Profiles in History is having an auction entitled Icons of Animation on December 17. While the majority of items are out of my price range (maybe all of them actually), you can download a catalog of the auction for free.

Even if you're not in the market to buy, the catalog is a mini history lesson by itself. It contains art from Disney, MGM, Warner Bros, Fleischer and Hanna Barbera. There is work by Bill Tytla, Fred Moore, Carl Barks, Bob Clampett, Virgil Ross, Irv Wyner, Mary Blair, Preston Blair, Gustav Tenggren, Charles Schulz, etc. There are worse ways to spend time than by paging through the download and admiring so much beautiful stuff.

(link via Disney History)

Showing posts with label Bill Tytla. Show all posts

Showing posts with label Bill Tytla. Show all posts

Tuesday, November 22, 2011

Friday, May 21, 2010

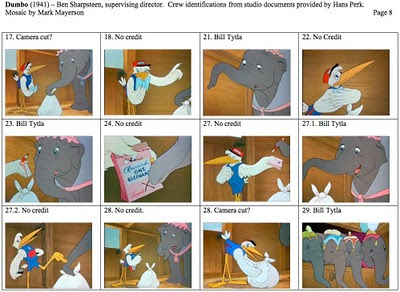

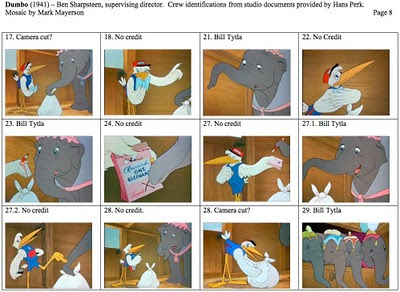

Dumbo Part 4

(Revisions down below.)

It's a shame that the Dumbo draft that Hans Perk has posted (and it's all available now on his blog) is missing many animator identifications. We can guess that Art Babbitt handled the stork in this sequence, but it remains just a guess. We're fortunate, however, in knowing what Bill Tytla animated in this sequence.

It's a shame that the Dumbo draft that Hans Perk has posted (and it's all available now on his blog) is missing many animator identifications. We can guess that Art Babbitt handled the stork in this sequence, but it remains just a guess. We're fortunate, however, in knowing what Bill Tytla animated in this sequence.

This sequence keeps the audience in suspense over Mrs. Jumbo's baby until the baby is finally revealed. It's a two stage reveal, first showing us a cute elephant child and once he sneezes, showing us the ears that are his curse and finally his blessing.

The female elephants are never named onscreen, but are named in the draft. They are Matriarch, Prissy, Catty and Giggles. They are successors to the seven dwarfs in that their names describe their personalities and that they look similar, so must be differentiated by the way they move. Needless to say, Tytla is up to the task.

No explanation is ever given as to where Jumbo, Sr. is. The lack of a male role model for Dumbo or a male counterbalance to the female gossips leaves the role open for Timothy when he later enters the film.

Revision: I think that the use of space in this sequence is very important, and my previous writing about it didn't do it justice. All space on film is constructed. Even if a film is a single shot, there's a frame around it that excludes things. Once you add cutting and camera movement, a film maker is either carving up space or implying relationships by connecting things in space.

It's a cliché, and a useful one, to start a sequence with an establishing shot, showing the audience where everything is. It would be unsurprising to follow shot 11 of the stork looking into the elephant's car with a wide shot showing how many elephants are present and what their spatial relationship is. Instead, the sequence director or the layout artist made the decision to keep the space fragmented. At screen left, we have the four elephants. In the center, we have the stork and Dumbo. On the right, we have Mrs. Jumbo. Center stage is logically where the most important action occurs, and we have the stork concerned with procedure, getting a signature, speaking his poems and singing "Happy Birthday."

Once the stork is gone, Dumbo is center stage. At this point, the left and right become two poles of a magnet. At first, they have an equal attraction for Dumbo. Both sides express obvious pride. In shot 60, Dumbo looks from his mother to the others, and is equally pleased. Interestingly, it is the matriarch, not Mrs. Jumbo, who is the first to actually touch the child. Once his ears are revealed, those on screen left radically change their view.

This results in shot 62, the only shot in the entire sequence to show all the characters at once. Mrs. Jumbo slaps one of the others and removes Dumbo to her side of the screen. For the rest of the sequence, Dumbo is always shown with his mother in the frame. The only other shot with Mrs. Jumbo and the four is 77, where she pulls the pin to shut them away.

