Today is Ray Harryhausen's 90th birthday. In his honor, let's all duel with skeletons.

Reflections on the art and business of animation.

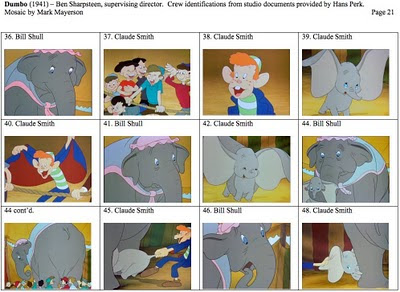

Another frustrating entry, due to the lack of credits in the second half.

Another frustrating entry, due to the lack of credits in the second half. I've read a fair number of business books about the film industry and this is a good one. Author Nicole Laporte does an excellent job of portraying the three partners, Steven Spielberg, Jeffrey Katzenberg and David Geffen, who formed DreamWorks.

I've read a fair number of business books about the film industry and this is a good one. Author Nicole Laporte does an excellent job of portraying the three partners, Steven Spielberg, Jeffrey Katzenberg and David Geffen, who formed DreamWorks.

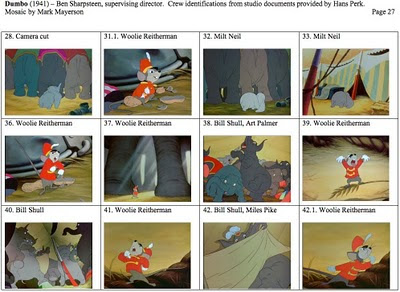

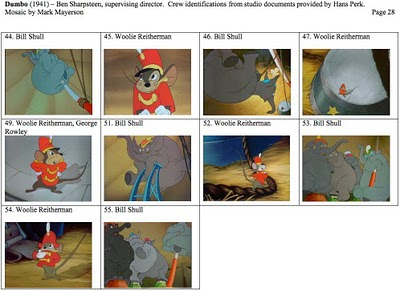

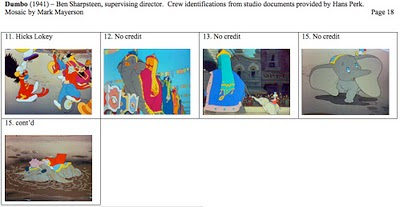

This really is Woolie Reitherman's section. He animates practically everything. Ed Brophy, the voice of Timothy, gives an excellent reading, alternating between coaxing, thinking out loud, cheerleading and puzzlement. Reitherman catches all those emotions in his animation. Between Brophy and Reitherman, we get a good understanding of Timothy, a character who is warm-hearted, considerate and intelligent.

This really is Woolie Reitherman's section. He animates practically everything. Ed Brophy, the voice of Timothy, gives an excellent reading, alternating between coaxing, thinking out loud, cheerleading and puzzlement. Reitherman catches all those emotions in his animation. Between Brophy and Reitherman, we get a good understanding of Timothy, a character who is warm-hearted, considerate and intelligent.

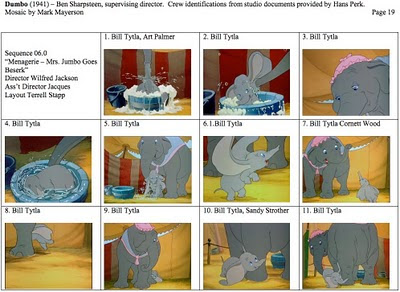

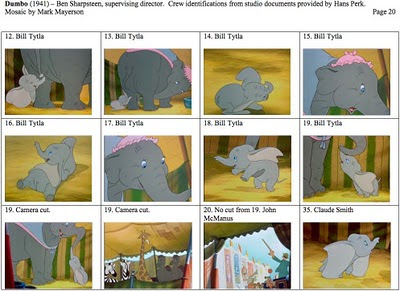

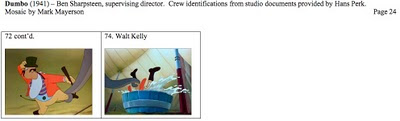

This sequence begins with Mrs. Jumbo and Dumbo both sadly swaying to the music. Though separated by space, their mirror actions show that their feelings are the same; they are depressed due to their separation.

This sequence begins with Mrs. Jumbo and Dumbo both sadly swaying to the music. Though separated by space, their mirror actions show that their feelings are the same; they are depressed due to their separation.

"I hate the term “2D.” That’s bullshit. They put us in that category. They say they’re making 3D. They’re not 3D. What Pixar does is not 3D because it’s shaded. The screen is flat. It’s a flat picture. It’s just an illusion. There’s only one 3D, Brian, and that’s what you’re looking at with your two eyes. You are seeing real space. It’s all around you. And you can touch the objects and see that they’re really there."The four part Gene Deitch interview is now complete. Go here for links to all four parts.

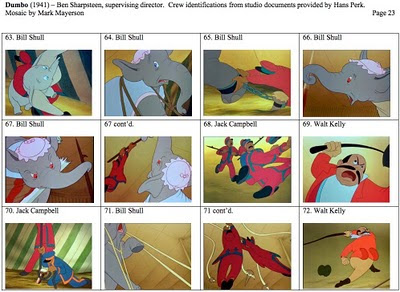

Once again, the principle of contrast is front and center here. The first half of the sequence is relaxed and heartwarming while the later half is tense and frightening.

Once again, the principle of contrast is front and center here. The first half of the sequence is relaxed and heartwarming while the later half is tense and frightening.

As I watch this film in chunks, I am struck by how much the film relies on contrast. Each sequence seems to contrast with the last and there is contrast within sequences as well. This sequence follows the raising of the big top during a thunderstorm. Where the previous sequence was dark and grey, this one is bright and colorful. The music here also contrasts with the roustabout song.

As I watch this film in chunks, I am struck by how much the film relies on contrast. Each sequence seems to contrast with the last and there is contrast within sequences as well. This sequence follows the raising of the big top during a thunderstorm. Where the previous sequence was dark and grey, this one is bright and colorful. The music here also contrasts with the roustabout song.