event.

Kevin is not only a good filmmaker, he's good at marketing himself. That's a powerful combination and I'm sure we'll be hearing more about Kevin in the future.

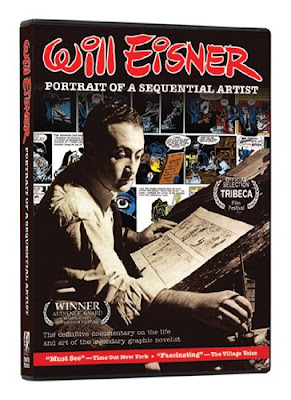

Will Eisner: Portrait of a Sequential Artist on DVD

I reviewed this documentary when I saw it in 2008 at a film festival in Toronto. The film is now available on DVD and Blu-ray. I recommend it, not only because it is an excellent film, but also due to the extras, which I'll get to below.

I reviewed this documentary when I saw it in 2008 at a film festival in Toronto. The film is now available on DVD and Blu-ray. I recommend it, not only because it is an excellent film, but also due to the extras, which I'll get to below.While Will Eisner never worked in animation, his career in comics focused on how to tell stories visually, which makes him relevant to the challenges facing animators. The documentary covers Eisner's career, which broke down into surprisingly well-defined periods. In the 1930s, Eisner was a pioneer in the comic book business, starting in the period before Superman became a massive hit. In addition to writing, drawing and editing comics, Eisner created a factory for turning out pages, a system he admitted was influenced by the Disney studio.

In 1940, Eisner was given the opportunity to create a comic book for newspaper syndication and his creation, The Spirit, provided him with a laboratory for his experiments in layout and panel breakdowns. Because he was addressing the newspaper, and not the younger comic book, audience, he pushed The Spirit into a more mature treatment of the detective genre. The Spirit was also a landmark in a business sense, as Eisner retained ownership of the strip when the standard was for a strip's creator to be employed by a distribution syndicate which held the copyright to the strip.

During World War II, Eisner was involved with using comics to teach equipment maintenance in a magazine called Army Motors. While he continued The Spirit after the war, by the early 1950s, Eisner focused exclusively on comics as a teaching tool, continuing his relationship with the military with P.S. Magazine, showing soldiers visually how to use and maintain their gear.

In the 1960s, Eisner discovered the burgeoning fandom for comics and he allowed The Spirit to be reprinted by several publishers. In the '70s, Eisner was one of the first to explore the idea of original graphic novels with his book A Contract With God. He dedicated the rest of his life to the creation of new works, including several autobiographical novels about growing up in New York and the early days of the comic book business.

The documentary covers all these periods with examples of Eisner's artwork and interviews with cartoonists who are his contemporaries and the later generations he influenced. On camera interviews include Jules Feiffer, Joe Kubert, Gil Kane, Art Spiegelman, Frank Miller, Neil Gaiman, and Scott McCloud.

Late in his career, Eisner interviewed several cartoonists for the purposes of comparing notes on how they approached their stories. These interviews were printed in various magazines devoted to Eisner's work and then collected in a book called Will Eisner's Shop Talk. Those audio interviews with artists such as Harvey Kurtzman, Jack Kirby, Gil Kane, Joe Kubert, Neal Adams and others are extras on this DVD, and for me, they alone are worth the price of the disk.

Whether you're interested in comics history, visual storytelling, or the business side of creating stories, Eisner's life and this documentary have something to offer.

Sunday, November 21, 2010

Wouldn't This Design Be More Appropriate for Woody?

Friday, November 19, 2010

Directing Animation

David Levy's books have consistent strengths. His tone is friendly and conversational. He is willing to admit mistakes he's made in his career, which gives him credibility. He interviews a wide selection of other animation professionals, so the books are not limited to Levy's own viewpoint.

David Levy's books have consistent strengths. His tone is friendly and conversational. He is willing to admit mistakes he's made in his career, which gives him credibility. He interviews a wide selection of other animation professionals, so the books are not limited to Levy's own viewpoint.His greatest strength is his concern for the people side of the animation business. Levy always focuses on behaving professionally, communicating clearly and being organized so as not to sabotage a project or one's own career.

All of these strengths are present in his latest book, Directing Animation. It includes chapters on directing indie films, commercials, TV series, features and for the web. Interview subjects include Bill Plympton, Tatiana Rosenthal, Nina Paley, Michael Sporn, PES, Xeth Feinberg, Tom Warburton, Yvette Kaplan and many others. Each of these people relate good and bad experiences they've had directing, giving a rounded view of the job and a host of things to avoid.

However, there is a hole at the center of this book in that Levy says very little about the actual craft of directing. The job of the director is to decide how the story will be told. Depending on the medium and the director, that might entail boarding, designing, cutting an animatic, directing voice talent, drawing character layouts, supervising layouts and backgrounds, timing animation, spotting music and sound effects, mixing sound and doing colour correction. Each of the above has the potential to enhance or detract from a film's effect on the audience, but you won't find any advice as to how these tasks can be used for greater or lesser results. The ultimate value of a director isn't people skills or organization, it's aesthetic. The viewers don't know (or care) if the crew got along or the production ran smoothly. Their only concern is what is on the screen.

Levy chooses not to make aesthetic distinctions. Even without getting specific about certain projects, there is still a wealth of material that could have been written about ways to communicate to an audience.