The cutting communicates the gap between Mrs. Jumbo and the others. Dumbo begins suspended between the elephants but ends connected spatially to his mother with the four excluded from their space.

The cutting is basic. There are no bravura layouts here, but clearly a lot of thought went into how this key moment -- the revelation of Dumbo's ears and the reaction of the community to it -- was to be staged. That's typical of so much of this film. It doesn't dazzle like Pinocchio or Fantasia, but within its tight budget, the creative choices are invariably effective.

It's a shame that the Dumbo draft that Hans Perk has posted (and it's all available now on his blog) is missing many animator identifications. We can guess that Art Babbitt handled the stork in this sequence, but it remains just a guess. We're fortunate, however, in knowing what Bill Tytla animated in this sequence.

It's a shame that the Dumbo draft that Hans Perk has posted (and it's all available now on his blog) is missing many animator identifications. We can guess that Art Babbitt handled the stork in this sequence, but it remains just a guess. We're fortunate, however, in knowing what Bill Tytla animated in this sequence.This sequence keeps the audience in suspense over Mrs. Jumbo's baby until the baby is finally revealed. It's a two stage reveal, first showing us a cute elephant child and once he sneezes, showing us the ears that are his curse and finally his blessing.

The female elephants are never named onscreen, but are named in the draft. They are Matriarch, Prissy, Catty and Giggles. They are successors to the seven dwarfs in that their names describe their personalities and that they look similar, so must be differentiated by the way they move. Needless to say, Tytla is up to the task.

No explanation is ever given as to where Jumbo, Sr. is. The lack of a male role model for Dumbo or a male counterbalance to the female gossips leaves the role open for Timothy when he later enters the film.

Revision: I think that the use of space in this sequence is very important, and my previous writing about it didn't do it justice. All space on film is constructed. Even if a film is a single shot, there's a frame around it that excludes things. Once you add cutting and camera movement, a film maker is either carving up space or implying relationships by connecting things in space.

It's a cliché, and a useful one, to start a sequence with an establishing shot, showing the audience where everything is. It would be unsurprising to follow shot 11 of the stork looking into the elephant's car with a wide shot showing how many elephants are present and what their spatial relationship is. Instead, the sequence director or the layout artist made the decision to keep the space fragmented. At screen left, we have the four elephants. In the center, we have the stork and Dumbo. On the right, we have Mrs. Jumbo. Center stage is logically where the most important action occurs, and we have the stork concerned with procedure, getting a signature, speaking his poems and singing "Happy Birthday."

Once the stork is gone, Dumbo is center stage. At this point, the left and right become two poles of a magnet. At first, they have an equal attraction for Dumbo. Both sides express obvious pride. In shot 60, Dumbo looks from his mother to the others, and is equally pleased. Interestingly, it is the matriarch, not Mrs. Jumbo, who is the first to actually touch the child. Once his ears are revealed, those on screen left radically change their view.

This results in shot 62, the only shot in the entire sequence to show all the characters at once. Mrs. Jumbo slaps one of the others and removes Dumbo to her side of the screen. For the rest of the sequence, Dumbo is always shown with his mother in the frame. The only other shot with Mrs. Jumbo and the four is 77, where she pulls the pin to shut them away.

The cutting communicates the gap between Mrs. Jumbo and the others. Dumbo begins suspended between the elephants but ends connected spatially to his mother with the four excluded from their space.

The cutting is basic. There are no bravura layouts here, but clearly a lot of thought went into how this key moment -- the revelation of Dumbo's ears and the reaction of the community to it -- was to be staged. That's typical of so much of this film. It doesn't dazzle like Pinocchio or Fantasia, but within its tight budget, the creative choices are invariably effective.

Sunday, April 01, 2007

Pinocchio Part 5A

As the spectre pointed out in comments to Part 5, it's likely that the draft is wrong in crediting Ham Luske for any Cleo animation. When I saw the spelling change from "Luske" to "Lusk," I realized that it was far more likely that Don Lusk was animating Cleo rather than someone as important as Ham Luske working on a relatively insignificant character.

There is another error in the draft. Between 61.1 and 63.3 in the mosaic, there's a 4 second shot on the draft labeled 61.4 with animation by Johnston, Bradbury, Karp and De Beeson that's described as "MLS - Pinocchio and Figaro dancing. Pino sees candle burning. (Geppetto singing off stage.)" No question that shot was animated, but it ended up on the cutting room floor.

