This sequence introduces Lampwick, sort of the anti-Jiminy. His anticipation of the fun on Pleasure Island, contrasted to the Coachman's reaction shot (9.1) sets up the two sides of the island that we'll get to see.

While you couldn't know it until seeing the film a second time, the coach is drawn by donkeys, undoubtedly ones who were previously passengers.

Once again, Pinocchio is a blank slate, not recognizing that the ace of spades isn't a ticket, though it generally is a symbol of death. Lampwick's personality overpowers Pinocchio, not letting him finish a sentence. Lampwick indulges himself by shooting rocks at the donkeys. For all of his bravado, he proves to be as gullible as Pinocchio about what awaits them. If he only knew where those donkeys came from...

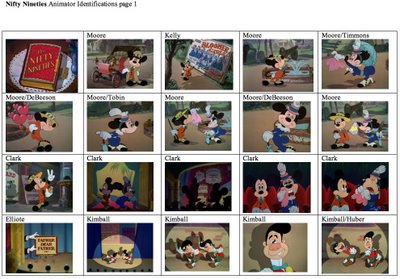

Fred Moore is the star here. In just a few shots, he defines Lampwick as a type: the boy who thinks he's tough and who can't wait to grow up to be a "hoodlum" as Jiminy will call him. The appealing design is necessary. We've got to like Lampwick enough so that when his transformation occurs, it horrifies us. If he is a unlikable character, we might cheer his punishment, so Moore has to walk the line between attracting and repelling us with the character and he strikes the right balance.

Note shots 3 and 9 for the coach passengers. They are simplified, probably due to the size they were drawn. This problem plagues the Fleischer version of

Gulliver's Travels quite a bit during the sequence where Gulliver is bound by the Lilliputians. It's a bit surprising to see it in this film, even for only a few shots.

There are some nice effects shots as the coach reaches the shore, the boys board the ship and the ship sails to the island. Shot 18 uses a held painting of the boat and water effects that are panned towards the opening in the rocks. The shot is simple compared to much in the film, but it shows how good art direction and a strong composition can often do a better job than elaborate effects.

Addendum to Part 13A: There's been discussion about Shamus Culhane's animation of Honest John and whether or not he was unfairly deprived of credit. I have no more information on that, but on page 145 of

The Animated Man: A Life of Walt Disney by Michael Barrier, Hugh Fraser is quoted as to how he did 48 pencil tests of sequence 7, shot 30. Culhane claimed to have worked on sequence 7, where Honest John and Gideon plot with the coachman, and while Fraser's scene was probably an extreme case, it's possible that Culhane's scenes were also revised numerous times after he left by Norm Tate, leaving little or nothing of Culhane's work. T. Hee was the sequence director of sequences 3 and 7, both of which Culhane claimed to have worked on, so Hee may be more responsible than Walt Disney for Culhane not getting credit in the drafts or on the film.