It is true that the role of the director in animation has been systematically devalued since the dawn of television. The huge amounts of footage that have to be produced for TV force directors to be little more than traffic cops, making sure that the work flows smoothly to the screen. Live action TV is dominated more by writers and producers than directors, and in animation, it's writers, designers and producers who rule the roost. Feature animation, with the exception of independent films, has mostly succumbed to the same disease. Where directors were once hired to realize their own vision, these days they're often executing another person's, lucky to insert a bit of themselves when no one is looking.

What's in this book is important and worth reading, as are Levy's other books. However, anyone interested in the craft of directing animation will find this book incomplete. The nuts and bolts of directing aren't here, let alone the distinction between what produces good and bad results.

Thursday, November 18, 2010

The Guiness Record for the Smallest Stop Motion Character

Nokia 'Dot' from Sumo Science on Vimeo.

Read more about it here.

Sunday, November 14, 2010

What's Opera, Doc?

Forget Bugs Bunny. Animation is now being used in real operas.

The use of computer animation in opera is a growing trend – it offers a broader artistic palette for set design, and for many companies it is also a savvy cost-cutting move. At the Sacramento Opera, animator Paul DiPierro, 26, is charged with supplying eight to 15 scenic projections for "Orlando."He will compose images on a digital tablet by using Adobe Photoshop and Autodesk Maya. The images will be projected on a large screen and are the equivalent of matte paintings. The images will not be animations, although animated images may be in the works for Sacramento Opera productions, DiPierro said.

"Down the line that is something that I think we will definitely be doing. The company has shown interest in using them for the 'Magic Flute.' "

DiPierro believes that the possibilities are limitless with computer-animated imagery.

"Imagine performers interacting with a fire-breathing dragon, or caught in the middle of a thundering avalanche."

Although that idea sounds far-fetched, opera companies have been doing just that, including Teatro alla Scala in Milan, Italy, which used an animated sequence of a horse moving in a fog bank for a 2006 production of "Dido and Aeneas."

Tuesday, November 09, 2010

A Toast

Last Leaf

OK Go | Myspace Music Videos

Geoff Mcfetridge used a whole lotta toast (this is at 15 frames per second) and a laser cutter to make this music video for OK Go. This is a new twist on the concept of paperless animation.

Monday, November 08, 2010

Update on The Cobbler and the Thief Documentary

Schreck successfully raised the money for the documentary through Kickstarter.com and has since gone to London, where he recorded 26 hours of interviews with people associated with the film.

Here is his latest update:

The documentary is coming along nicely. We had two terrific interviews up in Toronto back in October from two individuals who worked at the studio in the mid-1970's. At this point, I am mostly editing the project, but there may be a couple more interviews in the near future. I am currently editing the second section of the film (the production history from 1973-1983, or so). I am also trying to collect more archival material (photographs, artwork, audio or visual recordings, documents, etc.) from those who worked at the studio. What I've received so far has been fascinating and extremely informative, but if anyone else has any relevant archival material that they would be willing to share, that would be very helpful.I'm looking forward to seeing the completed work.

Sunday, November 07, 2010

The Decline and Fall of UPA

It's a cautionary tale that could apply to any animation studio, especially now that we're reaching the end of the TV era. Part 1, Part2, Part3 and Part4.

Monday, November 01, 2010

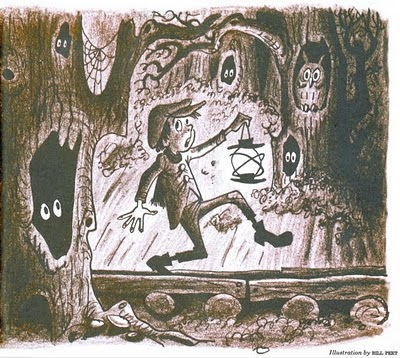

Peet, Dick, Phineas, Ferb, Nick

Ger Apeldoorn reprints some rare Bill Peet illustrations for the Mickey Mouse Club Magazine.

Ger Apeldoorn reprints some rare Bill Peet illustrations for the Mickey Mouse Club Magazine.Harvey Deneroff reports that Dick Williams completed a film he started in the 1950s called Circus Drawings and premiered it at the Pordenone Silent Film Festival in Italy.

Fast Company profiles the success of Disney's Phineas and Ferb and provides figures for licensing revenue for various children's TV properties.

The New York Times writes about Cyma Zarghami, the president of Nickelodeon, and how Nick is doing in its competition with the Disney Channel, the Hub, and Cartoon Network.

Monday, October 25, 2010

The Illusionist

I saw Sylvain Chomet's The Illusionist at the Ottawa International Animation Festival. I found it so remarkable that I returned to see it again the following night. The review below is an attempt to convey my feelings about the film without revealing too much of the story, as it has yet to be released in North America. There are many aspects of this film that I will eventually discuss in great detail, but that will have to wait until other people have the chance to see it. The film is scheduled to open in New York and Los Angeles on Christmas Day and I assume it will get a wider release early next year.

Sylvain Chomet's subject is human eccentricity. That was plain in his earlier work, The Old Lady and the Pigeons and The Triplettes of Belleville, though he hadn't found a way to combine his eccentrics with a workable story. The Illusionist, based on a script by the late French comedian and filmmaker Jacques Tati, is Chomet's best film yet, one that combines his eccentrics with a melancholy tale of age and youth.