For all of this film's elaborateness, there are some cheats. It's standard for animation that's over a panning background to be done on ones. In scene 11, some strange things are happening. It could be the DVD transfer, but it appears that every 5th frame of the panning background is on 2's. The animation is all on two's, but on every fifth frame it's on 3's! Even if the DVD transfer is guilty of causing this, there's no question that the animation is on 2's while the background pans on 1's.

We know about Tytla's Stromboli, but here he handles a lot of Geppetto. He probably has the most sustained acting in this sequence and does a great job with it. While some feel that Stromboli is over-animated, Tytla's Geppetto is a very clear and direct performance. Tytla handles Geppetto's fear and surprise well in addition to Geppetto's pleasure at discovering Pinocchio is alive. This sequence is exactly the kind of thing that allows Tytla to do his best work. The acting is grounded in strong emotions and the shifting emotions give Tytla the chance to show off his range as an actor. Stromboli and Chernobog are more bravura performances, but there's an honesty to Tytla's Geppetto that makes it closer to his work on Dumbo and personally I prefer it.

The most noticeable thing about this long sequence is how many different people had a hand in it. It's got a wide assortment of animators on every character. Other Geppetto animators in this sequence include Walt Kelly, Fred Moore, Bill Shull and Art Babbitt. Pinocchio gets handled by Ollie Johnston, Milt Kahl (his Pinocchios in this sequence cuter than in the last), Frank Thomas, Marvin Woodward, Phil Duncan, Bob Youngquist, Les Clark and Harvey Toombs. The rest of the characters fall into the same pattern. As a result, it's difficult to talk about performances because few animators besides Tytla got more than a few shots in a row for their characters.

At the end of this sequence, we're finished with the first act of the film. Except for a brief time after the credits, we've stayed inside Geppetto's house and all our time getting to know the film's protagonists. This film builds more slowly than more recent animated features, which usually start out with an action sequence rather than risk boring the audience. There's been lots of comedy and three musical numbers already, but the first act has been all about meeting the characters, setting up their relationships and establishing what Pinocchio needs to do to become a real boy.

From this point forward, the film moves out of Geppetto's house and into the wider world. The second act is all about how the protagonists fail each other.

There is another error in the draft. Between 61.1 and 63.3 in the mosaic, there's a 4 second shot on the draft labeled 61.4 with animation by Johnston, Bradbury, Karp and De Beeson that's described as "MLS - Pinocchio and Figaro dancing. Pino sees candle burning. (Geppetto singing off stage.)" No question that shot was animated, but it ended up on the cutting room floor.

For all of this film's elaborateness, there are some cheats. It's standard for animation that's over a panning background to be done on ones. In scene 11, some strange things are happening. It could be the DVD transfer, but it appears that every 5th frame of the panning background is on 2's. The animation is all on two's, but on every fifth frame it's on 3's! Even if the DVD transfer is guilty of causing this, there's no question that the animation is on 2's while the background pans on 1's.

We know about Tytla's Stromboli, but here he handles a lot of Geppetto. He probably has the most sustained acting in this sequence and does a great job with it. While some feel that Stromboli is over-animated, Tytla's Geppetto is a very clear and direct performance. Tytla handles Geppetto's fear and surprise well in addition to Geppetto's pleasure at discovering Pinocchio is alive. This sequence is exactly the kind of thing that allows Tytla to do his best work. The acting is grounded in strong emotions and the shifting emotions give Tytla the chance to show off his range as an actor. Stromboli and Chernobog are more bravura performances, but there's an honesty to Tytla's Geppetto that makes it closer to his work on Dumbo and personally I prefer it.

The most noticeable thing about this long sequence is how many different people had a hand in it. It's got a wide assortment of animators on every character. Other Geppetto animators in this sequence include Walt Kelly, Fred Moore, Bill Shull and Art Babbitt. Pinocchio gets handled by Ollie Johnston, Milt Kahl (his Pinocchios in this sequence cuter than in the last), Frank Thomas, Marvin Woodward, Phil Duncan, Bob Youngquist, Les Clark and Harvey Toombs. The rest of the characters fall into the same pattern. As a result, it's difficult to talk about performances because few animators besides Tytla got more than a few shots in a row for their characters.

At the end of this sequence, we're finished with the first act of the film. Except for a brief time after the credits, we've stayed inside Geppetto's house and all our time getting to know the film's protagonists. This film builds more slowly than more recent animated features, which usually start out with an action sequence rather than risk boring the audience. There's been lots of comedy and three musical numbers already, but the first act has been all about meeting the characters, setting up their relationships and establishing what Pinocchio needs to do to become a real boy.