Tati's script was written sometime in the latter 1950's, and this film has strong echoes of Chaplin's Limelight. Both films concern performers who have lost their audience and who have encounters with younger women. Limelight pairs Chaplin with a depressed ballerina. While his own career deteriorates, he helps to revive hers. In this film, Tatischeff, a stage magician, becomes the protector of Alice, a teenage maid who attaches herself to him to escape her life of drudgery.

At best, Alice is naive; she takes Tatisheff's magic as real. He works hard to fulfill her wishes. However, this puts financial pressure on Tatischeff, whose act is passé, and eventually he can no longer sustain her illusions.

What separates this film from most contemporary animated features is its acknowledgment of failure and its feeling of melancholy. Tatischeff is only one of several performers who are watching the demand for their talents vanish in the age of television and rock and roll. There is a ventriloquist, a clown, some acrobats and an opera singer, all of whom are remarkably individual in their appearance and movements. Chomet gets to indulge himself with them, but in a broader context that ties their oddness to being out of step with audiences. As this film is made with drawings in an age of cgi, I wonder if Chomet wasn't reflecting on his own situation as his animated performers became more desperate.

Live action is full of autumnal films. Limelight, John Ford's The Man Who Shot Liberty Valance, and John Huston's The Dead are suffused with sadness and a feeling of helplessness. Until now, animation has refused to acknowledge these things. As animation directors age, they don't mature or else the industry doesn't let them. Chomet is not yet 50, but he has directed this film with the wisdom and insight of someone twenty years older.

Some films become touchstones; they remain part of the conversation years after their release. For some part of the animation community, The Illusionist will be a touchstone. While I have enjoyed Toy Story 3 and How to Train Your Dragon, The Illusionist is my favorite animated feature of the year and I don't expect that will change in the remaining months.

Wednesday, October 20, 2010

NFB Open House in Montreal

Monday, October 18, 2010

When Cartoons Were Popular

Sunday, October 17, 2010

Pecos Bill Mosaic

Attending the Ottawa International Animation Festival

Dumbo Part 25

This sequence shows the aftermath of Dumbo's flying.

This sequence shows the aftermath of Dumbo's flying.The montage is a great snapshot of the public's preoccupations at the end of the 1930's. Dumbo setting an altitude record relates to the public's ongoing romance with aviation at the time. People like Charles Lindbergh, Amelia Earhart, and Wiley Post were all celebrated aviators of the period (the latter two dying in flight). "Dumbombers for defense" relates to the war in Europe, which the United States would join in 1941. The Hollywood contract had been sign of success at least since the 1910s, when performers started to make big money and in the '30s, movies and radio were the two major mass media. Dumbo's contract also explains Timothy's absence from the final scenes.

What follows the montage is the transformation of the circus. There have previously been scenes of Casey, Jr. in dark and stormy weather. He's now bedecked with flowers and chugging effortlessly in the bright sunlight. The elephant gossips are all smiles and celebrating the one they formerly ostracized. Dumbo's mother has gone from her depressing prison to a luxury car and now nothing stands in the way of her physical contact with her child. The crows have the vicarious pleasure of an outcast triumphing with their help.

The few animators credited here are effects animators, so we're completely without credits for the character animators.

Having watched this film over an extended period of time, the thing that strikes me most is how the main characters of the early Disney features are so passive and so victimized. Snow White does nothing on her own behalf except decide to become a housekeeper for the dwarfs. Pinocchio takes no positive action until he decides to save Gepetto. Dumbo's only positive action is to fly without the magic feather. Bambi goes with the flow until he fights another stag for Faline.

A character's arc implies growth towards a new viewpoint, but in the early Disney films it's like there's a binary switch that gets hit as the climax approaches. The characters don't grow towards maturity, they achieve it in an instant (and in Snow White's case, not at all). While heroes generally have mentors to guide them, in Dumbo the mentors are just about the whole show.

Dumbo's bath sequence isn't critical to the plot; it can be removed without changing the story. But it is crucial emotionally, as it is the only time we see Dumbo after his ears are revealed when he's not under attack of some sort. As a character, Dumbo is pretty much a cipher except for this sequence. There's nothing particularly individual about the way he panics when separated from his mother or the way he is scared when the elephant pyramid falls or when the clowns push him from the building.

This lack of personality, except in the most general terms, may be a reason for the film's success. Dumbo is a blank slate that the audience can write on with their own feelings of victimization. During the depression, there was no shortage of those feelings.

The recurrence of helpless heroes and savvy mentors may say something about Walt Disney himself and may mesh with the zeitgeist of the time. Walt had an older brother who looked out for him and stuck by him as he tried all sorts of questionable schemes and fell victim to a series of predatory businessmen like Charles Mintz, Pat Powers and Harry Cohen. That's practically a blueprint for Pinocchio, and Pinocchio taking responsibility for his actions may correlate to Disney taking ownership of his creations.

If Walt had Roy, America had President Franklin D. Roosevelt. In 1940, he was running for a third term, a first in American history, and he had shepherded the country through the Great Depression. The feelings of helplessness in the face of larger forces and the need for a saviour were reflected in Dumbo.

In a lot of ways, Disney and the zeitgeist separated in the post-war years. With America having won the war and become a world power, the idea of helplessness was only good for movies aimed at children. Films for adults became a lot more psychologically complex in the '50s and while there was still a lot to be afraid of (the burgeoning youth culture, the cold war and science run amok), the passivity of Disney's animated heroes was no longer mainstream. Even young Jim Hawkins gets to shoot somebody in Disney's live action Treasure Island.

Dumbo was the only Disney feature set in contemporary times until 101 Dalmatians and the only film to address racial issues until The Princess and the Frog. Racial and ethnic stereotypes show up in films like Lady and the Tramp and The Aristocats, but there is no attempt to get beyond stereotypes. If anything, the Disney films shunned present-day problems and were set in the past or in fantasy, where problems were straightforward and solutions were cut off from real-life complexity. The world of 1940 leaks into Dumbo and it's one of the things that makes the film so interesting. In several ways, the film is a precursor to Ralph Bakshi's work and it's a shame that in the intervening 30 years, neither Disney or anyone else was willing to pursue contemporary issues in the form of an animated feature.

Having completed this latest mosaic, I'd like to thank Hans Perk once again for the studio documents that make this (and the other) mosaics possible. I'd also like to thank everyone who took the time to comment.

Monday, October 11, 2010

Starz Sells Film Roman

To the best of my knowledge, this is the fifth set of owners the studio has had since it was founded by Phil Roman. The studio is best known for The Simpsons, but it works on the show as a supplier. It doesn't own any part of the show.

Starz' Toronto studio, which has produced features such as Everyone's Hero, 9 and Gnomeo and Juliet has been up for sale at least since last July.

Friday, October 08, 2010

Irish Animation

Tuesday, October 05, 2010

Jim Tyer Storyboard

Run, don't walk, over to the ASIFA Hollywood Animation Archive, where they have a complete Jim Tyer storyboard for an unproduced Terrytoon called Blood is Thicker Than Water. The material includes the script and you can see how Tyer broke it down. Some of the drawings are in blue pencil and others are finished, such as the drawing above.

Run, don't walk, over to the ASIFA Hollywood Animation Archive, where they have a complete Jim Tyer storyboard for an unproduced Terrytoon called Blood is Thicker Than Water. The material includes the script and you can see how Tyer broke it down. Some of the drawings are in blue pencil and others are finished, such as the drawing above.The writer, whoever he was, clearly had Song of the South in mind. Two of the Uncle Remus stories are referenced here, the tar baby and the "born and bred in the briar patch" sequence. The ending of the Terrytoon is forced, but Tyer's great, cartoony drawings are so much fun to look at that they make up for the story the same way his animation saved the finished cartoons.

Monday, October 04, 2010

Where Studios are Located

I've recently learned of two very interesting interactive maps. One locates computer animation studios and the other gaming studios. There may be an overlap between them.

I've recently learned of two very interesting interactive maps. One locates computer animation studios and the other gaming studios. There may be an overlap between them.There are obvious benefits to these sites for anyone trying to find a job. However, not everyone realizes the repercussions of various locations until they've experienced them.

I'm not talking about specific cities, but I am talking about studio density. Depending on where someone is in his or her career, density makes a big difference.

The problem with low density locations (i.e. with just one or two studios) is that if you get laid off or a studio closes, you have to relocate in order to continue working in the industry. This is what happened to people in Arizona when Fox closed it's studio, to people in Florida when Disney closed there, and to people in Portland when Laika laid off the crew after Coraline.

This isn't much of a problem for people who are unattached, but it becomes a much larger problem once people form romantic relationships and have children. Uprooting other people in pursuit of one's own career can create powerful resentments.

As a result, people tend to flock to those areas with half a dozen or more studios, so that if they have to change jobs, they don't have to relocate. Of course, it means that people starting their careers often have an easier time finding work in the smaller centers as it is harder to entice people to move there.

Regardless of where you might be in your career, these maps may prove useful.

Happy Birthday Buster

Today is Buster Keaton's birthday. That's him in old age next to a photo of himself as a child performer in vaudeville.

Today is Buster Keaton's birthday. That's him in old age next to a photo of himself as a child performer in vaudeville.I recently read The Fall of Buster Keaton by Joseph Neibauer, about Keaton's career after he lost his creative independence in 1928. The book is a reasonable survey of his work at Educational, Columbia, MGM and in television, but it needed a stronger editorial hand. Quotes and phrases are repeated and the book often degenerates into summaries of the films.

I'm am looking forward to reading Buster Keaton: The Persistence of Comedy by Imogen Sara Smith. The book got a very good review at Greenbriar Picture Shows.

It's amazing that 115 years after his birth and more than 80 years after his best work, Keaton continues to fascinate.

Sunday, October 03, 2010

Dumbo Part 24

Finally, Dumbo triumphs and shows his worth.

Finally, Dumbo triumphs and shows his worth.Note the large gap between shots 3 and 18. The missing shots that are on the draft are all of the clown fireman arriving and preparing to fight the fire. The Disney studio wisely decided not to delay Dumbo's triumph any more than necessary. Now that the audience knows Dumbo can fly, they are waiting to see the secret revealed and wonder how it will affect Dumbo's life.

The idea of the magic feather is frankly hokey, but it serves an important storytelling purpose. It's a convenience for the film makers, as Dumbo should not believe in the feather as he didn't have it before waking up in the tree. It's more logical to believe that Dumbo's "magic feather" should be alcohol. However, because the audience knows Dumbo can fly, there would be no suspense in this sequence without some way to cast doubt on his eventual success. As Dumbo believes in the feather and he loses it during his descent, the audience is left guessing what will happen.