From this point forward, the film moves out of Geppetto's house and into the wider world. The second act is all about how the protagonists fail each other.

Thursday, May 04, 2006

Fred Moore and Bill Tytla

Both these animators were hugely influential at Disney in the 1930's and both left the studio in the 1940's. Moore returned after putting in time with George Pal and Walter Lantz, but Tytla never returned. He went to Terrytoons as an animator and later moved to Famous Studios as a director.

What interests me is the difference in their experiences and reputations after leaving Disney as I think it illuminates something about their work.

Moore is famous for the appeal of his drawings and he maintained that appeal when his drawings moved. While he is associated with specific characters in the early Disney features (Dopey in Snow White, Timothy in Dumbo and Lampwick in Pinocchio), I think that his sense of design dominated his ability as an actor.

When Moore went to Lantz, his work remained recognizeable and continued to be appealing, even when animating characters as bland and formula as Andy Panda or the dwarf rip-offs in Pixie Picnic. While Moore was probably forced to work faster than he did at Disney, his work really doesn't seem to suffer much.

When I first read Disney Animation: The Illusion of Life, I resented how Thomas and Johnston treated Moore. In the intervening years, though, I think that I've come around to their point of view. When they talk about Moore not being able to keep up, I think it's a criticism of his acting. Moore was enormously talented, but his talent was a surface one. For whatever reason, he didn't get as deeply into his characters as other Disney animators were beginning to do.

By contrast, I think that Tytla's main skill was his acting. He was classically trained as an artist, so he was certainly no slouch in terms of his drawing skills. His Grumpy is really the only character in Snow White that undergoes a significant change over the course of the film and is the greatest acting challenge because of that. The emotional relationship Tytla was able to evoke between Dumbo and his mother is stronger than anything else in that film and would rarely be rivaled in later Disney features.

Leaving Disney, Tytla became a great actor in search of a great part. The kind of drama that he excelled at wasn't being done anywhere besides Disney. Whatever one's opinion of Terrytoons or Famous Studios, can anyone point to a genuinely great performance that came out of either one? It's not that those studios tried and failed, it's that they never conceived their films in terms of Tytla's strengths in the first place.

While Moore could conjure a great drawing out of nothing, Tytla couldn't create a great performance without a well thought out story, character and voice track to fuel his animation. Tytla needed a kind of support that no studio besides Disney was capable of providing. That's why Tytla's career was effectively over when he left Disney and Moore's was able to continue without suffering nearly so much.

What interests me is the difference in their experiences and reputations after leaving Disney as I think it illuminates something about their work.

Moore is famous for the appeal of his drawings and he maintained that appeal when his drawings moved. While he is associated with specific characters in the early Disney features (Dopey in Snow White, Timothy in Dumbo and Lampwick in Pinocchio), I think that his sense of design dominated his ability as an actor.

When Moore went to Lantz, his work remained recognizeable and continued to be appealing, even when animating characters as bland and formula as Andy Panda or the dwarf rip-offs in Pixie Picnic. While Moore was probably forced to work faster than he did at Disney, his work really doesn't seem to suffer much.

When I first read Disney Animation: The Illusion of Life, I resented how Thomas and Johnston treated Moore. In the intervening years, though, I think that I've come around to their point of view. When they talk about Moore not being able to keep up, I think it's a criticism of his acting. Moore was enormously talented, but his talent was a surface one. For whatever reason, he didn't get as deeply into his characters as other Disney animators were beginning to do.

By contrast, I think that Tytla's main skill was his acting. He was classically trained as an artist, so he was certainly no slouch in terms of his drawing skills. His Grumpy is really the only character in Snow White that undergoes a significant change over the course of the film and is the greatest acting challenge because of that. The emotional relationship Tytla was able to evoke between Dumbo and his mother is stronger than anything else in that film and would rarely be rivaled in later Disney features.

Leaving Disney, Tytla became a great actor in search of a great part. The kind of drama that he excelled at wasn't being done anywhere besides Disney. Whatever one's opinion of Terrytoons or Famous Studios, can anyone point to a genuinely great performance that came out of either one? It's not that those studios tried and failed, it's that they never conceived their films in terms of Tytla's strengths in the first place.

While Moore could conjure a great drawing out of nothing, Tytla couldn't create a great performance without a well thought out story, character and voice track to fuel his animation. Tytla needed a kind of support that no studio besides Disney was capable of providing. That's why Tytla's career was effectively over when he left Disney and Moore's was able to continue without suffering nearly so much.

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)