The wind and siren sound effects during Dumbo's fall from the building are very effective in ramping up the suspense. Note also the airplane sound effects when Dumbo pulls out of the dive. Logically, the sound makes no sense but it is emotionally right.

Dumbo's shadow, which showed he could fly in the last sequence, is once again an important storytelling device as his shadow moves over the ringmaster and the crowd.

It's a little surprising how much Dumbo goes after the clowns compared to the elephants. The clowns were insensitive and ignorant, but the elephants knew full well what they were doing.

This sequence feels somewhat truncated. Once Dumbo takes his comic revenge on his tormentors, there's really nothing left for him to do. There's one more short sequence to wrap up a loose end, but the story is effectively over here.

The layouts for camera moves in this sequence are very effective, both during the fall and after. The moves add to the sense of urgency during the fall and afterwards bolster the gracefulness of Dumbo's flight.

The stand-out animation here is by Les Clark. His work on Timothy during Dumbo's descent is excellent and it's a shame he doesn't have more footage in the film. Grant Simmons and Ray Patterson do the clowns here, though humour comes from the clowns' humiliation, not their planned antics. Walt Kelly returns for a couple of ringmaster shots. It's a shame that some of the shots are uncredited, especially Dumbo's machine gunning the peanuts at the elephants.

Sunday, September 26, 2010

Dumbo Part 23

While there are nice bits of animation in this sequence, this section is really dominated by story and layout. The way in which the audience learns that Dumbo can fly is quite inventive. Rather than see a take-off, the screen is obscured with dust, Timothy is convinced they've failed and then the audience sees Dumbo's shadow on the farmlands below.

While there are nice bits of animation in this sequence, this section is really dominated by story and layout. The way in which the audience learns that Dumbo can fly is quite inventive. Rather than see a take-off, the screen is obscured with dust, Timothy is convinced they've failed and then the audience sees Dumbo's shadow on the farmlands below.This image is one that could only exist in a period when commercial air travel existed or the audience (and the artists) could never have conceived of such a shot.

The other great piece of layout is shot 28, where Dumbo lands on the phone wires. That's another shot that depends on the widespread use of a technology. Will future audiences understand what those wires are when all they know is cell phones? I'm assuming that Don Towsley animated the bending poles. It's a thankless task; what could be more boring? Yet the shot always gets a laugh.

Towsley's Dumbo still has a pinched face, where the features are too low on the head. Walt Kelly gets another couple of crow shots, but I've yet to see evidence, much as I admire him, that Kelly was more than a second string animator. He was right to leave the studio for greener pastures. Ward Kimball and Fred Moore get the personality shots here, but neither does work that's up to the previous sequences. The same is true for Tytla's lone shot. That's due to the story material more than their animation.

Michael Ruocco, a sharp-eyed animation student, found a series of Fred Moore drawings from a deleted scene in this sequence and shot them. Here they are:

It's shot 30, though not the entire shot. You can lip read Timothy saying, "Dumbo! I knew you could do it!" The balance of the dialogue, not in this clip, is, "Now our troubles are over. Ho-ho!" The crows apparently agree to keep Dumbo's secret in this shot (as voice over) and shots 31 and 32. The final shot of the mosaic doesn't exist on the draft, though it is very likely by Ward Kimball.

Friday, September 24, 2010

The Vault of Walt

Here's a Disney book I'm looking forward to reading. I've known Jim Korkis in print for several decades and have always enjoyed his writing and his passion for animation history. He's the co-author (with John Cawley) of several out-of-print books such as How To Create Animation, Cartoon Confidential and The Encyclopedia of Cartoon Superstars. He has contributed numerous articles to Mouse Planet under the pseudonym Wade Sampson, a name taken to avoid any conflict with his former employment at Walt Disney World (and bonus points to you if you know where the name came from).

Here's a Disney book I'm looking forward to reading. I've known Jim Korkis in print for several decades and have always enjoyed his writing and his passion for animation history. He's the co-author (with John Cawley) of several out-of-print books such as How To Create Animation, Cartoon Confidential and The Encyclopedia of Cartoon Superstars. He has contributed numerous articles to Mouse Planet under the pseudonym Wade Sampson, a name taken to avoid any conflict with his former employment at Walt Disney World (and bonus points to you if you know where the name came from).The book is over 400 pages of articles concerning Walt Disney, his films, and his theme parks. Many are based on Korkis's own conversations with Disney employees over the years in addition to historical research. For instance, I'm interested to read why the FBI opened a file concerning the original Mickey Mouse Club.

Here's a list of the book's contents:

Part One: The Walt Stories

The Miniature Worlds of Walt (Walt’s fascination with making miniatures)

Santa Walt (Walt’s feelings about Christmas and a special family gift)

Horsing Around: Walt and Polo

Walt’s School Daze (Walt’s public school education)

Gospel According to Walt (Walt’s feelings about religion)

Walt and DeMolay

Extra! Extra! Read All About It! (Walt’s adventures as a newspaper boy)

Walt’s Return to Marceline 1956

Walt’s 30th Wedding Anniversary (The very first Disneyland party)

Part Two: The Disney Film Stories

Disney’s Ham Actors: The Three Little Pigs (Including the Rarely Seen Spanish cartoon)

Snow White Christmas Premiere (Description of the event at the Carthay Circle in 1937)

Destino (The true story behind Salvador Dali’s collaboration with Walt Disney)

Song of the South Premiere (Description of the event in Atlanta in 1946)

The Alice in Wonderland That Never Was (The Aldous Huxley script never filmed)

Secret Origin of The Aristocats

So Dear To My Heart (The neglected film that inspired many Disney firsts)

Toby Tyler (How Walt recreated the circus of his youth with authentic props)

Lt. Robin Crusoe U.S.N. (Only film with a story credit for Walt Disney)

Blackbeard’s Ghost (Last live action film made while Walt was alive)

Part Three: The Disney Park Stories

Cinderella’s Golden Carrousel (The complete history of a genuine antique)

Circarama 1955 (The very first 360 degree theater show at Disneyland)

Story of Storybook Land

Liberty Street 1959 (Walt’s planned addition to Disneyland that never was)

Sleeping Beauty Castle Walk Through

Zorro at Disneyland (How Guy Williams and friends entertained in Frontierland)

Tom Sawyer Island

Epcot Fountain (The true meaning behind the popular landmark)

Captain EO (The only complete story in print about Michael Jackson’s 3-D film)

Mickey Mouse Revue (How and why the beloved attraction was created)

Part Four: The Other Worlds of Disney Stories

Khrushchev and Disneyland (Russian leader denied entrance to Disneyland)

A/K/A The Gray Seal (Walt’s favorite pulp mystery hero)

Mickey Mouse Theater of the Air (The unknown radio show from the Thirties)

Golden Oak Ranch (Location where Disney classic live action films were made)

Disney Goes To Macy’s

Tinker Bell Tales (The first Disneyland Tinker Bells and much more)

Mickey Mouse Club: FBI’s Most Wanted (Why Walt got in trouble with J. Edgar Hoover)

Chuck Jones: Four Months at Disney (Pepe Le Pew’s father’s troubles at Disney)

Walt’s Women: Two Forgotten Influences (Walt’s Housekeeper and Studio nurse)

The Disney History blog has posted an interview with Korkis about the book, which is currently available from Create Space and will be available from Amazon in early October.

Saturday, September 18, 2010

Dumbo Part 22

Except for two shots, one by Walt Kelly and the other by Don Towsley, Ward Kimball and Fred Moore dominate this sequence. Kimball does the entire song, "When I See an Elephant Fly" (except for Kelly's shot 22), including shots of Timothy. Then Moore takes Timothy over for his heartfelt recitation of Dumbo's troubles. Once again, the film is powered by contrast, this time moving from the upbeat song to the plea for understanding.

Except for two shots, one by Walt Kelly and the other by Don Towsley, Ward Kimball and Fred Moore dominate this sequence. Kimball does the entire song, "When I See an Elephant Fly" (except for Kelly's shot 22), including shots of Timothy. Then Moore takes Timothy over for his heartfelt recitation of Dumbo's troubles. Once again, the film is powered by contrast, this time moving from the upbeat song to the plea for understanding.Was Kimball ever better than this and his work in Pinocchio? The music here allows him to be as broad as he wants to be while the crows' reaction to a flying elephant is perfectly reasonable. As much as I love Kimball's work, there are times I feel his broadness pulls me out of a film. His work here and in Pinocchio has an emotional grounding that keeps him functioning as part of the story.

All of Kimball's strengths are on display here: brilliant posing, fantastic accents and eccentric movements. The bottom half of the crow with glasses in shot 12 is just astounding in the way it moves. I can't figure out how Kimball planned it. Maybe he animated it straight ahead knowing where the beats were, but there's no obvious logic to it and yet it works. The shots that follow it with the two tall crows dancing are approached more conventionally, but Kimball's posing and timing make them stand out, the same as shots 19 and 20 animated to Cliff Edwards' scat singing.

If Kimball quit the business after animating this song, we'd still consider him a genius animator.

I've already written about how Kimball doesn't care which voice comes out of which crow and also pointed out that the two crows switch positions in shot 14. I've found yet another cheat. In shots 25 and 29, Jim Crow is painted different colours, so there's a sixth crow in the sequence. This might be because the film cuts from shot 29, with all the crows on the ground, to shot 30 with Jim Crow standing elsewhere. Perhaps the wrong colours were used to avoid the appearance of a jump cut.

Moore's animation does an excellent job with Ed Brophy's voice track. His trademark rhythmic line is present in his poses and his accents, such as kicking and grabbing the hat in shot 46, are dead on. Moore captures Timothy's anguish and emotional exhaustion well, making the crows' eventual response believable. Timothy's speech provokes tears, embarrassed looks and in shot 41, a cringe when Timothy describes how they made Dumbo a clown.

I've always felt that cringe was very daring. It rips away the pretense that the crows are genuinely happy, revealing their awareness of their own social position. It's that line of dialogue and the reaction to it that convert the crows to Dumbo's allies. They know what Dumbo's experienced, even if they're not showing it. Having the crows take Dumbo's side implicitly acknowledges that they are equally victims of injustice, a rather audacious racial attitude for a 1940 Hollywood film.

Sunday, September 12, 2010

Dumbo Part 21A

The two animators whose work is important in this sequence are Ward Kimball and Don Towsley. Kimball is a master of certain things. His poses are very strong; they have a strong line of action and good negative shapes. They are also very rhythmic, with long sweeping curves that tie a character's body parts together into a unified whole. He also understands stretch and squash, changing the character's body shape to make the pose more pleasing or to communicate more effectively. As a result, the poses read very clearly.

The pose above is typical of Kimball's work. Note the negative spaces that separate the legs, arms and cigar from the rest of the body. This pose has a clear silhouette. The line that runs down the back ends at the character's right foot and the line that runs down the chest ends at the character's left toes. That line also forks and continues to the sweep of the tail. Note that the angle of the arms and the tail are parallel and that each arm is defined by continuous curved lines, broken only by scalloping to give the impression of feathers.

The pose above is typical of Kimball's work. Note the negative spaces that separate the legs, arms and cigar from the rest of the body. This pose has a clear silhouette. The line that runs down the back ends at the character's right foot and the line that runs down the chest ends at the character's left toes. That line also forks and continues to the sweep of the tail. Note that the angle of the arms and the tail are parallel and that each arm is defined by continuous curved lines, broken only by scalloping to give the impression of feathers.Kimball is also a master of contrasting timing. This was standard at the Disney studio at the time, though Kimball's background as a jazz musician may have made him more sensitive to this than most. If you watch this sequence with the sound turned off, you can clearly see how Kimball accents his animation by placing fast actions against slow ones. This is accomplished by the spacing between drawings. The wider the spacing between drawings, the faster the character will appear to move.

There's a sequence in the Disney Family Album on Kimball, where he flips key drawings drawings of Jiminy Cricket. (If you go to the link, the relevant portion is at 2:42.) Those drawings are an entire course in animation by themselves. Everything an animator has to know is in those drawings and by 1940, those qualities were as natural to Kimball as breathing.

Don DaGradi did a good job of laying out the crowd shots of the crows. However, Kimball knew how to animate them so that the audience knows where to look. This is another tough skill to master, as with 5 characters on the screen, an animator who doesn't understand staging will produce a mess of unfocused movement.

What's here is typically strong Kimball animation, but the next sequence is where Kimball really shines.

I first watched this sequence single frame on Super 8mm film. During the heyday of the home movie market, Disney released seven minute long sequences from their features in colour and sound. The last few shots of Timothy really made an impression on me due to their strong poses. At the time, I assumed that the work was by Fred Moore, though now I know it was Don Towsley, a lesser-known animator who did some excellent work at Disney.

The one negative against Towsley in this sequence is his treatment of Dumbo's face. He pushes the facial features too low on the head, giving them a pinched look.

However, his animation of Timothy is great. In those final shots, Timothy is bursting with enthusiasm for his vision of the future. Towsley puts in a lot of broad poses that are very different from each other, though each one is impeccable. As Timothy moves between the poses, the rapidity of his movements perfectly communicates his excitement at discovering the truth that will finally redeem Dumbo.

In addition to what I've already mentioned, take a close look at panels 5-12. The motion is very sophisticated in that Towsley is not having all the body parts move at once. In panels 5-9, the arms are leading the body. In panel 10, the body leads and the arm hangs back before snapping forward in panel 11 and the motion resolving itself in panel 12.

Look at how broad those poses and shape changes are. Look how appealing the drawings are. You can't tell the timing from the stills, but there's some very fast accents in that animation. Towsley really knew what he was doing.

Look at how broad those poses and shape changes are. Look how appealing the drawings are. You can't tell the timing from the stills, but there's some very fast accents in that animation. Towsley really knew what he was doing.

Monday, September 06, 2010

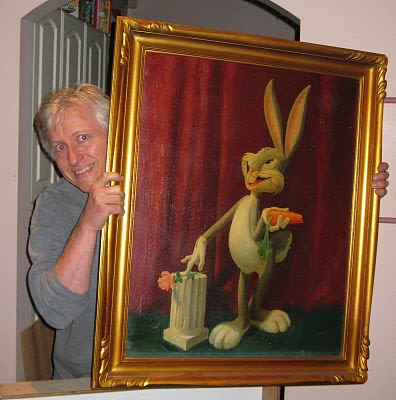

The Provenance of a Painting

Leon Schlesinger was the producer and owner of the Looney Tunes and Merrie Melodies that were released through Warner Bros. While his studio had cartoon stars like Porky Pig and Daffy Duck, Bugs Bunny surpassed both of them to become a major hit with audiences. As a result, Schlesinger had this painting made and hung in his office.

The artist is unknown, though it is likely John Didrik Johnsen, the background painter who worked in the Tex Avery unit.

Schlesinger sold out to Warner Bros. in the mid 1940s and his office contents were put out with the trash. Story man Michael Maltese was driving home and saw this painting in the garbage and took it. He kept it for the rest of his life.

Greg Duffell started at the Richard Williams studio when he was 17 years old. He was intensely interested in animation and just as intensely interested in its history. Duffell was lucky to be at the Williams studio when Williams hired veteran animators Ken Harris, Grim Natwick and Art Babbitt to work and to educate the staff.

When Duffell visited Maltese in California in the 1970s, he saw the painting in his home. Maltese passed away several years later, and his family put the painting up for auction. Duffell won the bid.

Last Saturday, I visited Greg with Thad Komorowski and Bob Jaques. We spent a pleasant afternoon talking about animation and towards the end, Greg hauled out some of the vintage animation art he's acquired over the years. When I was about to leave, Greg asked me to stay for just another few minutes while he showed one more item. He brought out the painting pictured above.

I've seen a lot of animation art but this piece had a different effect on me. Maybe because it was painted, maybe because of its size, but I think it goes deeper. I've been to museums and seen paintings by masters and while I can admire their beauty and craft, I don't have the same emotional connection to the work. Maybe it's nostalgia for my childhood or a wish to have been part of the business during the time the painting was created, but the painting was akin to a religious relic. It is an artifact from a vanished golden age, evidence of what animation once was and no longer is.

Update: Michael Barrier has printed a photo of Michael Maltese with the painting and supplied more information about the creation of the painting and how it came into Maltese's possession.

Sunday, September 05, 2010

Summer Box Office

The worry, as seen in poor results for recent 3-D releases like Cats & Dogs: The Revenge of Kitty Galore, is that theater chains and studios have overreached on pricing. “We suspect some consumers are choosing 2-D movies solely to reduce the cost of their moviegoing experience,” wrote Richard Greenfield, an analyst at the financial services company BTIG, in an Aug. 23 research note.The top grossing film for the summer of 2010 was Toy Story 3, which took in $405 million at the North American box office and grossed more than a billion dollars world-wide.

Friday, September 03, 2010

Dumbo Part 21

And so we come to the crows. Any controversy attached to this film has revolved around the crows. Some see them as a racist portrayal, others not. This blog is not going to settle the question, but I do want to look at some of the historical context. The crows, as black characters, are treated in significantly different ways than black performers in other Hollywood films of the time.

And so we come to the crows. Any controversy attached to this film has revolved around the crows. Some see them as a racist portrayal, others not. This blog is not going to settle the question, but I do want to look at some of the historical context. The crows, as black characters, are treated in significantly different ways than black performers in other Hollywood films of the time.The portrayal of blacks in film breaks down into three categories: white people in blackface, black performers who created a reputation outside of film and black performers whose careers were built on film.

Blackface, where white people would apply burnt cork to their faces and hands, is a mode of performance that dates to 19th century minstrel shows. White actors would perform songs, dances and jokes while impersonating the white perception of black people. That tradition survived into the 20th century in theatre and film with performers like Al Jolson, Eddie Cantor and, on occasion, performers like Buster Keaton, Laurel & Hardy, and Judy Garland. One of the most popular radio shows of the 1920s and '30s was Amos and Andy, focusing on a black community but voiced by white performers.

Black performers who achieved a reputation outside of film worked mostly in music. Louis Armstrong (this clip includes Martha Raye in blackface), Duke Ellington, Josephine Baker, Fats Waller, Bill Robinson, and Lena Horne appeared in films with their stage or musical personalities intact. They were brought into films to cash in on their existing reputations, usually performing on film what they performed in other media.

Black performers who worked predominantly in film were usually relegated to characters with menial jobs. Porters, butlers, maids, cooks and occasionally loyal sidekicks of the white hero. Performers like Clarence Muse, Ernest Whitman, Louise Beavers, Hattie McDaniel, Butterfly McQueen and Dooley Wilson fit this mold. Three other performers, Mantan Moreland, Willie Best and Lincoln Perry (whose stage name was Stepin Fetchit) had the same type of roles but were there to be comic relief. They played up the white stereotypes of black people; they were buffoonish, lazy and easily frightened. Black actors might get throwaway bon mots to deflate a villain or some other pompous character, but they never directly confronted a white person.

In Dumbo, the voice of the lead crow, named Jim Crow in the studio draft, is Cliff Edwards, a white performer who was previously the voice of Jiminy Cricket in Pinocchio and who had a successful career on Broadway, in vaudeville and in early talking pictures starting from the mid 1920s. The other crows were voiced by black performers from the Hall Johnson Choir, a singing group which performed black spirituals that was formed in 1925.

The crows are unquestionably meant to be the animal equivalent of black characters. Their speech patterns and eccentric wardrobes play to familiar stereotypes. However, their behaviour is something out of the ordinary. Jim Crow talks to Timothy and takes liberties (like blowing cigar smoke in his face) that would never be tolerated in a live action picture of the time. Jim Crow's whole attitude is one of superiority to the other crows and to Timothy as well. Referring to Timothy as "Brother Rat" is frankly a dig. This is one crow who doesn't know his place as defined by Hollywood in 1940. The other crows laugh at Timothy and Dumbo when they get dunked in the puddle, a demonstration of ridicule that also wasn't the norm for the time.

So while certain stereotypes are present, others are broken. However, this sequence is complicated further by the fact that Jim Crow is really white. Does that make his attitude more acceptable? Did the audience immediately know that it was Cliff Edwards? There are no voice credits on the film, though publicity photos exist of Edwards with Ward Kimball. It's not possible to know how audiences of the time interpreted the racial politics of this sequence, if they bothered at all. While it's not immediately apparent, Edwards' performance is a form of blackface.

And while there is information available about Hall Johnson himself, I've yet to find any information that named a single member of his choir other than himself. The performers who voiced the background crows are anonymous. While the choir appeared in live action films like Zenobia (with Oliver Hardy) and Tales of Manhattan, the performances that I've seen have emphasized the group, not singling out any of the singers.

How did the black back-up singers in Dumbo feel about the sequence? Did they see it as subversive? Did they resent being portrayed as crows and talking with those accents? Were they proud to tell their children and grandchildren about their participation in the film? If that information has survived, I'm not aware of it and it's a loss to our understanding of the making of the film.

There's more to say about the crows and how they function within the story, but it will have to wait for the next few sequences. I haven't even touched on the animation in this sequence, but as this has already gone on at some length, I'll do another entry on this sequence. You may be surprised to learn that my favorite animation here is by Don Towsley, not Kimball.